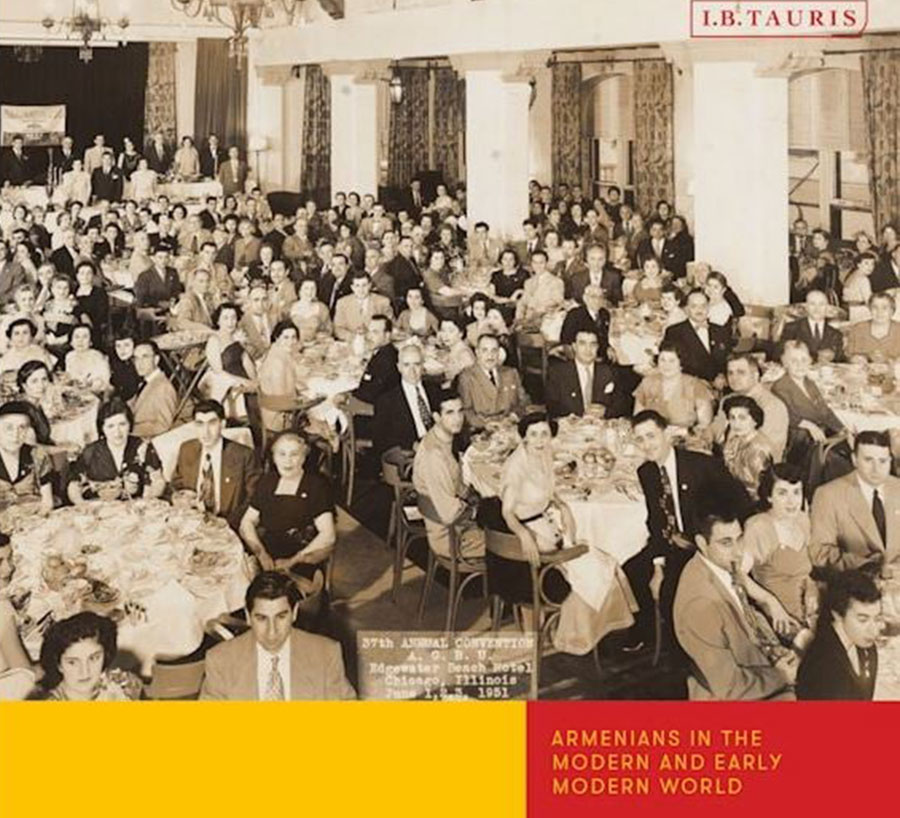

Subtitled “Armenian-American Culture and Politics in the Twentieth Century,” Benjamin Alexander’s sociological study sheds interesting light on events that shaped immigrant life in America for both survivors of the Armenian Genocide and those who preceded them at the turn of the 20th century.

Started as a doctoral dissertation at the CUNY Graduate Center in 1998, Ararat in America follows a rough chronological order. After a cursory 20-page overview of 3,000 years of Armenian history, Alexander moves on to several chapters with titles such as: “The Contested Homeland: the First World War and the Genocide” and “Years of Adjustment: Armenian Americans in the 1920’s.”

These and the third chapter, “The Tourian Affair: Contested Memories and the Archbishop’s Murder,” are the most successful in the book.

I, for one, live just two blocks away from Holy Cross Church in Washington Heights — where Archbishop Tourian was brutally murdered during a Christmas service by ARF zealots — but I knew little about the details of the conflict that led up to this tragic event which has had ripple effects well into the 21st century. Other important questions that Alexander discusses in this volume include the following: how does a persecuted people which has suffered a genocide regroup in a new country thousands of miles away from their homeland? How do they divide themselves politically and otherwise? Why do conservative modes of thinking continue to dominate these communities, as they simultaneously assimilate into American society and take on its more progressive, liberal modes of thought and habits?

Read also

The book also contains fascinating information about figures such as General Dro and amusing anecdotes about arranged marriages and dating at mid-century in certain Armenian circles.

However true it may be that much of the Armenian-American community was once divided along the Tashnag/Ramgavar split in both its secular and religious incarnations, this has lessened in importance as time has passed.

The last chapter, “The Power of a Word: Naming and Claiming the Genocide,” is perhaps the least satisfying in no small part because it ignores almost all the Holocaust and trauma scholarship done by fine scholars such as Shoshona Feldman, Marc Nichanian and Taner Akçam, as well as seminal work by filmmakers such as Claude Lanzmann and Atom Egoyan on the impossibility of knowing or understanding the genocidal will to annihilation. But my main criticism of Alexander’s book is simply that it lacks complexity and often oversimplifies such as when he uses sentences like “a good Armenian” and “a good American.”

Another vexing problem with the book is that it needs to be copyedited: there are simply too many repetitions, typos and stylistic inadequacies.

More disturbing perhaps, is the author’s glossing over of groups of Armenians such as emancipated women, feminists, agnostic/atheists, LGTBQ + people, as well as Armenians who grew up in half-Armenian and half-gentile “odar” families, or Armenians who had at one point become assimilated but later went back to their roots. Nor does Alexander discuss in any serious way, for example, important groups such as Catholic and Protestants Armenians who have contributed mightily to Armenian culture in general and Armenian-American society in particular.

There is also the question of methodology and research, which is top-heavy with traditional conservative historians. Apart from the cursory mention of Stuart Hall and Benedict Anderson, Alexander ignores the contribution of important philosophers and thinkers such as Edward Said, Fernand Braudel, Michel Foucault and Hayden White and their contributions to theories of culture and colonialism.

There are also statements that simply seem wrong, such as the following: “The East had a simple rural virtue and a touch of mystique, the West (as exemplified by Western youth) had the sophistication, and the task of Armenians, was to find just the right blend.” Assimilation always involves sacrifice, but Alexander’s generalities fray the reader’s nerves. Stereotypes about the East and West and so-called differences between Armenian Americans and their host society which ignore their difference vis-à-vis Soviet Armenia and the post-Soviet Armenian republic render argumentation problematic. Which East is Alexander actually referring to? The lost lands of Western Armenia? Lebanon and Syria? The First and Second Republics?

I do not want to seem unfair to Alexander. This is after all a modified dissertation of only 180 pages — clearly, an enormous amount of work went into writing it. To his credit, the book is meticulously footnoted and gorgeously printed. Perhaps the thing to do would have been to restrict his field of enquiry to something like: “The Role of the Tashnag Party in Armenian Politics” or simply to write a longer, more ambitious study.

Alexander seems like a thoughtful, intelligent scholar who will perhaps write a more insightful and inclusive volume in the future.