WATERTOWN — The series of horrors that befell Artsakh (Karabakh) starting in 2020 with the loss of much of its territory and ending in 2023 with the expulsion of its population and its total take over by Azerbaijan were felt by those in the diaspora yet obviously from a safe distance. Karabakh natives who lived through this experience were scarred in a different way.

One young man and his family endured not only the bitter loss of their home and land to usurpers, but lost so much more during the inferno that engulfed a depot in Berkadzor, near Stepanakert, on September 25, 2023, where citizens of the city, desperate to flee before they were overrun by the Azeri army, had gathered, after hearing that there was possibly fuel available for sale. In the ensuing fire, more than 220 died and more than 300 sustained injuries.

Read also

To this day, there is no official reason for the inferno that engulfed the depot. Some say it was the work of the Azerbaijanis, while others suggest that the fumes from the gas tanker combined with the actions of a careless smoker might have set off the explosion.

Nelson Sargsyan was 17 when he accompanied his father and uncle and cousins there on that fateful September day. The resulting explosion was so forceful that his uncle’s body has never been found while he and his father suffered from extensive burns. Nelson, luckily, survived; his father did not.

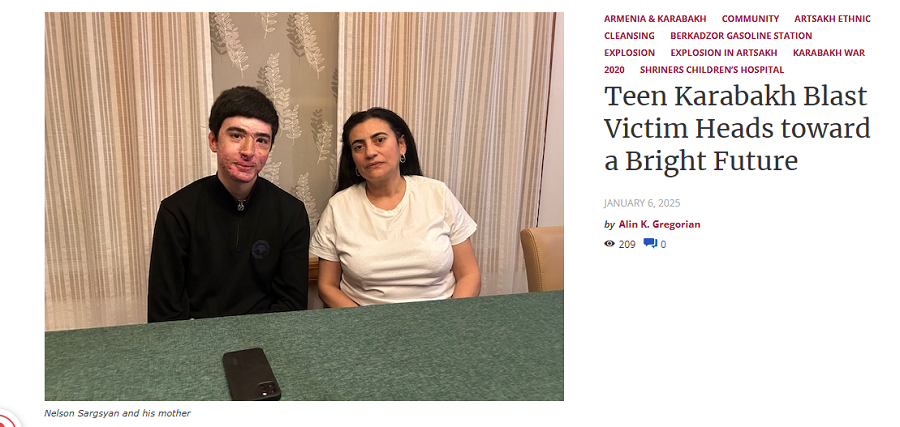

Over dinner this December, at the home of Stepan and Talin Chiloyan, Sargsyan and his mother, Lylia Mardyan, spoke about what they had gone through as well as the road ahead. In addition to Nelson, she has two daughters, Takouhi and Arous, both younger than Nelson.

Mother and son were in the US for a second stint at the Shriners Children’s Hospital in Boston, where Sargsyan is undergoing extensive treatment for his injuries. His first stay at Shriners was January-April 2024. His treatments have resulted in nothing short of a miracle.

It is important to note that not only is the treatment free at the Shriners, but the hospital also offers free housing for families.

From Blockade to Escape

The majority of Karabakh (Artsakh) was invaded and taken over by Azerbaijani forces in 2020. Only Stepanakert and its immediate suburbs were left to be run by the Armenian enclave’s leadership. In December 2022, the Azerbaijani Army imposed a blockade on the Lachin Corridor, the enclave’s only connection to Armenia and thus the outside world. In November 2023, Azerbaijani forces fully invaded the enclave and forced out every Armenian, under threat of genocide. A handful apparently remain there, either too old or frail to leave.

Nelson’s mother, Lylia Mardyan, is a petite, elegant woman with sorrowful eyes. She recounted how as the blockade continued and life became progressively harder, the population did not lose hope.

Nelson Sargsyan with Boston Bruins players including Marc McLaughlin (26), Justin Brazeau (55) at Shriners Hospital in December

Speaking in Armenian, she recalled, “During the blockade it was very difficult. There was no bread, and when there was, there were long lines at bakeries. There was no food nor sweets for children. My sister would help me by sending meat from the village. We felt we were suffering but would emerge victorious after [so much] suffering.”

She and the others did not think that they would have to leave and that the Armenian republic would cease to exist. The government’s messaging was more positive, suggesting that an end to the blockade was near, she said. However, she noted that at one point, the government issued an edict that basements and bomb shelters should be cleaned out and preparations should be made to take shelter in case war broke out.

“One day the government announced that everyone should prepare a small bag with necessities and passports and important documents, because there might be something. The people kind of ignored it and thought the army is fighting and we have [already] suffered for nine months,” she recalled, meaning that they expected a positive result.

There was little connection with the outside world. Medications had run out so the Red Cross would take the more gravely ill patients to Yerevan. In addition, the Russian forces would sometimes arrive with trucks bearing tea or food. “The lines were very long,” she said. To help her, she said, her sister would take Lylia’s three children to the village for a couple of months to ease the food burden.

In September, Mardyan recalled, when school was about to start, the parents were frantic because there were no new clothes, but still the kids were sent to school and there was hope for victory. All that changed on September 19, when all of a sudden, there was a loud explosion, and they realized that war had broken out.

“The children were at school and the teachers had led the children to underground shelters,” she recalled. She hurried back from her job at a nursing home.

At the time, it was hard to make calls on cell phones as the war had interrupted regular service. Nelson, she said, went to pick up her youngest, Arous and took her to their aunt’s house. She picked up her daughter Takouhi and the two also went to her sister’s home. They hid in the basement and she remembers being told that the Azeri army was close by and that it was not possible for the Armenian and Artsakh forces to hold them off. They all went to the church basement and awaited the end of the war.

Newly-installed President Samvel Shahramanyan surrendered and ended the war, she said, because if it continued, the entire population would be wiped out, similar to 1915, she said.

Her husband, Ashot, had been serving in the army in Artsakh for 20 years. He and other relatives were serving in the Martakert region, surrounded by the Azeri army for several days.

A couple of days after their return, they heard that at a certain location in Stepanakert, there was some gas for sale. Everyone was looking for gas to get out.

A group from the family, including Nelson and his father, Ashot, and his uncle, Artur, headed to the depot.

“They had gone there hungry in the morning and we had just baked bread,” she recalled. As the hours passed, she said, “We kept calling them but they did not answer.”

“The explosion happened,” she said, just managing to get the words out. They still did not know.

Finally her sister was able to get in touch with Ashot, who said that he and his son were injured and that his brother-in-law was nowhere to be found.

“We ran there and everyone was calling for their relatives,” she said. “People were screaming in the blast zone.”

They went to the morgue to check for her brother-in-law but they could not find him. “Until now he has not been found,” she said.

Nelson recalled the events of that terrible day. “When the explosion happened, we wanted to walk out of the area. There were many dead people. I saw so many injured people. My dad kept saying leave. I wanted to help but it was very hard,” he said. “It was so hard.”

In fact, Stepan Chiloyan added something that the humble Nelson had not; he said while Nelson had been burned by the blast, the injuries to his hands were not extensive. However, it was when he tried to help someone up who was fully engulfed in flames, that his hands suffered horrific burns.

Chiloyan, of Watertown, is a retail sales manager at Sovereign/Santander Bank. He frequently visits Armenia as his daughter lives there.

Nelson is quick to smile and has a charming personality, though his difficult experiences are never far from his mind. When asked what he would like to do as an adult, he said, “Once my hands get well, I want to become a mechanic,” he said.

Asked how he was bearing up with all that he has endured, he choked up and replied, “I have to; I have two sisters and my mother.”

Treatment in Armenia

On September 26, Nelson and his father, along with several other burn victims, were transported to Armenia by a Russian military helicopter. The rest of the family followed on September 27.

Ashot Sargsyan was in the hospital in Armenia for nine days and even endured the amputation of his arms but succumbed to his injuries. Nelson left the hospital mid-November. He would still go back regularly to have his bandages changed.

A few days after the arrival of the wounded, she recalled, the hospital authorities allowed parents to visit their children. The sights and sounds from that time still haunt her.

“There were so many boys, calling for their mothers. They were all burned, with the smell of burned flesh in the air,” she said. Almost 20 died in the hospital.

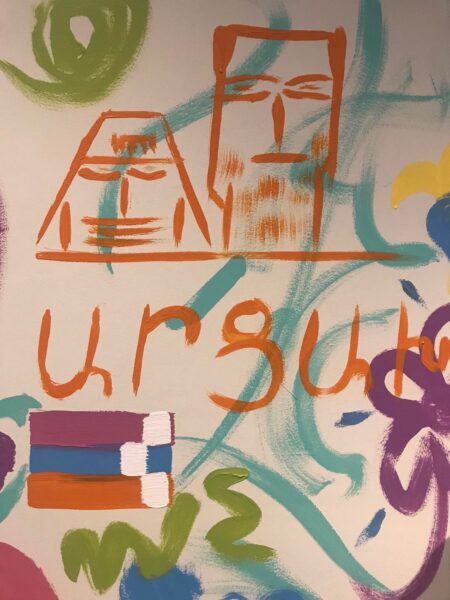

The hospital allowed patients and families to pain something special to them on a wall in their wing. Nelson and his mother chose to write “Artsakh” and paint the famous Mamik-Papik sculpture

While Nelson suffered extensive burns to his face and body, his hands bore the brunt of the injuries because he was trying to help someone. “When the fire happened, he was trying to get out of the hole. He saw his father, his uncle, his cousins and got excited. He turned around to help others. During that time, someone was burning. He extended his hand to help him. That person’s skin melted on his hands,” Chiloyan said.

Nelson’s suffering did not end with the horrific explosion. As Chiloyan related, after the accident, while he was being treated in Yerevan, the doctors gave him little in way of painkillers despite his tremendous injuries and therefore he did not let them work very much on his hands as the pain was unbearable, and infections had set in.

Nelson said that the doctors told him, “You are a boy. You can take the pain.”

Mardyan said that for the last visit to the Yerevan hospital, her sister, a nurse, insisted on accompanying Nelson. She recalled that her sister told her she had fought with the doctors, telling them that if the treatment continued in the same way, Nelson would lose both hands.

“There is no hot water at the hospital to loosen the scabs to clean them,” Mardyan said. Instead, she was told to wet Nelson’s wounds at home and then bring him to the hospital, in the freezing December cold.

“When I would complain, they would say you don’t understand,” she said.

She added that this was why Nelson was at first reluctant to go to Shriners, worried he would endure the same pain. However, he was happy to be wrong.

Chance Encounter Leads to Shriners

A confluence of events helped bring Nelson for care to Shriners. Stepan Chiloyan had approached the hospital after the explosion to see if more victims could be brought to Boston after a couple were brought here in the immediate wake of the accident. The hospital said yes, as long as they met the requirements.

Visiting the Yerevan hospital one day was Dr. Salpy Akaragian, a Los Angeles-based nurse and founder and director of the Armenian International Medical Fund. Akaragian holds a doctorate in nursing and is director emeritus of UCLA Health’s International Nursing Program and Nurse credentialing. Her NGO focuses on providing cochlear implants in Armenia.

Lylia said that Akaragian saw that Nelson’s hands in particular were severely burned and asked if he would be willing to come to the US for medical care.

Chiloyan, visiting Yerevan, then approached Akaragian after he met with Nelson and suggested that he be brought to Shriners. Akaragian agreed and handled the paperwork and Chiloyan arranged the tickets.

Added Chiloyan, “They arrived here on January 5, 2023. I picked them up from the airport and went straight to the hospital. Two days later they worked on his hands.”

“The skin on his hands was black,” Lylia said. Since then, between surgeries and medication, Mardyan said, Nelson has improved tremendously. Both his hands and his face have undergone tremendous improvement. Not only has normal color been restored to the skin of his hands, but the treatments and operations have given him full use of his hands.

“Until I came the first time, I couldn’t do anything on my own — eat, or get dress or bathe. Now it’s much better,” Nelson said.

Lylia praised Chiloyan for being there for them through all the surgeries.

The first step at Shriners was a meeting with Dr. Robert Sheridan, director of the hospital’s burn service, to assess his needs.

“The first meeting was really hard for Nelson and us, to see his pain. Once they undid the bandages, the wounds and the tissue were infected. They hadn’t cleaned the wounds well,” Chiloyan said.

Someone who eased his pain — literally — was Dr. Gennadiy Fuzaylov, an anesthesiologist at Shriners, who for the first time was able to calm Nelson and treat him. Chiloyan said that the doctor was extremely kind, sitting with Nelson to make sure he was reacting well to the anesthesia.

Plastic surgeon Dr. Daniel N. Driscoll at Shriners has also worked on Sargsyan, who qualifies for free care at Shriners until he is 21.

The wounded young people from Artsakh who previously received treatment at Shriners are Henrik Azroumanyan, 14 and Arman Asryan, 16. Again, Chiloyan and friends stepped up to raise money for their care.

Chiloyan said the main impetus for the young people to come here was the local Armenian American Medical Association, and its former president, Dr. Rosalynn Nazarian. The group is now led by Dr. Hovig Chitilian.

Another member of the organization, Dr. Shant Parseghian, helped Mardyan get her diabetes in check, Mardyan said.

Before leaving, Nelson met with a surgeon to see if his tendons could be strengthened in his hands. Plans for the next visit include work on his hands and laser on his face.

While here, Chiloyan and his son, Sipan, took Nelson to an NBA game and they have taken him to his favorite place to eat, Shake Shack.

From left, Lylia Mardyan, Nelson Sargsyan, Very Rev. Hrant Tahanian, John Aftandilian and Stepan Chiloyan at Shriners Hospital in Boston (St. Stephen’s Armenian Church photo)

Life in Armenia

Mother and son returned to Armenia on December 15.

During the interview they spoke about their life in Yerevan. The family members are still not citizens of Armenia. They get 50,000 drams a month from the government, but the payments don’t come when they are out of the country.

Lylia and her three children live with her sister and her children, making for a total of seven in a one-bedroom apartment.

“Difficulties are a part of life,” Chiloyan said, “But you need to be positive. Life goes on.”

Mardyan added that having kind people help them has this intolerable situation bearable.

As for their future, it is still up in the air. Asked if they planned to stay in Armenia, Mardyan responded, “We want to go back to Artsakh. But Armenia, I am not sure. It is very difficult for us. We can’t get jobs as Artsakh citizens. They say you have to be a citizen. If you are a citizen the children have to serve in the army. The pay is low and rents are high.”

In addition, Mardyan said that there is some lingering resentment by Armenians about the loss of their sons in the war.

She added that renting a place is very hard. When she called around to rent a place for her and her three children, she was often told that without a man in the household, there would be a question of how they would make ends meet.

“They said they could not rent us the place,” she said. “I told them we get money from the government but they still hung up on me.”

The family needs financial help for their day-to-day lives. Fundraising has been done at St. Stephen’s Armenian Church, as well as St. James Armenian Church.

In addition, Stepan Chiloyan has started a fundraiser for the family. To donate, visit https://gofund.me/34f535b9.