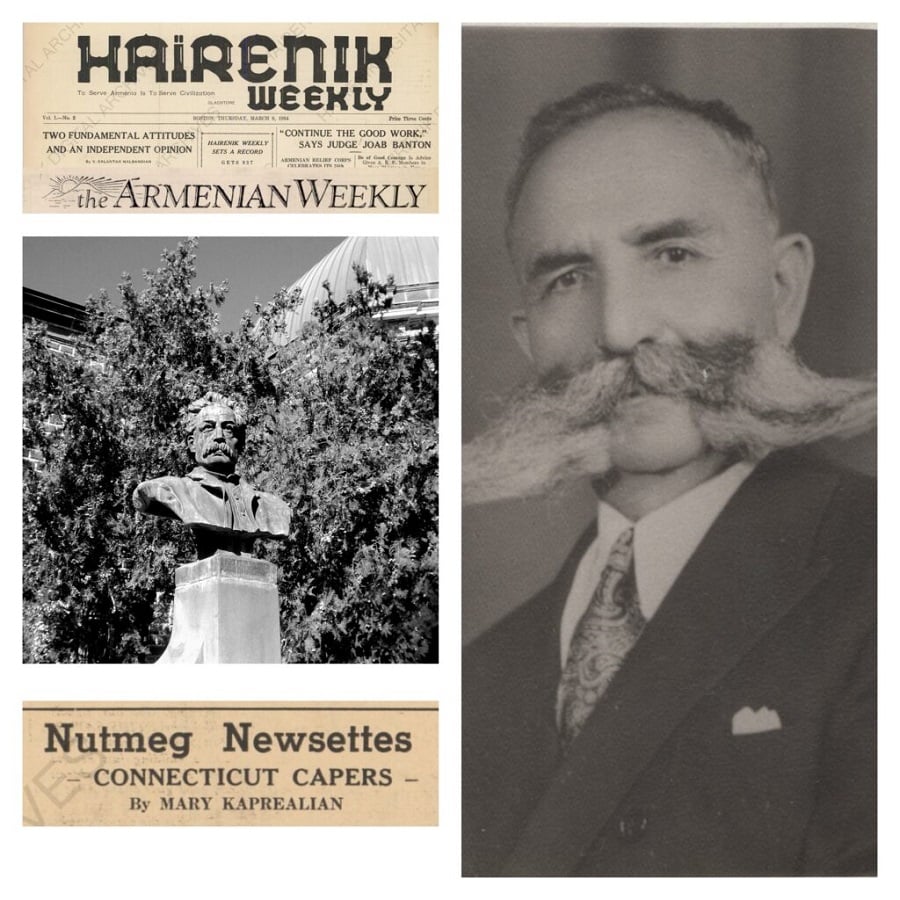

The Armenian Weekly. This marks the inaugural issue of The Armenian Weekly in its 91st year.

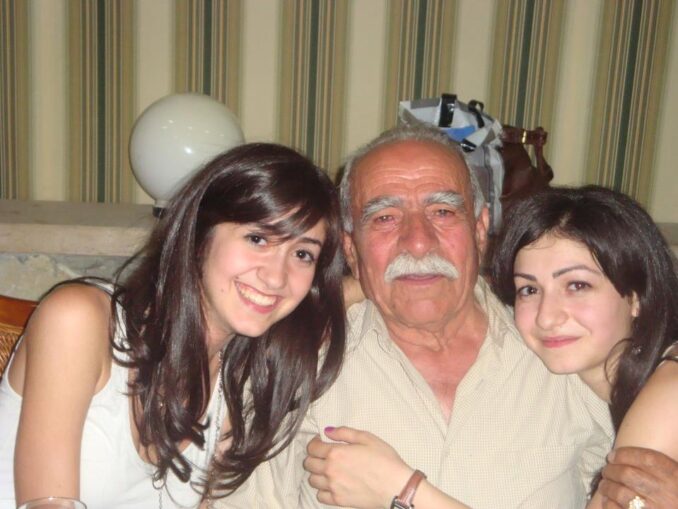

A milestone, yes — but for me, it’s also a time to reflect on the weight of history and the legacies we inherit. My grandfather, Patvakan “Honorable” Papik, lived through the tumult of Soviet Armenia and saw the last days of Artsakh. He died on the same day we lost Karvachar: his 91st birthday — a man and a homeland, gone. One buried in soil, another abandoned on our tongues.

Every year since, when the first snow falls, I listen to Yernek te ays nor tarin. “If only this New Year” would bring an end to our pain.

The Armenian’s pain. The people’s pain. The pain of this earth.

The lyrics were penned by Raphael Patkanian, a 19th century Armenian poet and revolutionary. In our history, the lines crossed often.

Patkanian was born in Nor Nakhichevan in Russia — itself a recreation of the original Nakhichevan, where Armenians believed Noah first rested after descending from the Ark on Mount Ararat.

Just a few years ago, Azerbaijan’s ruling forces bulldozed all traces of its Armenian past — destroying 98% of its cultural Armenian heritage sites in what has been described as a cultural genocide. Today, Nakhichevan’s bones lay in Azerbaijan, as Ararat sits in Turkey.

At the time of Patkanian’s life, Armenia was caught between three colonial empires: Ottoman (Turkish), Persian and Russian. Themes of a liberated Armenia were replete throughout his works.

In the latter quarter of the 19th century, the swath of territory that we now call the Caucasus and the Balkans were caught between these two warring empires. These events fueled burgeoning nationalist sentiment, which in turn fueled the late-stage terror and paranoia of the Ottoman Empire.

Patkanian believed — and he believed sincerely — that Russians would save his Armenian siblings from Ottoman yoke.

Patvakan, by contrast, had no such faith. When his children would return home from school, where they sang the praises of Lenin Papik, he would tell them a story, passed down from his father.

“In 1915, three empires conspired to kill us. Andranik asked Shaumian to go to Lenin — to ask for 20,000 guns, so that we could protect ourselves. ‘We don’t need soldiers, just weapons,’ he said. And Lenin replied, I’d rather a small people be eradicated than have the revolution fail.”

In 1915 as in 2020 and 2023, Patvakan saw the cost that false idols were willing to pay — and he fell with their latest betrayal. These days, especially, I think of the aspirations of our intellectuals and activists of yore: where they laid the tracks — and where they fell short.

We remain shackled to the hope of a liberator — only to gift us with new chains.

Last year, I wrote, If only this New Year, there will come an end to all saviors and victims.

If only this New Year, clamped fists would puncture the rubble, to lift a finger upon death. Upon man-machines, built in defiance of all that is sacred.

If only this New Year, we all will free ourselves from small-mindedness, from power-lessness, from soul-conquest, once and for all.

This year, I ask, what do we envision as we head forward with a shrinking homeland and a growing ocean?

There is a distance between our communities, between our tongues — literal and imagined. It’s as though the clock is desperately seeking to rewind to the year-that-must-not-be-named. And, as with all clocks, someone is doing the winding.

Everywhere, pain and fear find a home in rage. Righteous and wrought.

But rage condemns us to see only black in the white. We become night creatures with a blood lust, seeking to right a wrong. This is the rules-based order: a game of sheep and wolves.

We are neither sheep nor wolf. Mocking another’s pain is not our game. It’s the oppressor’s. A black and white world is not our world. It’s the colonizer’s. There’s no mine versus yours. Zero sum has never been our fight in a world of empires, conquerors, looters and thieves. A world where orchestrators of genocide walk free and bombs barrel down in the name of democracy.

You don’t have to agree with every perspective of a party, person or platform, but when you look into a pair of eyes, try to see the sincerity of their pain and the color of their truth.

That is the diversity — the source of strength — that this world seeks to destroy. My grandfather was a man of integrity in a world that places a price on everything. True to his name, until the very end. Stubborn, but fair. Conservative, but open to new information. When he spoke, soft and slow, the room went silent. Now, when the family gathers, no one commands that kind of respect. Everyone is hustling, trying to blunt pain with the next fix. We hardly see ourselves in each other anymore.

There is a contradiction here. That peace is most painful after the war.

After the war, my friend stitched me a bookmark that says խաղաղ | khaghagh, “peace,” after I told them that it was my favorite word in Armenian. It might just be the one word you could say to your dentist with your mouth open, mid-cleaning, mouth half-occupied.

Khaghagh. 91 years, Papik came and went and never tasted the word. He was clean in a world of oil.

Clean like Zahrad’s tongue, narrating a woman’s hands cleaning lentils. Zahrad: the first generation of Armenians born in Turkey after the genocide. Ground zero, adding up the world into one Christmas tree.

“All the splendor, all the beauty, all the light are not enough to cover up the blood seeping from your branches.”

“All the blood, all the tears, all the sorrow are not enough for us to hang our hearts once again from your branches.”

Zahrad pushed against the idea of Armenian as a dead language of a dead people on a dead land. Through humor, with almost painful simplicity, he observed. Living, breathing, speaking a language on a land that can’t even tolerate our ghosts. Khaghagh, willed in the mouth, despite the blood.

Like Siamanto, our once-editor-turned-martyr, who wrote of human justice, “I spit in your face!”

On your chakat (forehead). Spit as ink. Chakat-a-gir. The writing on the forehead.

Last week, piano virtuoso Tigran Hamasyan posted a snippet of himself singing The Well of Death and Resurrection.

He captioned the photo, “Happy Year-end to all!”

Instead of Happy New Year, a happy end of year. Reflective, papering through the past rather than projecting onto the future. The death of the year — let it be happy. We dial back the clock, to re-rib.

From կողմ | koghm — “side” to կող | kogh — “rib.”

There is a reason the cage is covered in flesh.

Picking a side is like picking your favorite rib. A zero sum war. Paterazm. Here again, we get that beautiful double consonant, from ghm to zm. Pat means wall in Armenian. War builds walls inside us. Brick by brick, kogh-arr-kogh.

A wise man once said, “People lie most during war, after hunting, and before elections.”

Now, we’re after elections, in-between the hunt, and before the (new) war. In this period, we must brace ourselves.

May we reflesh our ribs and refresh our branches. Truth and justice: two ribs in the cage.

Color, buried beneath flesh.

Christ on the cross. Reminding us that there is no light in despair.

Novelist James Baldwin’s timeline began before the Civil Rights Movement. As a poor, black, gay man, he had much reason to grieve. But he never despaired about the world, because “you can’t tell the children there’s no hope.”

And here, I turn again to Armenian. The clues are already written.

յուսահատել | hoos-a-hatel (hope + to cross/to cut) means “to despair.”

But with a slight tweak of the first vowel, we get յոյս ա հատել | hooys-a-hatel, meaning “to cross hope.” Where hope flips despair inside out.

Psychotherapist Esther Perel describes her parents’ renewal on life post-Holocaust as the difference between “not being dead” and “being alive.” Indeed, many genocide survivors lost faith — for how could there be a God after what happened to us? And if there is one, God must be vengeful and not all good.

But that was rare. Many — if not, most — survivors lived the rest of their lives with an unshakeable belief. They may not have been warm, but they did not renounce the light. Instead, they chose to see God in each other. The truth in their eyes. The pain in their dictates. Hooys-a-hatel.

It’s why the forced atheism of the Soviet system did not work. My mother’s parents were deeply devout. My parents, a crisis of faith. My generation is reaping the consequences. Trying to form a cross in our mouths, beyond metaphor or stone, for hope to find a home.

But it would be naive to think that pen and prayer alone will solve the myriad existential questions before us. The work is long, intersectional, multidimensional, and full of mishaps and missteps along the way.

With the utmost respect and admiration for Patkanian, there will never be an end to suffering or pain. And yet, our ancestors found the strength and resolve to greet the sun every morning.

Think even of our death rituals. When a loved one passes, we say, Astvads Hogin Lusavoreh, “May God shine a light on their Soul.”

And here, I’m reminded of the hooys-a-hatogh (hope-crossing) wisdom of the late Silva Kaputikyan: the poetess of Armenia and tireless advocate for the Mother Land, the Mother Tongue, and the Mother and Child.

Even if you are desperate

Even if you are weak

You have no right to give up your weapons

Whatever happens

Even if the last soldier falls

You, Armenian poet,

Have no right to not believe in the eternity of your people.

This is a birthday that Papik never saw, but his legacy, like that of the paper, endures. As we head into The Armenian Weekly’s 91st year, may we let in the light to see the eternity of each other.