Human Rights: Speech by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the 25th EU-NGO Forum for Human Rights

Good afternoon,

I think it was one American Secretary of State who said: “I would like to talk to the European Union, but I do not know which phone number to call”. It is still not clear which phone number you have to call when you want to talk to the European Union. The European Union is a complex club of Member States – more than a club. It is a gathering of Member States which have decided to put together some of their sovereignties – the monetary one is the clearest one, with the [European] Central Bank, and others. And to keep for them other parts of their sovereignty, in particular, foreign policy and defence policy, which are clearly state-owned competences.

Read also

But at the same time, they decided to try to build a common foreign policy and a common security policy. But as you can understand, common does not mean unique. I share something with you, but we do not share other things, which is the communality. This is a difficult thing to answer. In some cases, there is a clear position and in others, there as many positions as Member States. Look at the last vote of the United Nations General Assembly about the Arab countries’ initiative with respect to the truce or the ceasefire, or whatever you want to call it, in Gaza. Four voted against eight voted in favour and 14 abstained. A clear example that there is not a common position. When there is not a common position, each one keeps its own position and I, “as spokesperson for the common position”, there is not a lot to say because there is not such a common position.

The important thing is not to announce the common policy or the common position, but to try to build it. To try to put people together, to see why there are different visions and how we can overcome these visions in order to have a common position.

Sometimes, it is not possible, the differences are very big. Other [times], there is a natural understanding in common positions.

The same happens with the monetary policy. Today, everybody knows that the members of the Eurozone share a common currency. A common and unique, because they do not have [an]other. But for many years, we had a common currency which was called ECU [European Currency Unit], but it is not unique, and we had at the same time our national currency – in Spain, we had the Peseta, in France, they had the Franc – and we shared a common currency, which was not unique. But how do you manage to have each one their own currency, and at the same time to share a common one?

Well, with a complex system of equivalences, maybe some of you remember the snake in the tunnel, meaning that there were going to be some oscillations with respect to the central value of the common currency, but this oscillation should not overpass a certain limit. There was a tunnel and a snake, showing that each currency has to keep a certain value with respect to the common, the ECU.

More or less, we are trying to do the same thing. With the difference that the tunnel is very wide and the positions [are] diverse in some cases, because some say yes, and others say no.

This is the way we work, and then you have the complex institutional settings.

We have a Commission which is the executive power for the competences that have been communalised, not for the others.

We have a Council that is the real master of the European Union because it is the Member States who gather together in order to fix guidelines that, then, we try to implement.

In this complex environment, in a complex world, it is becoming more and more difficult to fix a position which can be implementable, not just in a matter of principles but in actions.

This introduction is to give an answer to who is speaking on behalf of the European Union, but in depends on what. I can even say, it depends [on] when. It depends also on the permanent fight, in the political sense of the word, between these complex institutional settings, which are the competences of the Member States, and which are the competences of the [European] Commission. It is defined in the treaties, but as any legal definition there are overlaps, and there is the critical political pressure from one side and the other to have the lead.

This is especially true when we talk about the more political things, the more this institutional controversy sometimes appears.

Then, there is the [European] Parliament – do not forget about the Parliament – which is the co-legislator for many things, not for all [of them] but for many, and who is the co-budgetary authority. The budget has to be approved by the Parliament, and by the Council [of the European Union]. Both have to agree.

What happens when they disagree? Well, then there are discussions, the [European] Commission intervenes, but the decision is not for the Commission, the decision is [for] the Council and the Parliament, the two co-legislators.

Sometimes, the Parliament has a view, and the Council has another view. Member States divert, they differ. And I receive criticism from both sides; from the side of the Parliament, from the side of the Member States; so, this is a difficult job. But it is more and more difficult because the world is more and more complicated.

When I came here, 4 years ago things were much easier, but since then, we had a pandemic, and we had two wars. The war of [aggression of] Russia against Ukraine, and the current war – or the conflict – between [Hamas] and Israel. But many others.

And human rights have been more and more violated, and I cannot say the world is driving to a future based on peace and cooperation. The contrary, I see more and more human rights abuses, and less and less cooperation.

At the institutions, for example, you see for example the [United Nations] Security Council [where] there are more and more vetoes, and less and less agreements.

Then, it has to go the United Nations General Assembly, where there is no veto, but the majority, but without executive capacity. Although the executive capacity decision of the Security Council is also quite theoretical because there are a lot of resolutions which have been voted, agreed, but not implemented. The last one is the request for a ceasefire in Gaza which has been voted at the Security Council , General Assembly, but not implemented.

All [of] that is in the middle of a big world turmoil, and the 75th anniversary of the [Universal Declaration] of Human Rights, 25 years of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders and the Rome Statute, and the 30th anniversary of the Vienna Declaration.

In order to celebrate that, the other day I bought a book, which is a practical guide to humanitarian law. Because we talk about humanitarian law, we talk about the respect of international law, including humanitarian law. We talk about it a lot, but to tell the truth, every time I ask for legal advice about how the humanitarian law is being implemented, I have so [many] different views that I decided to buy a book A practical guide to humanitarian law in order to be able to understand which is the content of these human rights defenders declarations, the Rome Statute, which is the role of International Criminal Court, how does it work.

[With] so many conflicts around the world, what is a war crime and who has to decide if something is a war crime, the legal sense of the world? Where do human rights start? Who is violating them? Who are defending them?

This is part of my portfolio. We have here our Special Representative for Human Rights [Eamon Gilmore] and we have a lot of resources devoted to defend human rights and to defend the defenders of human rights.

The difficulties of the time in which we are living should only encourage us to continue defending human rights globally. Because what we are seeing is the return of brutal power politics. More and more conflicts are being solved by the use of force. Something that was supposed to be forbidden. Not the use of force to solve conflicts, but what I see is that there are more and more conflicts [are] being solved by force.

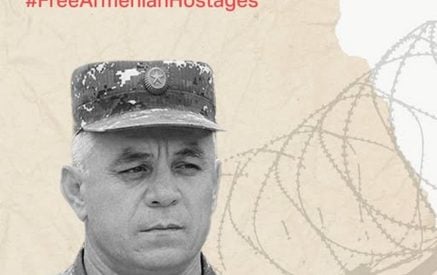

Look for example at what has happened in Azerbaijan and Armenia. A long-frozen conflict that suddenly has been – I would not say solved – but decisively determined by a military intervention that, in one week, made 150,000 people move. In one week. Like this. 150,000 people had to abandon their houses and run. And the international community regretted [it], expressed concern, sent humanitarian support, but it happened [with] the use of force.

This is a more recent example but look at what has happened in Sudan, in Ethiopia, what happened in the Sahel, [and] what is still happening in many Latin America countries where violence increases. I remember Costa Rica was supposed to be the Switzerland of Latin America. When you have a look at the numbers of criminal acts happening in Costa Rica twenty years ago and today, it is skyrocketing.

Drugs have a lot of things to do with that. Many countries around the world have been destabilised by the fact that drug dealers are so powerful.

I made a phone call – I am going out of my paper – to the new recently elected President of Ecuador [Daniel Noboa] – recalling that the candidate of his political party was killed – assassinated – during the campaign – and he told me: “Do you know how many tons of drugs are being exported from Ecuador?” In estimation certainly, because there is no record, obviously; 2,000 tons.

Do you know how much it cost a ton of drug in Europe? Between €50 and €100 million. Multiply that. It makes the amount of cash generated by the drug traffic, two times the GDP of the country. Someone has in cash two times the GDP of the country. How do you fight against it? How do you ensure the rule of law? How do you ensure that this money is not being used to corrupt anyone? From the humblest policemen or policewomen to the highest ranks of the political structure. Yes, drugs are something that are rooted in the political structure of many countries around the world. In particular, in concrete this part of the world, South America, but also in Africa.

So, yes, we see a regression of human rights. We see increasing violence and increasing inequality. We see disinformation. [Pay attention to] the images that you see on the social [media], verify them before wide spreading because maybe they are false. I see in my case some moments in which I said: “Look at that!” and five minutes later my team said: “This is not what you think it is.”

The image is real but did not happen there. It [didn’t] happen yesterday; it happened somewhere else many years ago. They [could] be widespread and people [could] believe it. How do we fight against this wave of disinformation with information?

Democracy is a system that works with information. Information is the engine of democracy. People are being called to choose. But when you make a choice, it is because you know the properties of the options. You have to be able to make a judgement. And your judgements are [made] on your perception, which is always particular and maybe not significant, and on the reality of things. One of the biggest problems that we have today is the wave of disinformation, and people presenting bad solutions to real problems, what we call “populism” and “extremism”.

All that, with some structural problems that everybody is talking about, like climate change. Everybody is in the Gulf today, talking about climate change problems. This is a security problem: climate [change] creates insecurity. [It] is creating migration, people on the move. If you cannot cultivate your piece of land, you will have to leave. That is what is happening in some parts of the world. Migration has been pushed by climate [change] [and] the fight for natural resources.

Climate has become an existential threat and not for tomorrow, it is right now. But certainly, tomorrow it will still be worse.

Unhappily, human rights and international law are always the first casualties or worse of military coups. Since I am here in Brussels, I do not know how many military coups I have witnessed. In some parts of the world, it is a domino effect. One country starts and then the others follow. I am thinking [about] the Sahel area, which is leaking to the Gulf of Guinea.

Who remembers what has been happening in Kabul? Afghanistan has disappeared from the media. In Afghanistan, you have a “gender apartheid”. I think this is a good way of calling what is happening there: a “gender apartheid”. Not by the colour of the skin, but by gender. Woman and girls are deprived from going to the schools, and an awful dictatorship is ruling the country.

What is happening in Tigray? Hundreds of thousands of people have died in the civil wars inside Ethiopia. First with the Tigray [one], after with the Amhara [one].

What is happening in Sudan? Where at least three warlords are fighting against each other just to try to keep [the] power. Each one of them is supported by some of the neighbours. One neighbour supports one, the other neighbour supports the other.

Do you remember Darfur? The awful crisis in Darfur is coming back. There are hundreds of thousands of people, refugees, fleeing from the Sudan war going to neighbouring Chad or Ethiopia.

Look at what is happening in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where we tried to send an Electoral Observation Mission. In fact, they were there, and we had to withdraw this mission because the conditions were not met in order to deploy these people in a meaningful way.

They were there, more than 50 members, some of them members of the European Parliament. And unhappily, had to withdraw because the conditions to hold this observation mission were not met.

Or [what is happening] in Myanmar, or in Syria.

Today, the terrible development that continue unfolding in Israel and Palestine have started with this terrorist attack that killed 1,200 people, 200 hostages. Certainly, an act of terror against civilians, defenseless.

And then we have witnessed – well, this was a carnage – what we are witnessing in Gaza is another carnage. How many victims? We do not know. Nobody knows. Someone’s estimate is about 15,000, but I’m afraid that below the rubble of the houses destroyed there must be many more. With a high number of children.

People are leaving the room? Maybe I said some inconvenience, but the United Nations has clearly said that what happened in one case was a carnage and what is happening in Gaza is another one.

Because one cannot accept this high number of civilian casualties even [if], obviously, Israel has [the right to] defend itself. As I said, one horror cannot justify another. There was a horror, but one horror cannot justify another. International communities, more and more, are raising their voices asking for this horror to stop. I travelled to the region. I met with the Israeli and the Palestinian leadership and many other regional actors. On that, we have a concrete agenda. We are asking for the [release] of all hostages, to put an end to this man-made humanitarian catastrophe, to look for a solution for the day after, stop the illegal [Israeli] settlements and the aggressions against Palestinians in the West Bank. When the Oslo Agreements were signed 30 years ago, there were four time less settlers in the West Bank than today, which makes the two-state solution much more difficult.

To avoid the spillover of this conflict in the region – which is becoming more and more difficult too – to, because you see the Houthis launching rockets against Israel and affect the freedom of navigation in the Gulf.

To combat antisemitism, also islamophobia, and Palestino-phobia in Europe and elsewhere. I think one has the right to [criticise] the state of Israel, the government of the state of Israel, without being qualified as [antisemitic]. I can disagree on how a government behaves without being qualified [as] “anti” something.

I can criticise the Franco government in my country, when it was a dictatorship, without being anti-Spanish. I can disagree on what is happening in some places without being “anti-this place”.

In particular, I ask for the right to defend a two-states solution without being against the existence of the State of Israel.

We have to continue working for the regional and international partners to look for a political solution. It can be this two-states solution, but the debate is open. [If] someone has other solutions, please, let us discuss about it. Because either there are two states; there is one state, either there is no states at all.

I would not like Gaza to become a new Mogadishu, or a place without law and order which could be the cradle for all kind of violence and terrorist movement, and irregular migration.

All that is very complicated, and I think that we have to go to the essential. The essential is that we need a rule-based order. We need rules, because without rules, the ones who suffer [the most] are the [most vulnerable] people. La loi protège, la loi n’opprime pas, la loi protège. C’est l’absence de loi qui opprime. When there is no law, when there is no freedom, when there is no protection of the most vulnerable, then it is the worst possible situation. This is why we have to stand everywhere, every time, in front of everybody for international law and United Nations Declaration for Human Rights – be it in Ukraine, in Israel, in Gaza, in Ethiopia, in Sudan, in the Sahel, in Belarus, Syria or Myanmar.

And I think we also have to avoid that all these conflicts converge [in] a greater conflict. We have to avoid what someone called “the West against the rest”, which is a minimalist way of looking at the world. The West. The West covers from Alaska to Japan. So, it is not exactly… what is the West? The West is not a geographical denomination. The West is a group of people that share some political and economic organisations. And the rest, what is the rest? The rest is too heterogenous to be considered as a political actor.

There are the BRICs, there are the Global South [countries], different multipolarities, that sometimes converge in this clash of civilisations that we try to avoid. Now, I am afraid it is coming – it is coming back again.

So, I ask all of you to do your best in order to avoid a global clash, and to try to face each one of the challenges we are facing [in] its own circumstances – I will not say merit, because there is no merit but specific situation.

Keep the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a groundbreaking document, the basis of everything that has to deal with the equal dignity and equal rights for every human being – which it is easy to say, and very difficult to make a reality for everyone.

That is why it is good that we stand here. It is at the basis of many objectives of the European Union around the world.

In particular, the European Union is very much engaged in fighting against gender inequality. We are very much engaged against violence against women and girls, because the figures are really shocking. Globally, it is said that about 1 out of 3 women have experienced some form of physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner or by a former partner.

They are not victims of a war, but in the hands of someone that they have never met before. It is their partners and sometimes, they are intimate partners.

We try to support the fight against violence against women, but it is rooted in structural inequalities in our societies. It is not something that happens [for] cultural reasons, it is a structural issue which has deep roots. All of us have a responsibility to address it.

In order to fight against these problems, three years ago we established the Global Human Rights Sanction Regime as an essential tool. And I would like to extend this regime [with] another listing of the next Foreign Affairs Ministers [meeting]. We, almost every meeting, come with a list of people that has to be sanctioned under this sanction regime. It is one of our tools. It is certainly not enough. But it is what we can do. And at the next Foreign Affairs Council we will discuss another package affecting people that some years ago was not imaginable that this could happen.

It is also important that the young people remain engaged in that. We try also to support the young people engaged in defending human rights. I am not going to explain all [of] what we do, I am sure someone has explained [it to] you before. But I think that we have to pay special attention to defend the defenders – to defend the defenders of human rights – because they are often the first victims of the activities. They take great personal risks. Last year, I remember some activists that were killed in Honduras, but I can say so [about] many people around the world. The numbers [are] already shocking.

We have been helping about 4,000 human rights defenders [who] are at risk. We have a concrete mechanism to support them: our Protect Defenders Mechanism. And I know this is a drop of water in the ocean because our financial resources are limited. And I might say [tell] you that we allocated €500 million to fight against violence against women globally. I know this is certainly not going to solve the problem. But it may help and, in particular, this can be the seed in order for many people to engage on this file.

I have to thank you, because I am sure you are strongly engaged in that, and you represent a positive change on the light of so many people around the world. Because yes, maybe, sometimes it is a drop of water in the ocean, but this drop of water can save a life here and there.

Many drops of water can save many lives and create a wave that mobilises people around the world in order to make it a better place to live, with equal dignity, and equal rights for every human being.

The other day, I was in Washington, and I visited the museum of – they do not call it the museum of slavery, they use a less controversial word, I think it is the museum of – American History, but in fact, it is the [museum of history] of slavery. It was not so long ago; it was not 500 years ago.

When one realises what the human being has been able to do to other human beings, at a moment when Christianity was wide spreading the values of universal love, it is really appalling, really shocking.

That is why I think that people like you have a lot of work to do and I thank [you] for that and I hope that we will be able to support you as much as we can.