The Armenian Weekly. In the shadow of conflict, the transformation of cities often reveals deeper layers of strategic intent. Artsakh, a region long entangled in geopolitical strife, provides a striking example of how urbanism and architecture can be weaponized beyond traditional military engagements. In the aftermath of the 2020 Artsakh war, the landscape of Artsakh has been reshaped not only by the ravages of battle but also by a deliberate and strategic overhaul of its urban and infrastructural fabric.

This article delves into the concept of “militarized urbanism,” a strategy often employed by authorities to exert control over indigenous populations, as seen in the West Bank where Israeli authorities use this approach against Palestinian natives. The article specifically explores how Azerbaijan has utilized architecture and construction as instruments of colonial dominance in Artsakh. With the region’s complex history of Armenian-Azeri tensions and recent territorial occupation, the “rebuilding” and “restructuring” efforts undertaken by Azerbaijan serve a dual purpose. On the one hand, they aim to project an image of modernity and progress ahead of COP29, to be hosted in Baku this fall; on the other, they are intricately designed to consolidate control, assert territorial claims and destroy the cultural heritage of the indigenous, ethnically cleansed Armenian population.

By examining recent developments in Artsakh — ranging from the creation of “smart villages” to extensive infrastructure projects such as new airports, roads and energy facilities — this article reveals how these initiatives are more than mere reconstruction. They represent a strategic deployment of urban planning, architecture and greenwashing to reinforce military occupation and manipulate socio-political dynamics.

‘Net zero’ emissions

Read also

Azerbaijan’s global influence, both militarily and economically, is underpinned by its extensive oil and gas reserves, which fund about 60% of the government’s budget through fossil fuel exports to Europe. This stance persists even though Azerbaijan, like all nations, committed to moving away from fossil fuels in accordance with recommendations at the COP28 U.N. climate summit in Dubai.

As Baku prepares to host COP29, Azerbaijan aims to present itself as a leader in clean energy and emission reductions. Central to this narrative is Nagorno-Karabakh and its neighboring regions, which have been designated as a “green energy zone.” The government plans to implement a range of renewable energy projects, including installing a dozen hydropower plants and attracting foreign investment in solar and wind energy.

Azerbaijan’s broader goal is to increase the share of renewable energy in its electricity capacity from seven percent in 2023 to 30% by 2030.

Additionally, Azerbaijan aims to achieve “net zero” carbon emissions in Artsakh by 2050, as outlined in its most recent national climate action plan (NDC) submitted under the U.N. climate framework. This plan includes developing “smart” settlements, promoting green energy zones, enhancing agriculture and transport and reforesting thousands of hectares in the newly-occupied territories.

Reconstruction in Artsakh

The Republic of Artsakh is rich in natural resources, particularly in its seven regions, which encompass about 246,700 hectares of forested land. The area also contains two hydropower plants and three mining sites. These resources are crucial for Azerbaijan, enabling it to diversify its energy sources, including alternative energy, which is a key focus of the Azerbaijani government’s economic strategy. This emphasis on new energy sources is highlighted by Azerbaijan’s decision to restructure its administrative divisions, creating two economic regions — Zangezur and Karabakh — that cover the entirety of Artsakh.

In 2021, the Azerbaijani government allocated 2.2 billion manats (approximately 1.3 billion U.S. dollars) for the restoration and development of these regions. The government plans to implement projects under “new modern standards.” Various foreign organizations are engaged in projects to reinforce the economic benefits of Azerbaijan’s territorial control, with a focus on large-scale decarbonization, renewable energy, green buildings, waste management, clean industry, natural climate solutions, and integrated energy and mobility systems.

During a press conference on February 26, 2021, President Ilham Aliyev revealed several ongoing reconstruction efforts in the newly-conquered territory, including the construction of three new airports, roads and tunnels. The strategic placement of these airports near key cities is intended to solidify military control, reflecting a calculated approach to consolidating Azerbaijan’s occupation of Artsakh.

One such example is the village of Aghadzor (Aghali). Aghali serves as a model for approximately 30 similar “smart villages” that the Azerbaijani government intends to build throughout the seized regions. These villages are part of a massive construction initiative in the Karabakh area, funded by Baku at nearly $2.5 billion annually — about 12% of the total public expenditure. Azeri officials in charge of the construction claim that a nearby screw hydro turbine generates electricity for the entire village and the homes are outfitted with solar water heating systems. Additionally, “smart agriculture” will provide employment for the over 860 residents who have already relocated to the village, with expectations for hundreds more to arrive shortly. Despite the official vision of an eco-paradise, Baku’s rapid implementation efforts have transformed the landscape into a vast construction zone, as observed and illustrated by satellite imagery.

Lachin blockade

In December 2022, Azerbaijan leveraged environmental concerns in the protracted conflict over Artsakh. Azerbaijani “environmental activists” blocked the Lachin Corridor, the sole road linking the region to the outside world, essential for food and medical supplies. These “activists” claimed to be protesting against the environmental impact of mining in the region. However, the protesters were sent by the genocidal regime in Baku, a claim denied by an Azeri COP29 spokesperson.

Four months later, Azerbaijan set up a permanent checkpoint on the road to “prevent the illegal transportation of manpower and weapons,” ending the sit-in but continuing the blockade with limited aid reaching the region. U.N. human rights experts reported that food, medication and fuel shortages plunged the region into a humanitarian crisis.

On September 19, 2023, Azeri forces launched a swift attack on the remaining Armenian-controlled parts of Artsakh, which Baku described as “an anti-terrorist operation.” Within 24 hours, the de facto government of the enclave surrendered, announcing it would cease to exist the following January.

Over 100,000 ethnic Armenians, nearly the entire remaining population, were ethnically cleansed from their historic homeland.

Now fully controlling Artsakh, Azerbaijan is intensifying efforts to reshape the region and resettle tens of thousands of Azeris there. “We will continue the ‘Great Return’ campaign until all those who were forced from their homes can go home,” said the COP29 spokesperson, referring to internally displaced Azeris.

Destruction of cultural heritage

The government of Azerbaijan is using its extensive construction project in occupied Artsakh as a pretext to erase the region’s ethnic Armenian heritage. Erasing centuries of Armenian history and culture, this relentless campaign has resulted in the demolition of government buildings, historic monuments, churches, cemeteries and entire communities.

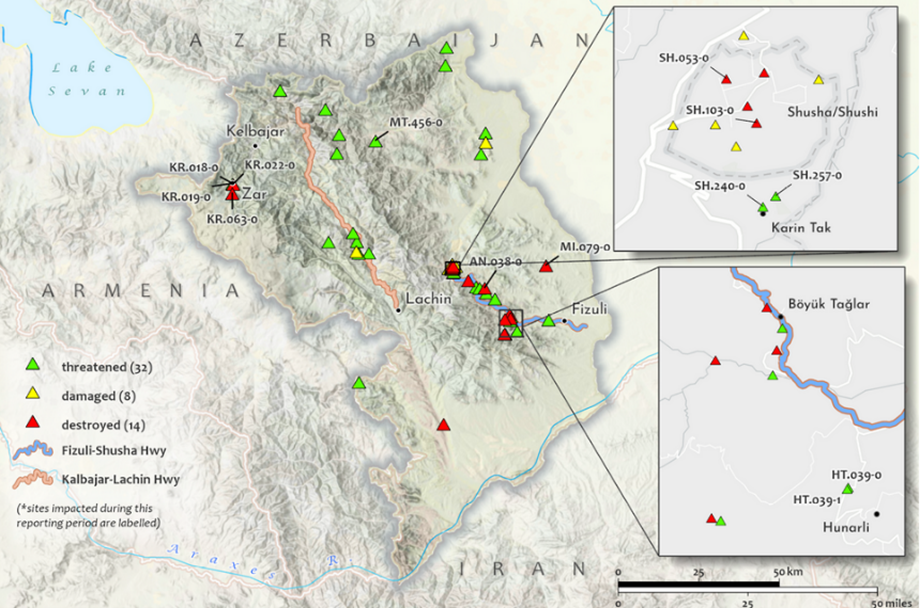

181 Armenian heritage sites have been added to the watchlist of the Caucasus Heritage Watch (CHW), a research program led by archaeologists from Cornell and Purdue Universities, throughout the course of the last year. There are now a total of 489 sites on the list in Artsakh.

“The Armenian cultural legacy of Artsakh might be severely impacted by COP29 preparations. Large-scale infrastructure and redevelopment initiatives are putting cultural sites in the path of constant earth movers and endangering, harming or destroying them,” according to CHW. The much-awaited COP29 falls just a couple of weeks after the one-year anniversary of the ethnic cleansing of Artsakh. Azerbaijan, following its recent military conflict, plans to promote COP29 as a “COP of peace,” emphasizing the prevention of climate-driven conflicts and advocating for green solutions to geopolitical issues.

One of the many examples documented by the CHW is the case of the recently demolished Kanach Zham (Green Chapel) Church and the Ghazanchetsots Church Cemetery, both located in Shushi. The St. Hovhannes Mkrtich Church (Kanach Zham) was severely damaged during the 2020 Artsakh war, with one of its two iconic cupolas being destroyed. Subsequent satellite imagery from April 4, 2024 indicates the complete demolition of the church by Azeri occupying forces.

CHW reports a 75% increase in destroyed sites and 29% in threatened sites in Artsakh since the ethnic cleansing of its indigenous population, with the percentage only predicted to increase as the COP29 date nears.

The region around occupied Shushi has been the main focus of the Azeri government, in a bid to establish the now ghost town as Azerbaijan’s “Cultural Capital.”

The Center for Territorial Construction and Planning of Azerbaijan awarded the Shushi redevelopment master planning contract to Chapman Taylor, a world-renowned U.K. firm with a history of collaboration with the Azeri government. It is the main designer of many landmarks in Baku, including most famously the Port Baku Towers. The master plan was first presented to Aliyev on August 29, 2021, and was recently leaked to the public. It includes the typical sustainability buzzwords of “green belts,” “park networks” and “pedestrian friendly design.”

The centerpiece of the proposed design is a new mosque, located right on Ghazanchetsots Avenue. It is strategically placed to overshadow the iconic Ghazanchetsots cathedral, which has been de-crossed and its domes removed by the occupying forces. The new mosque is being constructed in a former residential neighborhood that housed families of veterans of the Artsakh Liberation War. A quick look at the masterplan shows the cathedral listed as a “cultural element,” but that does not guarantee the safety and integrity of the church and its surroundings, which have both been damaged and demolished.

Chapman Taylor’s master plan was met with controversy on the grounds of its failure to mitigate human rights risk. U.S. law firm Kerkonian Dajani LLP filed a complaint with the U.K. National Contact Point, accusing the global architectural firm of violating OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. The complaint, made on behalf of the Avan Shushi Partnership, alleges Chapman Taylor’s redesign of Shushi contributed to adverse human rights impacts on the indigenous Artsakh Armenians.

The Avan Shushi Partnership, which owns the Avan Shushi Hotel & Tourist Center, claims Chapman Taylor was hired to redesign Shushi after the Azerbaijani military took control of the city in November 2020, marking buildings and homes for demolition without consent. “It is clear that our hotel was modified, repurposed and rebranded, and this was done without our approval or consent,” stated Alec Baghdasaryan, Avan’s lead partner.

The complaint asserts Chapman Taylor did not adhere to the OECD guidelines to mitigate human rights risks and instead proceeded with its work amid ongoing abuses. According to Kerkonian Dajani LLP, Azerbaijan’s actions aim to erase Armenian heritage in Artsakh, and Chapman Taylor failed to leverage its influence to mitigate these impacts.

Azeri sources and concerned citizens have also been vocal with their complaints, arguing that the government did not announce a tender for the multimillion-dollar contract, an atypical move for such a large project. Additionally, they highlight the lack of transparency regarding the construction firms involved in ongoing projects in Shushi and Artsakh, with only a vague reference from Aliyev indicating that these firms would be from “friendly countries.” Concerned citizens have also expressed frustration over their exclusion from the master plan’s design process, as decisions are being imposed by the Aliyev regime with the full cooperation of Chapman Taylor.

This situation is highly unusual, as large architecture firms handle master planning projects through a structured process. They start with consultations and research, engaging with stakeholders to understand goals and context. Initial findings lead to conceptual frameworks and design options, visualized through plans, renders and CGIs. Regular stakeholder meetings ensure alignment with community needs. These steps are all missing, as the only information available is a leaked plan from the press and vague statements from Azeri politicians including the usual sustainability buzzwords.

In conclusion, the Azeri government’s initiative to establish “smart villages” and agro-industrial parks across occupied regions is a strategic facade. While these developments superficially incorporate traditional Azeri architecture, they mask the underlying military motives of a settler colonial project. By promoting this concept of “smartness” and aligning it with national values, the government crafts an illusion of technological advancement and redevelopment. This portrayal serves to justify the substantial financial investment in these projects, branded as part of the “Big Return.” Ultimately, these efforts are not merely about modernization but are tools for asserting military dominance and control over Armenian territory.

Architects and urbanists bear a profound responsibility to safeguard cultural heritage, serving as stewards of the identity and history of the communities they work within. Their designs must not only reflect the beauty of local traditions but also protect them from the looming threat of erasure. In a world where architecture and infrastructure are wielded as weapons of colonial intent, we as professionals must remain vigilant and courageous. We must act as sentinels, sounding the alarm when cultural landmarks are at risk of being obliterated by oppressive forces or when foreign styles are imposed to erase the rich tapestry of local identities.

The stakes are high: the erasure of cultural heritage is not merely a loss of buildings or sites but a devastating blow to a community’s sense of belonging and continuity. Each architectural choice has the power to either uplift or marginalize, to either celebrate diversity or enforce homogeneity. The duty to detect and act as an early warning system extends beyond immediate architectural choices. It requires a critical awareness of broader socio-political contexts and the potential implications of one’s work. Architects and urbanists must educate themselves about the histories of colonialism and oppression in the regions where they operate, understanding how their designs could inadvertently perpetuate inequalities or contribute to systemic injustices.