by Tamar Marie Boyadjian

The Armenian Weekly

They say that flying is meant for only birds and fairytales.

Is that true? At least that’s the truth they’ve been telling us.

Because that which seems improbable makes no room for

what can be possible. And so, the unreal remains in the

realm of fantasy, as part of that hidden truth that only

lives inside of you.

—Dr. Tamar Marie Boyadjian from The Mepe & the Dragon (Arpi Publishing, 2024)

I made up so many stories as a kid. A lot of them were influenced by the fantasies I read — even more were inspired by my loneliness. Characters were easy to get along with. They didn’t make fun of me, and they made for great friends. Plus, there were dragons and mythical creatures — I still love dragons. Every book was a new world, a new adventure. There’s never a dull moment when your best friends are books — and especially when they are fantastic ones.

I read all those considered “the greats”: Tolkien, Lewis, the Icelandic sagas, Homer, Virgil, Beowulf, medieval romances and the tales of King Arthur and Robin Hood, Malory, Celtic folklore and Dante. Books were all around me. Then, there were those written during the Victorian era, such as Ruskin’s The King of the Golden River and MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin. How dare I forget Morris, Wilde and Lovecraft! The medieval attracted me most; T.H. White sealed the deal. I didn’t know fantasy could be funny until The Sword in the Stone — Merlin would definitely tutor me with Wart, and we would both equally dislike Kay. In my world, young girls could train as knights, too. They could also pull swords from stones.

I always tried to picture myself in the imaginary world created by each fantasy series I read. I couldn’t tell if it was comforting or aggravating to know that I really didn’t belong there. Perhaps that was the point of the genre — to stand apart from anything imaginable. But I always wondered: what would these worlds look like if these characters resembled my extended family and me? Would I connect more to these otherworldly realms if they were built on premodern Armenian and Mediterranean stories instead of British or Western European ones? What would a mythical Armenian world even look like — especially when women are at the forefront?

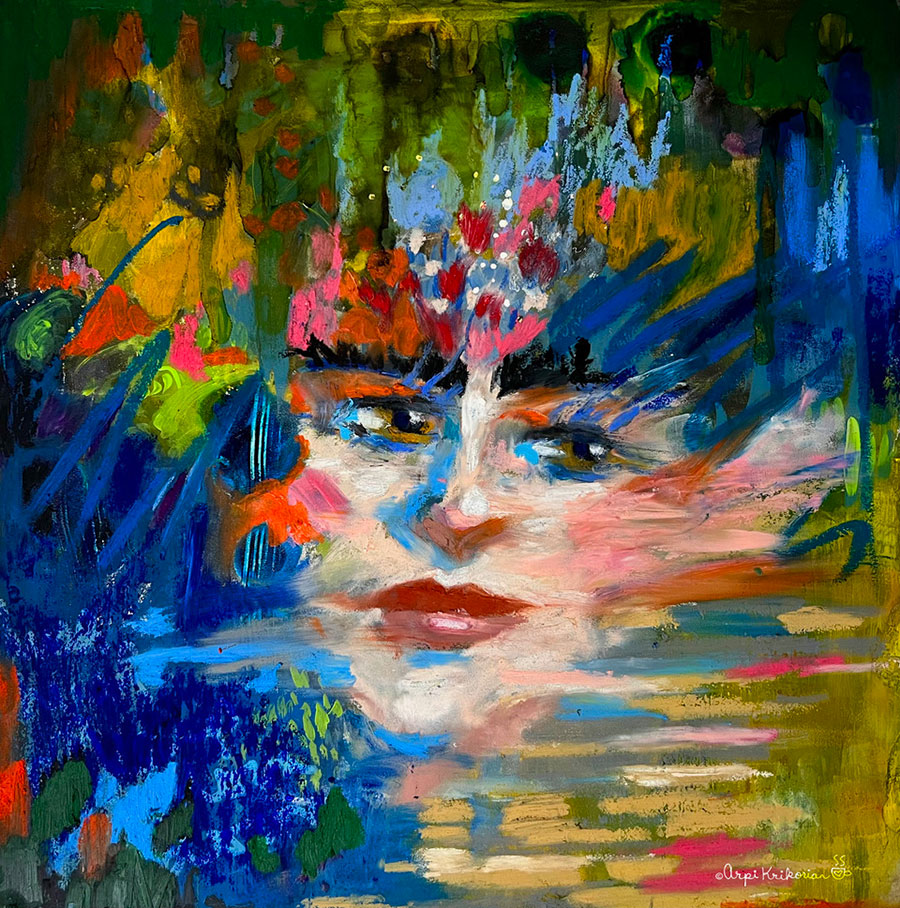

Perspective (Illustration by Arpi Krikorian, inspired by The Mepe & the Dragon)

I embarked on this quest: my treasure was not a grail but a book. I dedicated myself to this question while pursuing a doctorate in medieval Mediterranean literature with a focus on the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. I thought myself a Tolkien or a Lewis, and others did the same, too. Then I realized, as medievalists, why they not only taught fantasy, but also wrote it. I had the same urge as a teacher, because all the while I was learning about the awesomeness of the medieval world, I had created my own medieval world. The entire time I was reading hegemonic European narratives of the Middle Ages, I was rethinking their representation of the “Orient” and the “Armenians.” When I studied manuscripts and their premodern stories, I searched for those that included my own. Then, I searched for those written from the point of view of Armenians: what did they have to say about dragons and mythical creatures and knights, in bolorgir?

As much as early fantasy fiction centers itself around European crusading and colonial realities — imagining how kingdoms and national empires could extend themselves against “demonic and barbaric others” guised under the chanson of salvation — I knew that my world was not built this way. As much as medieval European romances use their narratives to reflect on the God-endowed grandeur of European conquests against Eastern Christians and the Arabo-Islamic world, I knew my world did not support these realities. And as much as the heroic adventures of premodern epics and romances lacked fully-formed female characters, I knew that women in my world did not exist only to support — or sometimes to trick or inhibit — a man’s journey. They were deserving of character profiles, too.

I searched for these women. I discovered very few. I discovered Sahagtukht and Khosrovitukht. I read their surviving words; I drew from their courage. And so, I began to bring my world to life, one Armenian letter at a time. My world was not only Armenian; it was also built on Hittite, Urartian, Mesopotamian, Persian, Arab, Georgian, Greek and other traditions and nuances. In my world, autonomous leaders are called mepes; there are also mythical trees and legendary creatures, like the aralez. I began to translate this world and converse with my characters. Like a method actor, I identified with each personality’s emotions and motivations. I already knew their stories; they were composed on palimpsests inspired by intentional expeditions through Armenian verses, which were once etched on ancient and medieval vellum.

Everything I read contributed to my worldbuilding. Of course, I was also determined to read every fantasy book written in Armenian. I found myself back again in the premodern. I read grapar. I re-read the Armenian epic. I re-read the histories of Movses Xorenatsi, Pavstos Puzant, Ghazar Parbetsi, Agathangełos and many other authors. I read and searched for Armenian folktales and legends. I was introduced to these authors and stories as a child when I attended Armenian school; I had revisited them in grad school. How could I have forgotten that Armenians also had dragons? That they even rode on them? That Xorenatsi tells us the children of Aztahag were dragon-born? That supernatural characters also filled these pages? It was as if time had erased the possibility of modern fantasy even existing in Armenian.

Why is it that Western Armenian has not experienced fantasy up to this point? What does it mean to compose fantasy and worldbuild in a language that is considered “endangered” and “dying?”

I thought about the way the premodern was taught to me in Armenian school. I remember learning about the father of Armenian history, Movses Xorenatsi. I remember reading sections from his History in the modern Armenian translation. I had never considered his History as something else — as also an imaginary. I also remember reading the story of King Arshag and the Persian King Shabuh from the History of Pavstos Puzant. When Arshag was tested by Shabuh and asked to step on Armenian soil, he spoke his truth confidently: “This is the realm of the Arshaguni dynasty, and if I return back to my world, I will take great vengeance on you” (my translation). What was Arshag’s “realm” and “world?” Yes, it was Armenian. Yes, it was Arshaguni. But, as children, why couldn’t we imagine it?

These texts were written in classical Armenian. We knew we were reading histories originally written in our ancient language. But, when we read them in Western Armenian, they felt old and distant from us. Imagining mythical worlds in English was not difficult. We had so many examples to draw from. Throwing ourselves into created geographies, backstories and invented languages felt effortless in English. We could not do the same in our own language, because when we read from our ancient books, we never considered them as creative efforts — they were history. They were taught to us as facts. They were taught to us only to validate our past.

So, our teachers drew our attention to the long-lasting presence of the Armenian people. We learned about our historical kingdoms to authenticate our place in the ancient world. Our teachers drew attention to our perseverance. We learned about our history as a way of pointing to our determined existence — even beyond the trauma of war, the Hamidian massacres and the Armenian Genocide. All this left very little room for the imagination, for a fictional universe — especially in Western Armenian.

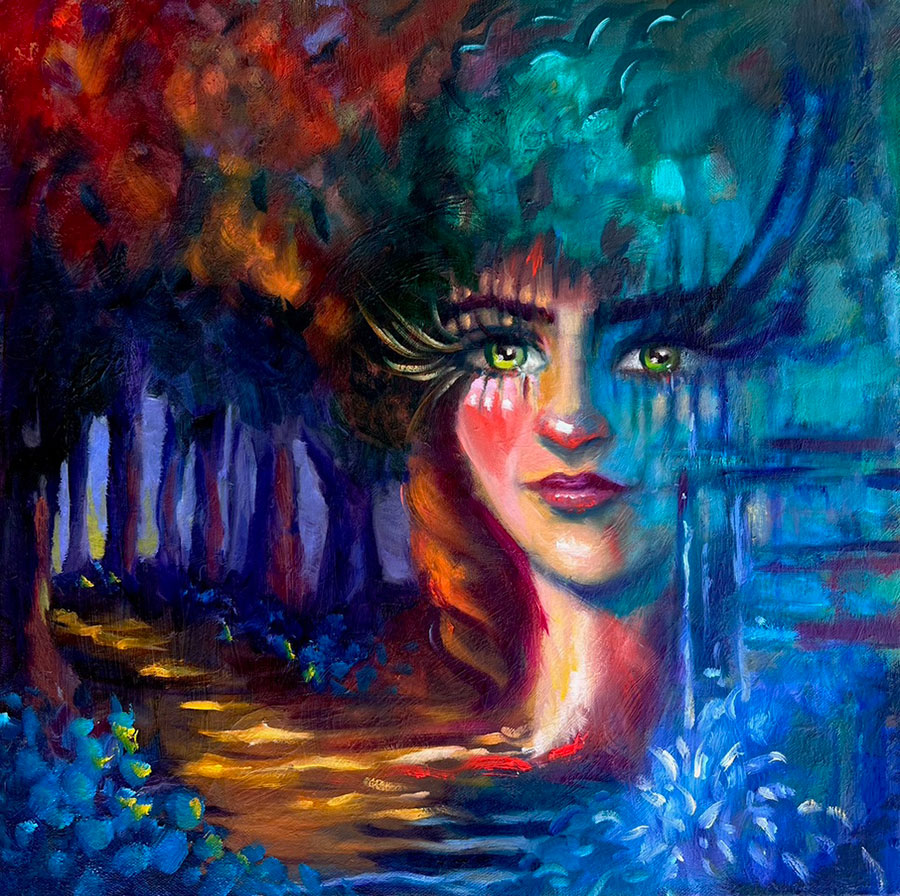

The Secret Portal (Illustration by Arpi Krikorian, inspired by The Mepe & the Dragon)

Arguably, the evolution of the genre of fantasy is futurism. To move beyond the tropes that make up early fantasy fiction means to create imaginaries that are not based on colonial models of history and the world. Contemporary movements of futurism — such as Armenian Futurism, Afrofuturism, Indigenous futurism, Arab futurism and others — combine fiction, history and fantasy as part of their worldbuilding. They aim to connect diasporas with forgotten and premodern ancestries; they rewrite a past that is not based on suppressive realities. Futurism liberates our way of thinking by helping us move beyond our generational trauma to healed spaces. Futurism reclaims the past to empower the present. Futurism allows us to create possibilities that were once unimaginable. Futurism allows us to manifest healed worlds. I consider my fantasy series as part of the movement of Armenian futurism, because it strives to do all of that.

I believe that writing fictional fantasy in Western Armenian can only seem like a possibility when we also embark on the journey of healing ourselves from our generational trauma. It does not mean we forget, but it means we permit ourselves to imagine other worlds without feeling like they are betrayals to the memory of our ancestors. Writing fantasy in Western Armenian means having a different understanding of our ancient and modern Armenian history. We allow ourselves the room to think of books as having mythological and folkloric elements; again, this does not mean we are saying our history is a myth. Writing fantasy in Western Armenian means forming a different relationship to our language. It means thinking of Western Armenian as not just a vessel for cultural preservation. It means that we can create, play and imagine in Western Armenian — and we give ourselves consent to do so. Rather than focusing on the “death” of the language, why not bring it to life by building worlds with it? Rather than focusing on only the tragedies of our past, why not tell our history in ways that allow for visual connection — like Roger Kupelian does in East of Byzantium I: War Gods and East of Byzantium: Warrior Saints and Sergei Parajanov does in The Color of Pomegranates?

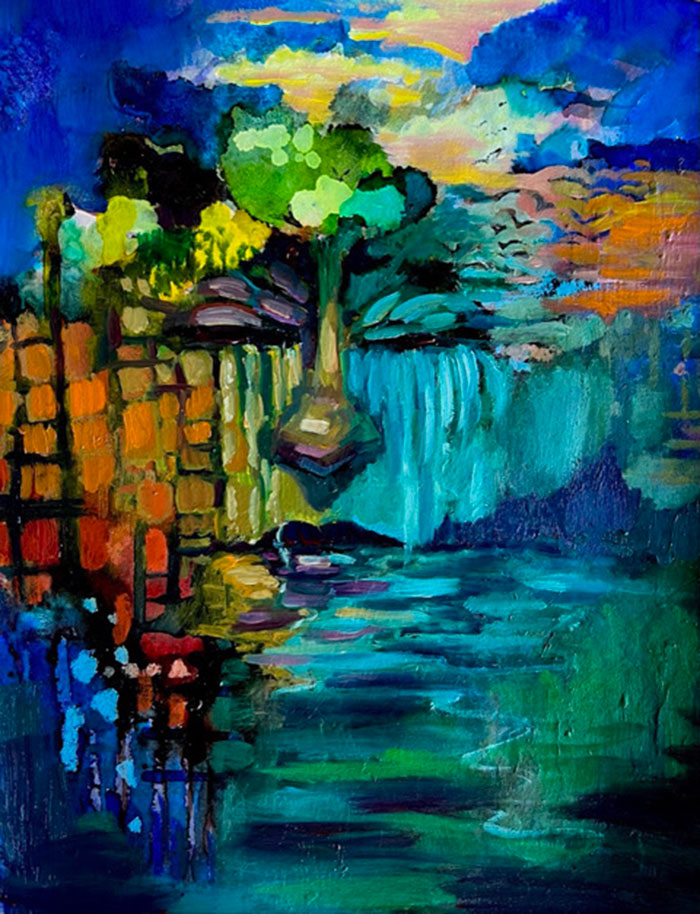

I Want to Break Free (Illustration by Arpi Krikorian, inspired by The Mepe & the Dragon)

But, how can we begin to imagine worlds in a language that continuously demands conversations about preservation? If we were to let go of our fear of losing Western Armenian, we could also think of what we gain through the language. If we start to think of speaking and writing in Western Armenian as acts of community-building, rooted in love — rather than efforts that divide us and are rooted in fear — we can also begin to imagine a living language; we can begin to think of alternate universes where we not only belong, but also thrive. We can confront our generational trauma, heal and dream together. By building together, the improbable can make room for the possible.

Does the unreal only remain in the realm of fantasy? Only if we lose sight of faith. Sometimes, we are lucky enough to earn the faith of others in our journey. I feel blessed to have earned the support of many on this journey, including my friends and family. Most importantly, I was able to earn the support of Arpi Publishing. When I received a phone call from pioneering visual artist and founder of the press, Arpi Krikorian, I knew that the world I had created was beyond the mere genre of “fantasy.” When she told me that my series in Western Armenian was accepted by the press, I knew that others could be part of it too. Then, I was honored to learn it was the first of its kind. With so few presses in the world that even publish books in Western Armenian, I knew that writing the book wasn’t enough. Without Krikorian’s vision and efforts in supporting the creation of original Western-Armenian works for children and young adults, I wonder how many books would have been lost or not even written. Krikorian and Arpi Publishing are allowing my book to take flight — instead of being some sort of long-lost fairytale.