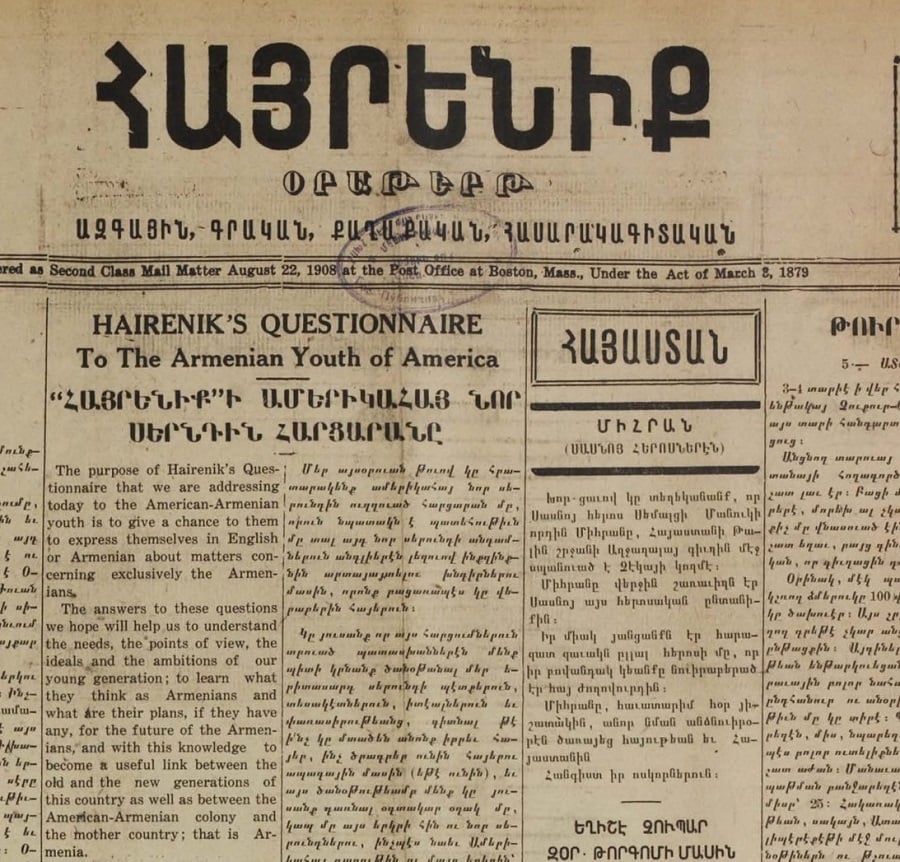

The Armenian Weekly. I have always found the term “diaspora” ironic. We embrace a simple label to describe an incredibly complex reality for the millions of Armenians who live outside the homeland in a vast array of host nations. Our hyphenated lives are indeed complicated as we navigate the retention of our core cultural values while integrating where we reside.

Density has a significant influence with this challenge. Our identity is manifested by our collective behavior. Many communities in North America were formed as a result of immigration patterns from the Genocide — others through more recent migration, such as the tragedies in Baku and unrest in the Middle East. Each entity has its own unique history and cultural norms but also retains certain common standards that enable connection to the global Armenian nation.

Our language is a primary example, as well as our faith and cultural practices. Some communities have declined due to local economic factors and assimilation while new ones have blossomed. Armenian communities in Florida, Texas and Las Vegas reflect demographic changes that impact our U.S. diaspora. Whether traditional or a reflection of new growth, the diaspora’s objective remains the retention of our faith and heritage. Virtually all of our infrastructure and programming is intended to encourage our survival through generational transition.

It is a formidable challenge that increases in complexity with the advance of a secular society, geographic dilution and the changing definition of “community.” Most of our churches and centers can no longer be defined as neighborhood facilities. Economic prosperity has altered where we live and its proximity to the “communities.” It is common today to drive 30-45 minutes to church, which impacts frequency of attendance.

Read also

Of course, there are exceptions. The Los Angeles Armenian community, with significant migration over the last 50 years, has been able to retain population density. The emphasis on primary and secondary schools has been a major differentiator and primary factor in identity retention. Despite the financial and attendance challenges, the results have been admirable. Thousands of young Armenians enter their adult life with the benefit of an Armenian education. With a large influx of Armenia-born residents, it remains to be seen what the rate of assimilation will be for the succeeding generations.

Immigrants born in Armenia have a unique sociological experience from the Soviet and early independence period. The midwest and east coast have relied more on the traditional Sunday and Armenian schools for education, with noble efforts and mixed results. Geographic distance and competing activities (e.g. sports, leisure and other interests) have marginalized many of these activities. Despite the remarkable dedication of teachers and community leaders, most of these schools have experienced decline in attendance over the last few decades.

What’s changed? Our concept of community has become less of a central component to the Armenian family, as compared to previous decades. From a social and religious perspective, our grandparents were less integrated into American society, but the current generation has significantly diversified its relationships, becoming less reliant on the “community.”

Aside from peripheral issues such as distance and logistics, the Armenian home has declined for many as the source of knowledge, commitment and role modeling. How many of us pray in our home or encourage language skills? Do we show the same parental role, modeling the sacrifice for our faith and heritage that we display for sports?

Community infrastructure cannot replace the importance of parental decisions. We must understand the long-term impact when we make successive short-term decisions. When we don’t like the results, it would be wise for each of us to start by looking in the mirror.

I feel very fortunate to have grown up as an Armenian in a small community. The warmth and family atmosphere were always magnets for participation. In our youth, we looked forward to seeing friends in Sunday School, AYF and into our young adult life. Of course, the downside of a small community is the limited availability of resources. We had to do certain activities with far fewer people and worked overtime to ensure a critical mass remained interested. Looking back, I believe that “living on the resource edge” encouraged innovation and creative thinking. I can’t say that I enjoyed having only five players for AYF basketball league games and getting consistently beaten by the larger chapters, but time filters what’s important, allowing us to retain the memories of fellowship, friendships and the values we acquired.

A small parish also offers incalculable opportunities. We would quickly learn how to work in the kitchen, organize events and pitch in to clean the hall. There was no job beneath us to keep the community functioning. With fewer resources to staff community infrastructure, opportunities such as teaching Sunday School, serving on the board of trustees or representing your parish at the National Representative Assembly (the Prelacy assembly) were encouraged. I was honored to serve as my parish delegate in my twenties. Participating in the proceedings of the Prelacy was an incredible learning experience. My first few years, I was more like a wide-eyed kid in a candy store, sitting with many of the men and women who were instrumental in the establishment and development of the Prelacy. I was a student of history, and being a small part of the proceedings was an honor.

During one of the Assemblies held in Detroit, one experience significantly influenced my thinking. A delegate from the St. Stephen’s parish, Michael Najarian Sr., was a close friend of my father’s. His home was always open to the AYF and became a social gathering place during regional activities. I had spent considerable time there, discussing church and national issues, and had a deep respect for Mr. Najarian. At the Assembly, the content was focused on religious and ethnic education within the church — on our successes and remaining challenges.

Mr. Najarian spoke of the threat of ignorance and our inability to impart useful knowledge in our educational systems. He used the term “functional illiteracy” to describe the result of our failures in the home and church infrastructure. Unless we were able to reverse this course, Armenians would continue to exit from the community , and many who remained would participate with limited functional knowledge. He was referring to knowledge of the history, customs, canons and protocols of the church that guide our participation. He also referred to the core experiences that instill love and identity.

His premise was that informed participants create the best results. With knowledge, you are free to form rational opinions and contribute to the diversity of our communities. The absence of knowledge among authority can be reckless and dysfunctional. His soliloquy, as expected, resulted in a vocal defensive posture from some delegates. Others applauded his transparency and directness. It is not clear what came of his offering that day, since there are visible signs of the accuracy of his prediction. From my perspective, it was an important inflection point in my approach to not only the church but community life. I have quoted Mr. Najarian countless times during seminars, lectures and other motivational and educational events with our emerging generations. It is one of the most profound statements on community identity I have experienced.

The diaspora in the U.S. has been in evolution. We must expect that the wheels will continue and the expectations of each generation will also evolve. What was critical to one generation may be less relevant to the next. This is why the current generation must empower the emerging one to have the freedom to lead. As the environment evolves, so must the generational management. Many have opined that our identity retention will remain robust as long as Armenians care and are committed. External resources are relevant but secondary. Identity is enabled through knowledge and a personalized connection.

In the diaspora, we struggle against invisible forces to retain our identity and many silently retreat into the fabric of the host nation. In Armenia, it is unconscious. The functional knowledge that is naturally absorbed in Armenia must be fabricated here through family and community. Even with a superb infrastructure, there are no guarantees of sustained identity, since it is always a personal choice. It would be sagacious for us to listen carefully to the new generation on how best to approach this ongoing challenge.