by Arpi Sarafian

When Turkey is not held accountable for its perpetration of the 1915 Armenian Genocide and when Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey, enjoys absolute impunity over its systematic destruction of the Armenian cultural and historical heritage in Artsakh — ethnically cleansed of its indigenous Armenian population in a lightning attack in September 2023 after a nine-month-long blockade — it becomes easy to decry, perhaps even to deride, the effort by international teams to monitor the Armenian religious and cultural heritage of Artsakh, or the endeavor to come up with yet another document to “prove” the veracity of the calamity that befell the Armenian people in 1915 at the hands of the Ottoman Turkish State. Nonetheless, providing evidence that would contradict Turkey’s ongoing denial of the Genocide remains extremely important.

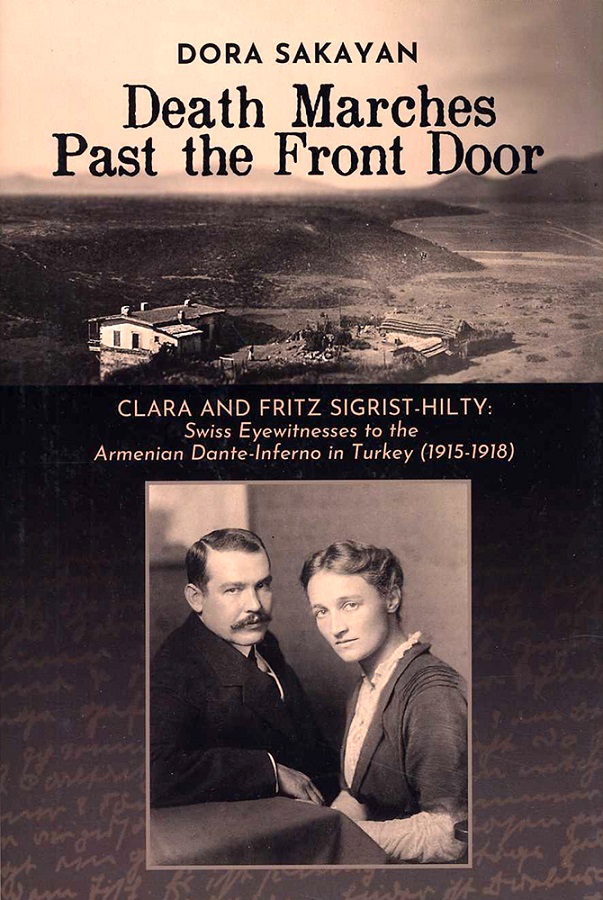

Dora Sakayan’s Death Marches Past The Front Door (Fresno University Press, 2023) furnishes one such documentation. The book is based on the diary the newly-wed Clara Sigrist-Hilty, a Swiss citizen, kept in the years 1915-1918 she spent in Turkey with her civil engineer husband, Fritz Sigrist-Hilty, contracted to build the Berlin-Baghdad Railway that was to connect Europe with the Persian Gulf. Clara’s diary provides a three-year testimony of the “death marches” the couple witnessed daily from their cottage perched on a steep hillside in Keller, a small Kurdish village in the Amanus Mountains, located in the midst of the deportation routes to the Syrian desert.

Read also

“Armenians continually pass by our house,” writes Clara on August 10, 1915. Numerous entries describing the deportations follow: “ Columns of deported Armenians,” “Endless successions of deported Armenians,” “The flood of Armenians doesn’t stop,” “We hear now that all Armenians should be gone from Adana.” Clara is increasingly uncomfortable. Her indignation at “the bleak fate of an entire people doomed to destruction” and her “anger at this abominable country” are palpable. On June 16, 1916, she writes: “You feel crushed facing this human misery, and only one thought prevails: Get out from this hideous country!”

Sakayan’s expertise in German — she holds a Doctorate in German Philology from the Moscow Lermentov State University — and her scholarly interests in both German and Armenian Studies — Sakayan has written extensively on the Armenian Genocide — put her in a unique position to decipher the now extinct East German script of Clara’s Diary. It was Sakayan’s passion for the material that enabled her to undertake the painstaking task of revealing the significance of the diary to the world. The meticulously researched Death Marches Past The Front Door offers a wonderful interplay of primary and secondary sources. Sakayan’s details and comments — always generous, always appreciative — never bore.

Death Marches Past The Front Door comprises three sections. Each section provides biographical information and a detailed account of the arduous process of bringing the contents of the original manuscripts to their publication. Part I presents Clara’s diary, a day-by-day record of “significant” events — “On a small hill, the Armenian church, which was visible from everywhere, is now a field of rubble. All Armenian houses are deserted” — interspersed with “insignificant” occurrences — the couple’s daily walks up the hill, cultivating the garden, entertaining the many friends they had — and the 15-page Memoir, “Summer 1915,” Clara wrote after she returned to Switzerland.

Part II includes three essays by Fritz about his experiences in Turkey. “Clarli’s innumerable tears and my desperate fears will always be stuck in our memory,” writes the compassionate Fritz who was always in despair over being unable to adequately help his “Armenian Friends,” the workers so indispensable to the construction of the Railway.

Part III offers excerpts from The Armenian Dante-Inferno, the 1970 memoir published in Beirut, Lebanon, of Haig(azun) Arman Aramian, Fritz Sigrist-Hilty’s storehouse manager in Kettel. Although written 50 years later, Aramian’s accounts of his “miraculous rescue” by his Swiss masters and of the atrocities he witnessed — “Hundreds of volumes would not suffice to record all the details of the martyrdom suffered by Armenians in the years 1915-1918” — corroborate Clara’s Diary and further confirm it as irrefutable evidence of the cruel reality. Nothing I have read on the Genocide, fiction or nonfiction, has impacted me as profoundly as the “I see,” “I hear,” “We hear of,” “They talk of” of the entries in the Diary.

In October 2016, Sakayan went to Switzerland for a book tour of her They Drive Them into The Desert (Limmat Verdag, Zurich), the German translation of the Sigrist-Hilty testimonies. In a letter she circulated on November 5, 2016, titled “100 Years After . . . ,” the ecstatic Sakayan describes the “sensational” book launch and her “great reception” in Switzerland as “an expression of the love of the Swiss for all the Armenians in the world.” “Yes, once again I recognized the Swiss as loyal, appreciative, and hospitable people,” she writes.

Sakayan’s book acquires even more significance in the context of the skepticism of traditional historians regarding personal accounts as trusted historical sources. As noted by Dr. Bedross Der Matossian, author of the highly acclaimed The Horrors of Adana, at this year’s annual UCLA April 24 Commemorative Lecture, extending the documentation beyond State archives to include eyewitness accounts, letters, memoirs, diaries gives us insights into the broader truth. It helps us better understand what happened and why it happened. To illustrate, Der Matossian cited the importance of exploring Catholicos of the Greater House of Cilicia, Sahag II Khabayan’s correspondence with Ottoman officials, European diplomats and Armenian leaders as documents that contradict Turkey’s denialist approach to the Genocide. While recognized and respected, the methodology is still to find its place in Armenian Genocide History, averred Der Matossian.

Indeed, Clara’s testimonies of the atrocities, embedded in her recordings of the “blooming magnolia tree,” the ”radiant morning,” “wonderful sunset,” or “joy at the many seabirds,” make one ponder human nature and the suffering of the world. I see the Diary as a desperate cry to reclaim our humanity. “We can no longer look at the refugees passing by . . . You feel crushed facing this human misery,” confides Clara (italics mine).

In a recent interview on CivilNet, in Yerevan, pioneering Turkish historian Taner Akçam referred to the Armenian Genocide as a “widely established fact.” “It is no longer both sides of the issue with Genocide treated as an opinion,” he affirmed. Which is not to say that the Turkish government has stopped denying the Genocide. “But their language has changed,” noted Akçam.

The voice of truth will ultimately be heard. Remembering is key. Pursuing our efforts is paramount. Sakayan’s probe into the Armenian Genocide from the perspective of the Sigrist-Hilty couple is an important contribution to that effort.

Featured in the book are numerous photographs of Fritz and Clara and of Sakayan and Aramian, photographed with Clara’s extended family during their visits to Switzerland, bring the reader closer to the Swiss couple and add immensely to the book’s appeal.