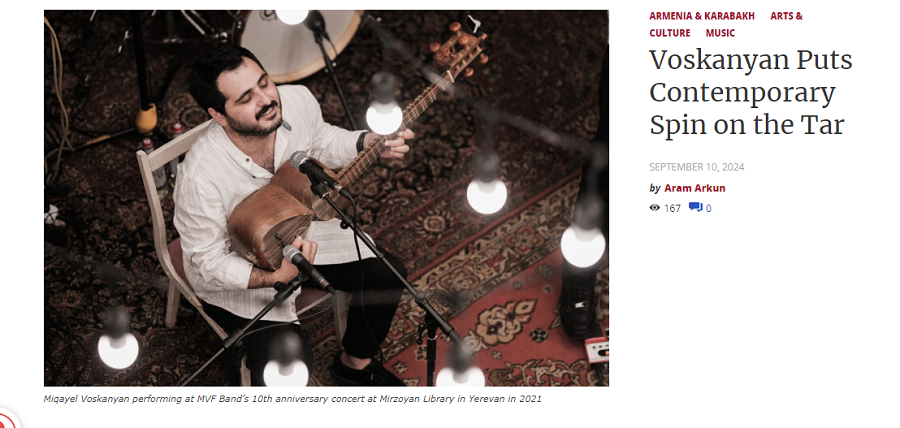

WATERTOWN — Miqayel Voskanyan has been drawing more and more attention to Armenian tar music in recent years on an international level. He is a composer and singer as well as an instrumentalist, and recently was in Boston to participate in Silkroad’s Global Musician Workshop of the New England Conservatory. He is the leader of the five-man Mikayel Voskanyan and Friends Band and the smaller Tarup Trio.

MVF Band at Royce Hall, University of California, Los Angeles, 2023 in the scope of its Center Stage US tour

What Is a Tar?

Voskanyan explained that the tar is an Iranian stringed instrument in origin but there are actually two types, Iranian and Armenian. He said, “The differences are huge between the Armenian and Persian tars. I can mention some of these differences, like shape, wood, the number of strings, the technique — because Iranians play the tar like a guitar, while Armenians hug the tar — and the sound.”

Read also

For Voskanyan, the sitar sounds more like the Armenian tar than the Iranian one. He said, “The sound of the Armenian tar is more wooden, while the Iranian one sounds more metallic.” The Afghani rubab, he added, also sounds more like the Armenian one than the Iranian.

The Iranians have their own repertoire of classical music, different from what Armenians play. Armenians, he said, use it for a greater variety of music, including folk and traditional music, as well as an orchestral instrument, performing music composed for concerts with orchestras. The Armenians have played the tar since at least medieval times, if not earlier, Voskanyan said, and this is borne out by references in medieval manuscripts and sculptures, including khachkars (cross stones).

In Soviet times, Voskanyan said the tar became called the Caucasian tar because it was also performed in neighboring countries, including Georgia. However, Voskanyan said that in that country, it was the Armenian minstrels who played the instrument, not native Georgians.

On the other hand, Azerbaijanis do play the tar. He said the founder of the professional performing school of tar in Baku, which was a more cosmopolitan city then, was an Armenian named Soghomon Seyranyan. The Armenian version of the tar was used and played in the Armenian fashion. Today, he said, there are many Azerbaijanis who play the tar, in part because of governmental support of this.

Innovation

Voskanyan said that he feels lucky to have traditional training in playing the tar. He said: “At the same time, I say that if you just play a list [of musical pieces], you are doing something wrong. It is excellent that we have this type of music, but we have to develop it. Let’s not make traditional music like something in a museum. When I started, I found new techniques, new ways to play. I started to improvise. I used different kinds of music — jazz, rock, funk, and classical, and I found that everything is possible on the tar. I do fusion, and I started to create my own compositions. I then gathered musicians and founded my band.”

He said that the development of tar music is primarily an individual thing at present, as there are no schools for modern Armenian music in general. In Armenia’s music schools, like the Komitas Conservatory, they either teach classical or traditional music, and furthermore, there are no separate schools for instruments like tar or kamancha. Instead, musicians are taught how to play an instrument as part of an ensemble.

“Armenians like to do fusion because our traditional music and our instruments are very flexible,” Voskanyan said. Armenians have done this more many decades, including in many countries abroad such as the US. He said that one can do Armenian fusion with Western-style jazz, rock, with Eastern style music, including Persian and even Chinese or Japanese music as well as with African music.

He did something new too. Voskanyan said, “I changed the way of fusion music. I decided to make Armenian fusion jazz or pop fusion music based on instruments — not to use the instrument to feature the music, but to make music around my instrument. I started to compose music for the tar, and with my band, we started to do arrangements around the tar.”

While it was a type of fusion music at the start, Voskanyan said, “Over the years, we developed our music, and I and my musicians founded a unique sound…It is very difficult to say what genre it is. It is modern Armenian music. Afterwards, some musicologist can find the right word for this genre, but I do not care to find a name for it.”

Voskanyan added that in recent years, he also tried his hand at composing in different realms, such as for choirs, string quartets, and chamber groups. He also started to do film scoring during the pandemic period. He said, “That is when I started composing for others. Film music is a very good area for that. You can see the movie and compose to create emotions for it. Because I am a cinephile, I was interested in doing this, and I liked this process. I still want to do more films.”

He primarily scored short films, which he found more interesting to do musically than feature films because of the challenge of limited time. There are a few instances when films use him performing traditional melodies, but usually he composes original scoring. He was given a cameo in Michael Goorjian’s recent film, “Amerikatsi.”

Musical Roots

Voskanyan was born in Yerevan in 1986, while his family has roots in Artsakh, Syunik, Ayrarat and Tavush. He said that he was attracted to music as a child. His father played dhol and sang, and his grandmother also was a good singer, but they were not professionals. Voskanyan began performing on stage at the age of 5, and became a member of a children’s folk instrument orchestra in Yerevan. Some of his relatives and friends also joined. He went to a regular school, but from age 9, he also began attending a music school simultaneously.

He recalled, “I chose the tar only with my soul. I heard how this instrument sounds and chose to learn to play it. That was in 1995.”

Initially, Voskanyan wanted to learn the kamancha [spiked fiddle] because the director of the children’s ensemble, Hrachya Muradyan, was one of its great players, and he inspired all the children in this way. However, as there was no one who played tar in the orchestra at that point, they played the tar for the children and its sound, which he had not heard before, he said, changed his mind.

He found out later, after he had already started to learn to play this instrument, that his great-great-grandfather Sargis, who lived in Ijevan, was one of the best performers of the tar in Armenia in the 1920s and 1930s. Voskanyan said that he had never met him, and even his father never had met him, but Voskanyan’s grandfather remembered him. Unfortunately Sargis’s tar was broken and irreparable, but Voskanyan even today said that he keeps the body of the instrument as a memento.

For seven years, Voskanyan said that he pursued tar and also vocal studies, but then decided to add one more specialization when he attended Yerevan State University (YSU) from 2005 to 2009. He graduated with a degree in art and music history. While at YSU, he also took classes from various professors and musicians at the Komitas State Conservatory, but not as a regular student.

In the early 2000s, he began to work in the State Orchestra of Folk Instruments of Armenia as a tar player, though for a few years he supplement his income by working as a tour guide. He took part in various musical ventures as a sideman playing with different musicians, but made the audacious decision, together with his friend Lusine, who later became his wife, to launch his own musical projects. In 2011 they created the band MVF.

In music school, he learned also to play the piano. He later did learn also to play the saz, oud, bouzouki, guitar and other similar string instruments.

He said that while he was just starting out, he used to compose lyrics along with melody, but then focused on composing the instrumental portion of music. Now, he said, he again sometimes tries to write lyrics. When he performs, she said, “Sometimes I don’t think — I just sing and play. In improvisational music, there is an energy which you don’t fully understand. I suddenly see that I am both singing and playing.”

Armenian Music in Today’s World

Voskanyan said, “I notice that we [Armenians] do not represent our music much. Our music is very interesting, so people want to know more about it. We have a great heritage and a huge legacy of unique music….When we had Greater Armenia [historically], it was a big country and we had more neighbors than now. We had an influence on those nations, and they had an influence on us. That led to different styles of music, such as in Artsakh, Taron, Hamshen, Tigranakert/Diyarbakir, etc.”

It is quite an effort to reach a broader audience, he said. He exclaimed, “Armenia is like an island, a very little island, and it is very complicated [to break out].” He said that the easiest way is to release music digitally, though sometimes physical copies on vinyl are more suitable, depending on the value of the music.

However, he said that you need specialists to help you in this process, while artists stick to their composing and performing. It remains difficult to do this while in Armenia, he said. Armenian artists who have entered the global market like Rosa Linn (Roza Kostandyan) benefited from having management based in the United States.

Voskanyan said that he is lucky because he has his own team and company working on disseminating his music. He cofounded his company, called Oberton Music, with his wife, Lusine, in 2018. He said it was the first multigenre music label in Armenia.

As a music management company, he said that it also tries to help other artists besides Voskanyan to develop and to enter the world music market. This includes Armenian artists living abroad. Most recently, for example, Oberton Records released Armenian-American vocalist Lucy Yeghiazaryan’s album, “Beside the Golden Door,” on vinyl.

Digital releases and the Internet are not enough, Voskanyan said, especially if the goal is to take the music and culture to a global audience.

“Digital music is just not the same as live music,” he remarked. “People must listen live to understand all the energy and the background.” Also, collaborations with other musicians and other cultures are important.

Consequently, he said he strives to travel outside of Armenia. As one of the most successful musicians in Armenia, he is invited to participate in various festivals or programs and sometimes, he said, his band does its own tours and programs. One year he traveled abroad once a month, while another year he did not travel at all. “It is not regular yet. I dream to make it stable because it is very important for a musician not to stay in his location. For me, it is like a mission. With my tours, I can explain my culture. I can give master classes about my culture, about Armenian music from ancient to modern times. I myself can also develop, expose myself to many influences, communicate with musicians, agents and producers, and of course help my music culture to get more visibility by being present in person.”

Voskanyan said that even in Armenia, it is not easy to preserve traditions. There is more globalization and Armenians accept a lot of things into Armenian life. He said that it is good to reflect all cultures, but it is important to know and feel our own culture strongly.

Contemporary Armenian music has an important role to play in this. We live in contemporary times, he said, so naturally we can feel this music as close to us. “At the same time,” he said, “contemporary music is a gate to enter other periods of time, at least for me. Using contemporary music, I can open the door to ancient music.”

He said, “Today, we have some undetermined things in our identity, especially in this post-war time. Some people are tired of being Armenians. But at the same time, when you go to your roots and feel your roots, there is a physical power. You can see your power and do more good things.”

Music in particular, he said, has a healing dimension. He chose fusion some 15 years ago as a way to make his music more interesting to different types of people. But now, many people have come back to their roots. He said, “I can play tar not using fusion but just tar, and they can understand it, and they feel good when they listen because they are transported to their roots and given power.”