The Armenian Weekly

She looked deep into the girl’s eyes. “They’re not servants. You—you and I both—need to stop calling them that. They were slaves. My husband set free his family’s slaves.”

“Them’s just words.”

“Yes. And words have meanings.”

—From Chris Bohjalian’s The Jackal’s Mistress

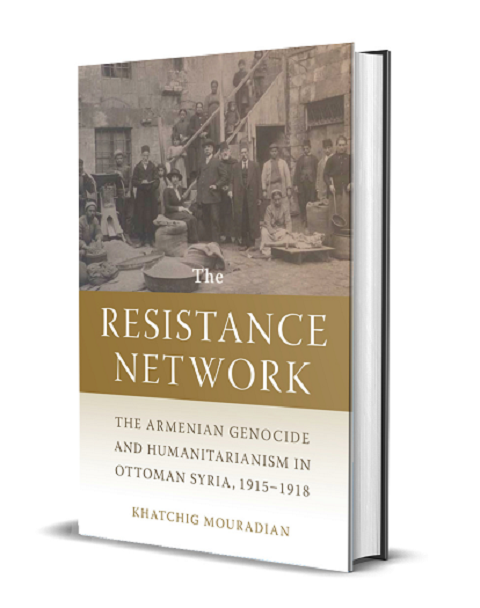

On March 11, New York Times bestselling author Chris Bohjalian kicked off his 35th book tour with his 25th novel, The Jackal’s Mistress. The book launch was held at the Armenian Museum of America in Watertown, Massachusetts, a location that holds great meaning to both Bohjalian and the community. Joining him was Khatchig Mouradian, a historian, educator and author whom Bohjalian calls his “godfather and moral compass”—not to mention, his dear friend and traveling companion.

During his introduction of the evening’s program, executive director Jason Sohigian shared an anecdote that commonly occurs at the museum. On the first weekend the museum reopened after the pandemic, a group of women from Salem, Mass. visited after reading The Sandcastle Girls in their book club, intrigued to learn more after reading about the museum in the book. “We’re really proud that Chris honors his Armenian roots and speaks out often about our history, human rights violations and genocide that continue even to this day,” Sohigian said.

Read also

Bohjalian and Mouradian took the stage in front of a capacity crowd, surrounded by Tigran Tsitoghdzyan’s stunning, hyper-realistic paintings in the museum’s contemporary gallery. It was publication day for The Jackal’s Mistress, set during the Civil War, with two main characters on opposite sides of the divide. The novel begins with a harrowing scene introducing Libby Steadman, a Southern woman determined to survive until her husband returns from the war. Soon after, she discovers Captain Jonathan Weybridge, a Union soldier gravely injured in battle, and she must decide whether to help him or leave him to die alone.

Bohjalian describes the novel as “a Civil War Romeo and Juliet… While I was in Richmond, Virginia, I thought to myself, ‘If ever there was a time when our country needs a book that shows how two wildly disparate political opinions can find gentility, peace and make the right moral decisions, it’s now.’ And so, I tried to write a book about a Virginian and a Vermonter who find a way to transcend the carnage of the Civil War, in the same way that I hope our own nation can find a path forward in 2025 that isn’t about meanness, stupidity, pettiness and cruelty.”

The lively evening covered various topics, from changes in publishing and the importance of truthful journalism to Bohjalian’s extensive book tours and research process. Mouradian reflected on Bohjalian’s influence, praising him as an inspiration for readers, booksellers and the broader community. “Beyond that, he is a wonderful person with whom I’ve had the privilege of traveling and doing events such as this. Thank you, Chris, for being that wonderful person.”

Bohjalian took the opportunity to encourage support for independent booksellers. He praised the good folks from An Unlikely Story Bookstore & Cafe, who partnered with the museum for the event. When it came to journalism, Bohjalian shared that he had spoken with the Armenian Weekly earlier in the day and was a fan of reading the print newspaper “on Saturday afternoons in the bath in the winter.”

Bohjalian regaled the audience with stories from his very first book tour, saying, “Everyone in the house was related to me by blood.” He shares his penchant for using dread to retain the reader’s interest, joking, “Dread is my jam.” Bohjalian also noted that it’s likely in his DNA, since “a lot of us in this room have multi-generational trauma inside us.”

Mouradian praised Bohjalian’s impeccable and thorough research for his novels. The author shared that while he has traveled to nearly every location associated with his books, he has never been able to visit Aleppo, Syria, due to the ongoing conflict there. Earlier in the evening, Mouradian had discussed research for historical fiction with Victoria Atamian Waterman, author of Who She Left Behind and Weekly columnist, who was also in the audience and noted by Bohjalian.

Bohjalian stressed the importance of historians, stating, “Novelists who write historical fiction need historians. And Khatchig’s job is much harder than mine because he can’t make anything up. It is the opportunity that people like Khatchig give me to go back in time and make it accessible in the present.”

Mouradian pointed out that Bohjalian has written plays, and several of his works have been made into movies. When asked about using these formats to reach new audiences, Bohjalian said, “I don’t view that so much as engaging with my audience directly as trying to tell a story that someone’s interested in. I’m writing it because it’s the story that I feel needs to be told or my soul wants to tell.”

The Jackal’s Mistress is a story that needs to be told. Immediately, readers will be immersed in the narrative and, as with all of Bohjalian’s books, invested in the characters. The book is thrilling and suspenseful, with detailed descriptions that appeal to the senses. This reader highly recommends Bohjalian’s 25th novel, another masterpiece in his prolific career!

Prior to the event, I had the pleasure of talking with Bohjalian for the Weekly. Following are some excerpts from our conversation.

Pauline Getzoyan (P.G.): Was it a conscious decision on your part to have a book set during the Civil War as your 25th?

Chris Bohjalian (C.B.): No, my 25th book could have been any of a number of topics. I must have at least five or six completed manuscripts I never published, or partial manuscripts, so the idea that I’m writing about the Civil War is just good fortune that it happens to be an important symbolic number.

P.G.: How has your writing process changed from the beginning? Also, I remember you talking about opening the gigantic dictionary that you have in your office every day and selecting a new word that you’ve never used before to use that day in your writing. I find that to be a lot of fun, as a reader of your novels. Are you still doing that?

C.B.: Because I’ve been writing since the Mesozoic era, I have muscle memory. And it is much easier for me to write a novel now than it was 10 or 25 years ago.

One of the things that is not unique to me, but I think is happening with all artists right now, is that we are in the midst of a post-pandemic renaissance. This is going to sound like a humble brag or a not humble brag. Since March of 2020, I finished Hour of the Witch. I wrote The Lioness. I wrote The Princess of Las Vegas. I wrote The Jackal’s Mistress. I wrote my 2026 novel, The Amateur, and I wrote a play called The Club. And I’m not unique. When I look at the work that, for example, my wife [Victoria Blewer] is doing as a visual artist, when I look at friends of mine who are novelists and playwrights and how productive they have been, I am really quite impressed. And we’ve seen this before. After the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920, we had a spectacular literary renaissance, and we are in the midst of that again right now.

For example, in a three-month period, three Armenian Americans are publishing three novels: Aram Mrjoian’s Waterline, Nancy Kricorian’s The Burning Heart of the World and The Jackal’s Mistress. I’m sure there have been other times when three Armenian American novelists published three novels within three months, but it has to be rare.

And yes, I still have a dictionary the size of a Mini Cooper in my library. I still try to pick out a word or two or three that I will try to incorporate that day. I do not always succeed, because sometimes you just can’t use the word “luminescent” without sounding like an idiot. But for a book like The Jackal’s Mistress, I was immersed in Civil War slang and Civil War verbiage, for example “gallinippers.” When I came across “gallinippers,” which are very big bugs, I knew I had to incorporate it into the book.

P.G.: You’re very descriptive in your writing, which is one of the things that I love about it. It also explains why television, movie and theatrical producers would be interested in your work—besides the amazing stories and writing—because the descriptions are just incredible.

C.B.: The thing about the Civil War that I find really interesting is how close everyone was to understanding how to make a leap forward scientifically, but they weren’t quite there yet. We talk about how many soldiers and how many civilians died of infectious diseases, because we didn’t understand infectious disease management. But they did know something. For example, infantry men would know that coffee tasted bad when they were making it from water downstream from the cavalry. So they tried not to, but they didn’t understand that one of the reasons why the water was putrid was because it was going to make you sick.

It’s really important when you’re writing a novel, though, not to show off that you’ve done your homework. With historical fiction, it’s a balancing act because you need to immerse your reader in that moment in time, but you don’t want to show off and say, “Look what I know!” or “How interesting is this?” It might be really interesting to me, but is it going to slow the narrative?

When I was writing The Sandcastle Girls, there were two factors always on my mind. The first is absolute rage. And the second is that most people reading this book have no idea where Aleppo is or who, for example, Jesse Jackson was, or why there might have been an American Consulate in Aleppo. So, how do you share that sort of detail with the reader without slowing the narrative? Sometimes you do it via shock, and I did that in both The Jackal’s Mistress and The Sandcastle Girls. In an early scene in The Jackal’s Mistress, Libby Steadman is attacked by a drunk marauder, because I wanted readers to understand instantly that fundamentally she is a woman alone in a world where women are still the spoils of war. In The Sandcastle Girls, the very first thing that the American woman, Elizabeth Endicott, sees when she arrives in Aleppo are gendarmes beating Armenian women who are naked, sunburned, starving and dying as they are marched into the quarter.

When I write historical fiction, my goal is for readers to get a sense of its contemporary relevance. That was true in The Sandcastle Girls, true in Hour of the Witch, and certainly true in The Jackal’s Mistress. This book really began for me in 2022 when I was in Richmond, Virginia. I’d written about the true story that inspired this way back in 2003, but I didn’t see a novel in it until 2022. In a place like Richmond, you really feel the weight of history and the weight of the Civil War. I thought of that article I’d written 19 years earlier, and if ever we need a novel that shows a path forward for the North and the South—for people who are spectacularly divided—it is now.

I see so many parallels between The Sandcastle Girls and The Jackal’s Mistress because they’re both love stories, set in a moment of cataclysm, between two people who are really lonely. They are both love stories in which the principal people—in the case of The Jackal’s Mistress, both—have somebody else, in theory, in their lives, and in The Sandcastle Girls, Armen is, of course, looking for Karine.

P.G.: Do you plan to write another novel with either an Armenian theme or an Armenian main character who drives the story?

C.B.: I do. But when this book tour is done, I’m really interested in toying with my vision for a one-woman play based on The Sandcastle Girls. A few years ago, I saw the great actor Carey Mulligan in a one-woman play in Manhattan. It was epic, and I’ve thought about it so much. I realized that the play stayed with me because of what an actor was able to accomplish with a combination of a brilliant, kaleidoscopic set and projections.

The Sandcastle Girls is fundamentally two stories: the story of Laura Petrosian and the story of her grandparents, Elizabeth and Armen. Since Laura is telling the story, is it possible for Laura to be a magnificent storyteller holding the audience in the palm of her hands while she shares this visit to Watertown, seeing a photograph and realizing it has something to do with her family? I think there’s a way to do that. So, I think that’s my next project. Can I figure out how to make a magnificent one-woman play out of The Sandcastle Girls?

P.G.: What can you tell us about your next novel?

C.B.: It’s done. In August of 2026, you will see a novel called The Amateur, set between 1978 and 1980. It is about a spectacular young female golfer who has the LPGA in her sights. At 18, just before leaving for Yale, she accidentally drives a golf ball through the practice net at a swanky country club outside New York City, instantly killing a young caddy and classmate, completely derailing her life.

And here is the best part of this novel: it’s narrated by a 60-something female novelist, known best for writing a book about a midwife on trial for manslaughter. It is the most weirdly autobiographical, meta novel ever. Readers who know me and Victoria will find an Easter egg in every chapter.

Victoria, my editor Jenny Jackson and my daughter Grace Experience all read the first draft, and they all said the same thing, essentially: this is one banger of a novel. My editor said, “I have never seen a first draft this tight ever.” My agent, my editor and Victoria all got it on the same day, and read it within 48 hours. It’s a novel about class, about older predatory men, about how young women are doxed and slut-shamed, and it is a novel about grieving for a suddenly dead child. All of it is in that book.

P.G.: I can’t wait!

Pauline Getzoyan

Main Photo Caption: Chris Bohjalian and Khatchig Mouradian in conversation in front of a rapt audience