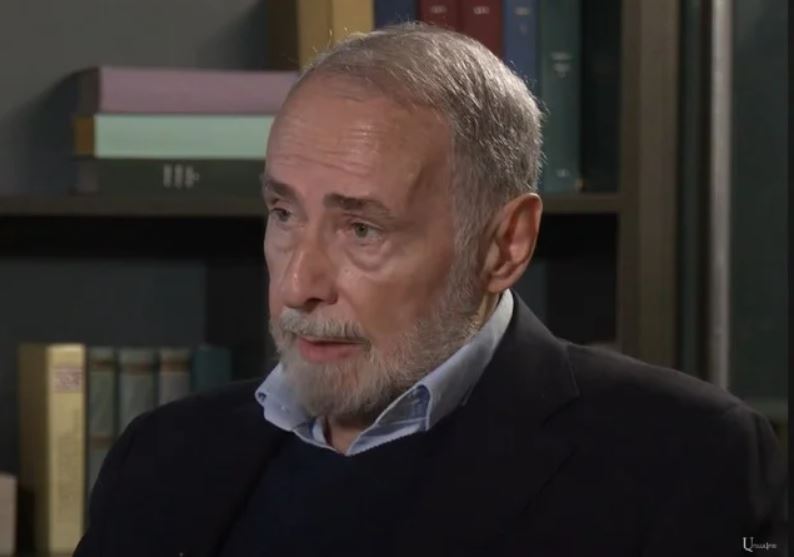

By Vahan Zanoyan

“One need not destroy one’s enemy. One need only destroy his will to engage.”

― Sun Tzu, 544-496 BC, Chinese General and military strategist, author of The Art of War.

Read also

Second only to the thousands of lives that were lost, the costliest casualty of the 2020 44-day war for Armenia has been the will to fight for a just cause — both in the government and in a significant segment of the general public. There is a symbiotic relationship entrenched between a war-weary, disillusioned and demoralized public and a populist government convinced that the only way forward for Armenia is to reach a peace agreement with its enemies even at the cost of conceding Artsakh and an apparent readiness to make further political and territorial concessions, even if they threaten the viability of the Armenian state. In the absence of a strategic national vision and purpose, the two reinforce and sustain each other.

This dynamic largely explains the survival of the present government in face of the cataclysmic losses of the 2020 war and the subsequent loss of Artsakh. The government’s peace rhetoric is what the public wants to hear. This, combined with its recently intensified public visibility and anti-corruption campaign, the absence of a credible opposition, and the vivid memory of the chronic monopolization and abuse of political power by successive governments since independence, will likely sustain the symbiotic relationship for a while; but that dynamic is not sustainable in the longer term.

What makes the current situation particularly worrisome is the fact that Armenia’s “will to engage,” to use Sun Tzu’s terminology (which connotes the will to confront and resist enemy aggression), seems to have gone missing in a cacophony of “justifications” which have implications and consequences far beyond what they’re meant to rationalize — namely, the prevailing public apathy and certain popular policies of the government. These justifications include arguments such as the call for realism, expediency, the importance of peace with Armenia’s neighbors and probably the deadliest of all, the deliberate and systematic belittlement and degradation of the nation’s collective memory and heritage, its history, national values, cultural identity, traditional values, war heroes and even the symbols held sacred by the Armenian nation for millennia.

The will to engage fades naturally once all that was deemed worthy of fighting for becomes marginalized. In this environment, even patriotism is made to look passé, an outdated burden.

Azerbaijan continues to do its share to mute Armenia’s will to confront its hostility — the systematic destruction of Armenian heritage in occupied territories, the constant threats and claims that Armenia is Western Azerbaijan, the military drills with Turkey at Armenia’s borders, the ongoing shipment of arms from Israel, the sporadic sniper fire across the border killing Armenian servicemen several kilometers inside the Armenian border with impunity, the refusal to honor international demands and court orders, the refusal to give any encouraging response to Armenia’s peace initiatives, are, at least in part, intended to scare and intimidate, with the hope of keeping the will for struggle and retaliation in Armenia under perpetual sedation. Azerbaijani leader Ilham Aliyev’s militaristic speeches belie his apoplectic mindset about what he calls Armenian “revanchism,” which he strives to bury once and for all.

But while the Azerbaijani strategy is clear and explicable, even if not defensible by international norms of conduct, the consequences of the Armenian strategy, whether intended or unintended, are more worrisome and more difficult to understand.

To be clear, this is not a call for warmongering. Nor it is a reckless nationalistic cry for revenge. It is a call to prepare for war, a war which is already upon Armenia, whether it wants it or not. The country is in a state of war when over 215 square kilometers of its sovereign territory remain occupied, including strategically important military positions, when 120,000 of its citizens and compatriots were forcefully expelled from their historic homeland in Artsakh, when Azerbaijan defiantly still illegally holds a large number Armenian political prisoners and prisoners of war, and when it still has territorial demands based on highly debatable Soviet era maps, which it backs by constant threats of imminent war.

Armenia’s pursuit of a peace agenda with the obvious lack of the will to resist aggression amplifies its vulnerability. Pleading peace from a brutal dictator who has the passion and political need to show further conquests is not sound strategy. Rather than compel Azerbaijan to the negotiating table, it boosts Aliyev’s appetite for more territorial and political concessions, especially when Azerbaijan, supported militarily and diplomatically by Turkey and Israel, has not yet experienced binding global checks on its use of force to achieve territorial and political objectives. Thus, it should not come as a surprise when Azerbaijan moves the goalposts for a peace agreement.

“Preparing for war” means taking the necessary steps, including many unpopular ones, to become so ready for the next war that one wins it before it even starts. For Armenia, that is the only way to have a just and viable peace.

Here’s a partial list of what that entails:

- Devoting the lion’s share of national resources to defense; this may require the unpopular step of diverting some funds from civilian infrastructure projects to military projects.

- Strengthening national, civil, and territorial defense capabilities to fit the next generation of technological warfare.

- Raising the morale of the armed forces by every means — organizational improvements, modernization, advanced training, attention to pressing needs, improving the conditions of border posts.

- Unifying, preparing, and mobilizing the population, both psychologically and physically, for probable enemy aggression.

None of these measures are being taken, at least not to a degree called for in a country which is in a state of war.

As part of the justification process, a dangerous mindset that seems to have seeped into official Yerevan thinking is that history is not a reliable guide to building a future and that one cannot draw lessons from history, because history can often provide conflicting lessons. (A similar idea was advanced by Gerard Libaridian in September of 2023 at a lecture at NAASR, which, although in a somewhat different context, also cast doubt on the idea that it is possible to learn from history. See the segment from min 26:30 to 30:30 of this link.) This mindset provides a pretext to ignore some invaluable lessons of history. While it is true that history is not an exact science, there are nonetheless irrefutable lessons of direct and immediate relevance to Armenia’s condition today, that can be drawn which are not subject to the vagaries of different interpretations of historical facts. It would be a grave mistake to dismiss them based on broad generalizations about the lack of adequate analytical rigor in historical records.

These lessons are so obvious and so simple that there should not be the need to even mention them. And yet many of the mistakes of the Armenian government stem from ignoring them. They include:

- It is next to impossible for any country to secure its borders solely by signing a peace treaty with its enemies. The opposite is true — i.e., once a country secures its borders by its own strength, it can have peace. Security can provide peace. Peace cannot provide security.

- The stronger of two enemies, especially one with expansionist ambitions, will not agree to peace, or sign any document which limits its options to use force. Even if it does, it will not honor its terms, while its enemy remains weak and vulnerable. This is a timeless and universal lesson of immediate relevance to Armenia today.

- Making unilateral and unconditional concessions to an uncompromising enemy never pays off. Recognition of Artsakh as part of Azerbaijan was probably the most critical strategic mistake, which could have been avoided if this lesson had been understood.

- Widely recognized values — human rights, democracy, right of self-determination, etc. — have no bearing on actual foreign policy formulation of nations who advocate them. What drives the process is national and State interests. “Values,” if they fit an already adopted policy, may be brought in as a further justification and to gain moral credit. But they do not determine policy. The silence of the West in the face of the ethnic cleansing of Artsakh is a good example. And even beyond Artsakh, this is probably one of the most pertinent lessons that any political leader of Armenia should draw from Armenian history.

- Over-dependence on any single strategic ally, especially in an alliance that is one-sided in the sense that one ally is much stronger, has more diverse geostrategic interests, and has significantly more to give to the alliance than to receive, is bad foreign policy. This is bad regardless of who the ally is. For Armenia, a one-sided over-dependence on the US would be as ill-advised as its one-sided over-dependence on Russia has been, albeit in different ways and with different risks.

Not only the right lessons have not been learned, but some wrong “lessons” or conclusions have been drawn, especially from the outcome of the 2020 44-day war and the subsequent September 19, 2023, ethnic cleansing of Artsakh. By far the most catastrophic of these is the claim that the loss of Artsakh was inevitable and pre-destined. That is probably the most pathetic attempt to exonerate the failures of not only the political leadership during the war, but also, inadvertently many of the mistakes committed during previous regimes of both Armenia and Artsakh since Independence — the implied logic being, ‘if our losses were inevitable, then they could not have been caused by our own mistakes.’ A natural follow-up catastrophic conclusion is that Armenia “wasted” thirty years and huge national resources trying to solve the “insolvable” problem of Artsakh.

That conclusion represents a precious missed opportunity to understand the true causes of Armenia’s failure and to learn the right lessons from it. Armenia’s mistakes during the 26-year period from the 1994 Bishkek Ceasefire protocol to the 2020 war — which essentially boil down to chronic complacency, criminal neglect of the interests of the State, and corruption — have been outlined in previous articles (see for example the section entitled Realism vs Defeatism in this article.) But it is worth bringing up two particular mistakes in the context of this article: First, Armenia’s failure to challenge the international recognition of Artsakh as part of Azerbaijan, which has no valid legal or historical basis; and second, Armenia’s failure to recognize how the interests of its strategic ally, Russia, and especially the interests of Russia’s political elite, had changed.

These lessons may seem irrelevant now that Artsakh is depopulated. And in the short-term, from a practical point of view, they probably are. But one consequence of refusal to learn from history is that it further erodes the will to engage, because the will to engage does not survive and thrive in a vacuum, but in the continuity afforded by historical context. Historical lessons are important even if they do not provide an immediate actionable policy.

Another dangerous position that has emerged is that the sole responsibility of the government is today’s Republic of Armenia, contained within its 29,800 sq km area. The country’s Coat of Arms (see segment from 4:30 min to 5:30 min) is deemed irrelevant to the Republic that was formed in 1991, and even Mount Ararat, which has been part of the spiritual and emotional Armenian Homeland for millennia, is rendered out of place within that 29,800 sq km area. The head of state teaches schoolchildren today that those who say Ararat is our highest mountain is not talking about Armenia but about something else — see segment from 4:20 min to 5:00 min point.

The deeper implications of this policy have a direct impact on Armenia’s will to fight for a just cause by casting doubt on the Armenian national identity. Also, and for the first time since the end of the Soviet Union, it formalizes the schism between the Armenian population living within the 29,800 square kilometers and the remaining Armenian population in the world. It drives a wedge between Armenia and the vast and invaluable resources of the nation.

While a single-minded pursuit of State interests is the government’s primary responsibility, it can neither justify nor condone the abandonment of broader national causes. In fact, if the main objective of the government had been to further the interests of the State rather than the interests of its rule, it would have worked very hard to protect Armenian interests and rights all over the world, and to harness their considerable capabilities to the service of the State. Any government of the Republic of Armenia has both an obligation and an immeasurable benefit from caring for Armenian heritage around the world, whether that be the Armenian Quarter in Jerusalem, justice in Artsakh, St. Lazarus Island in Venice, or the various communities in the Middle East and around the world.

Sooner or later, both the Armenian nation and the Armenian government will recover their will to engage, in the broadest sense of the phrase, because the current situation is anathema to the nature of the Armenian nation. That is the only way that Armenia can achieve the just and sustainable peace that the public covets today. Fortunately, in certain spheres, the private sector is already driving this process. There is a new, competent, and visionary generation thriving in Armenia today, which, unphased by the general malaise, proceeds to contribute to the development and strengthening of the country. It includes both professionals and fresh political thinkers. It does not yet have much say in government policy, but by changing reality on the ground and by example it can eventually lift the standards in both the general public and within government ranks. It remains to make sure that by the time this generation makes an impact, enough of the Motherland will still be standing and ready to embrace a renewed will to engage its formidable challenges.

(Vahan Zanoyan is a global energy and security specialist. Over a span of 35 years, he has advised 15 different governments on economic development policy, energy sector strategy, national security, and global competitiveness. He has also served as a consultant to numerous international and national oil companies, banks, and other public and private organizations.)