Mountains, create a breeze,

Find peace for my soul,

Take me to my home,

Take me home, take me home. – Lyoka

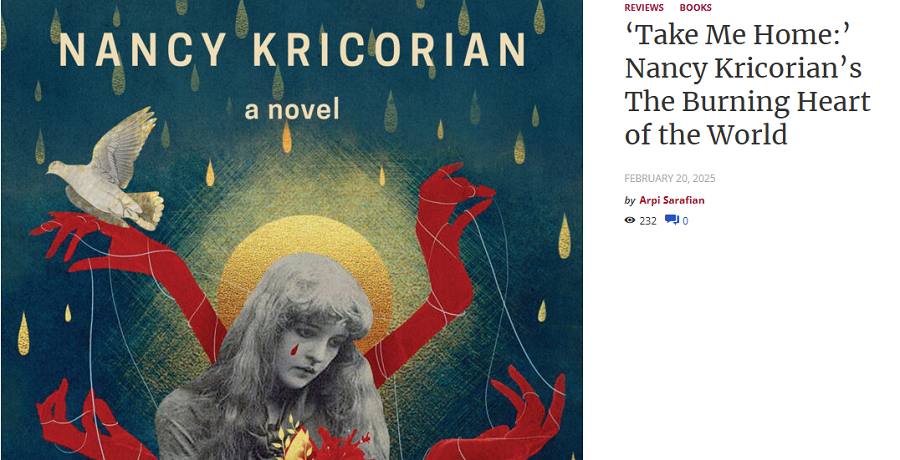

Even when the return is to unlivable conditions with no protection from any type of law, displaced people returning home is something to celebrate. The connection one has to one’s roots and the yearning to go back to those roots seems to almost define who we are. Much art has been inspired by the pain of the separation from one’s native land. The narrator in Nigoghos Sarafian’s The Bois de Vincennes, “homeless and alone” in an alien land, longs for the beauty and the truth that perhaps only one’s homeland can give. The speaker in Lory Bedikan’s poems knows that Mother’s Aleppo cannot be saved, even though going back to the “once upon a time” seems to be the only way out of the “hell” of their “new world.” It is the uniqueness of this connection that Nancy Kricorian brings to life in her latest novel, The Burning Heart of the World (Red Hen Press, 2024).

The Burning Heart of the World opens with the grandchildren dozing in their grandmother’s lap in the car on their way to the mountains in Lebanon. As a little girl, Medzmama had been driven out of her small Anatolian hometown of Hadjin, a town perched on the Toros mountains of Cilicia, in the Ottoman empire, following the mass deportation orders for Armenians from their millennia-old homes during the 1915-1921 Armenian Genocide. Medzmama entertains her grandchildren with stories of Gar ou chigar of a girl in Hadjin, named Sosi after the plane trees that were worshipped by Armenians since ancient times. Sosi loved nature. She loved the wildflowers, the trees and the animals of the forest. She especially loved birds which the Hadjintsis believed to have magical properties. Indeed, on the deportation route in the Syrian desert Sosi converses with the White Dove her grandma had set free after purchasing it at the market in Hadjin. And just as the bird had prophesied, the little girl survives the Death March and “lives to be an old woman with many grandchildren.”

These stories imbue the novel with the spirit of Armenian folktales which do, in fact, start with Gar ou Chigar, there was and there was not. “Through its folktales we can readily recognize the character of a whole nation,” writes Artashes Nazinian, director of the Folklore Section of the Armenian Academy of Sciences, in his Foreword to Leon Surmelian’s Apples of Immortality: Folktales of Armenia. Kricorian further invokes the magic and the spirit of the tales by ending her novel with the old Armenian legend, “Three apples fell from heaven, one for the storyteller, one for the listener, and one for the person who understands this tale.”

To tell her own story of displacement and exile Kricorian juxtaposes the 1970’s 15-year Civil War in Lebanon and the 2001 9/11 Twin Towers explosion in New York City. Questions such as, “Who are the terrorists?” “Why do they hate us?” prompt the reader to evaluate the desperation that leads to crazy acts of violence and to wars. The beautifully crafted 160 pages — in a 187-page novel — of the chapters “New York City” and “Beirut” describe the disruption caused to the lives of the characters by the bombings and the rocket attacks. Yet, the ten pages on “Hadjin” that conclude the novel provide something that goes deeper than the surface narrative.

In the “spare economical style” of our folktales, Surmelian might say, Kricorian evokes the tragedy and the loss of Hadjini Joghovourtin Badmoutioune. She also captures the spirit of goodness of a whole culture with her colors and vivid images. Sosi’s mother, known for her fine breads and pastries, bakes Hadjin’s traditional sweet bread for Easter, “using butter, white flour, yeast, and sour cherry seeds she ground with a brass mortar and pestle.”

Kricorian’s, “As the spring progressed, different wildflowers appeared, starting with the blue and white glory-of-the-snow, followed by the purple crocus, the carpet of scarlet poppies, the star-like blossoms of the asphodel, bright yellow buttercups, tiny forget-me-nots, and many more,” tells us why Hadjin will “always remain our beloved homeland.”

The whole notion of home is complicated. When exile has become “closer to a norm,” to borrow the words of the late Edward Said, writers creating in exile sometimes see the crossing of borders and living across boundaries as an advantage as it helps them gain a new perspective with which to rediscover the world they left behind. The idea of cosmic alienation, on the other hand, makes the very concept of “home” irrelevant. As William Saroyan, Peter Najarian and numerous others have iterated, the world may just be “one large foster home” and one may always be “far from home.” Nonetheless, in its simplest basic sense of physical separation from one’s homeland, exile remains a condition to be shunned. When confronted with the option of going from “this madhouse,” Lebanon, to America, in other words, when confronted with the option of being displaced once again, “Exile is a burning shirt I will never wear again,” Grandma tells her granddaughter Vera who “do[es]’nt want to go” to America either.

The connection one has to one’s native land impacts one’s well-being as it implies something more than just the immediate concerns of day to day survival. Arguably, Medzmama could have lived a peaceful life in Hadjin, happy forever after, while the life of her granddaughter Vera in a future of permanent exile remains, at best, unpredictable.

Kricorian understands the craziness of uprooting people and of scattering them around the world. She also understands the spirit of the grandmother which believes in the magic of the birds of the desert that protect and watch over her and her family in all calamities. Even on the deportation route, in her burning heart, Sosi could be fascinated by the beauty of the gray Wallcreeper, her favorite, hopping and fluttering across the rocks and the cliffs on the side of the road.

All of Kricorian’s novels — in addition to Burning Heart, Zabelle, All the Light There Was and Dreams of Bread and Fire — explore the post-genocide Armenian diaspora experience and the connection one has to one’s culture and history.

The book is available at Red Hen Press, Bookshop.org and Barnes & Noble.