By Harut Sassounian

The Armenian Genocide Research Program (AGRP) within The Promise Armenian Institute at UCLA launched last week a ground-breaking project enabling Armenians to seek restitution of their properties confiscated by the Turkish government during and after the Genocide.

In addition to the mass killing 1.5 million Armenians, the Turkish government occupied their homeland of Western Armenia and seized their properties. Thanks to the UCLA initiative, for the first time all the missing information is gathered in a single depository.

Read also

During a June 16 webinar, Prof. Taner Akcam, AGRP Director, shed light on the systematic expropriation and redistribution of Armenian wealth during and after the Genocide, described by the Turkish government as ‘Abandoned Properties’ (Emval-i Metruke).

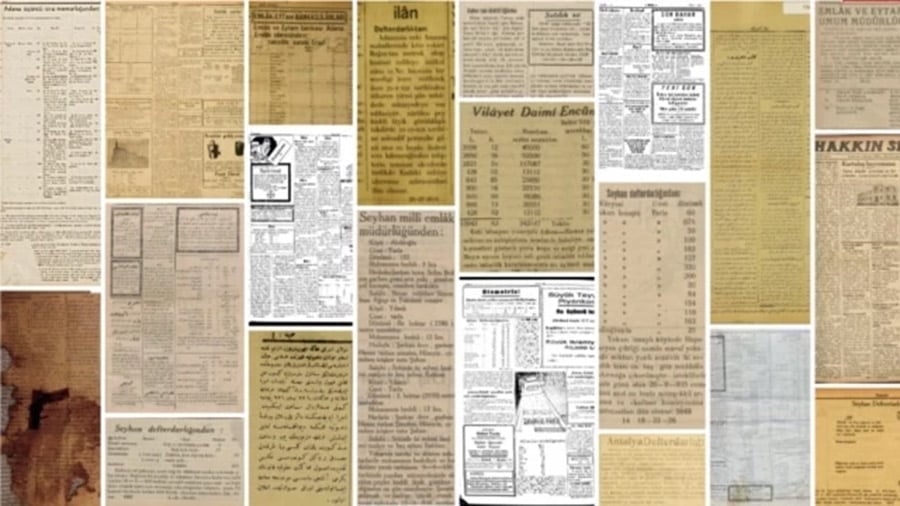

Independent Turkish researcher Sait Cetinoglu spent years collecting the government’s auction notices for these properties which had appeared in local newspapers across 34 Turkish cities and towns in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Cetinoglu has turned over these notices to UCLA which has digitized and translated them from Ottoman Turkish into modern Turkish and English. They are available at: www.international.ucla.edu/armenia/stolenarmenianproperties.

In a comprehensive 31-page report posted on the UCLA website, Cetinoglu and Akcam detailed the Turkish government’s contradictory and deceptive orders for disposing the confiscated Armenian properties: “an official order was issued on May 27, 1915, and the widespread seizure of Armenian property followed shortly thereafter. On May 31, 1915, the Ottoman Council of Ministers issued a decree formally regulating the ‘confiscation’ of Armenian assets, followed by a more detailed 34-article decree on June 10. Throughout the summer, special circulars were sent to various provinces, culminating in a formal law on September 26, 1915, and an implementation decree on November 8 of the same year. These laws and decrees stipulated that all movable and immovable Armenian assets must be recorded in official registries and their values be allocated to Armenians in their new settlements…. [However], a 1918 report by a joint commission of the Ottoman Ministries of Justice, Finance, and Internal Affairs explicitly stated that not a single Armenian had been compensated for their confiscated properties. In effect, the Ottoman state became the principal beneficiary of the plunder, using these assets and the proceeds from their sales to fund various state institutions.”

Cetinoglu and Akcam explained that after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, the newly established Turkish Republic “assumed control over much of the remaining Armenian property. However, the fledgling state faced significant financial challenges. As a result, beginning in 1923, various state institutions began auctioning off these looted Armenian properties. Official notices of these sales were regularly published in local Turkish newspapers.”

For example, a notice in the Diyarbakir (Dickranagerd) newspaper on Sept. 14, 1931, announced that an auction will be held on Sept. 17, 1931 for a house registered in the name of Hatun (Khatun), daughter of Ohan, in Ali pinar village, sold to Sheymus (son of Ahmet) of Kara Kilise refugees, for 20 Liras.

It is estimated that the total confiscated Armenian properties, including hundreds of thousands of homes and buildings, factories, mines, over a million acres of land, vineyards, olive groves, mulberry gardens, around 2,500 churches, and 1,000 schools, are now worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

The confiscated Armenian properties were distributed to various Turkish entities. According to Cetinoglu and Akcam, “just as in the period of the Committee of Union and Progress,” the Republic of Turkey transferred some of these properties “to companies in order to develop a national industry and a Muslim bourgeoisie, and some of them were allocated to the Republican People’s Party — the only party of the period…. Many real estate properties were distributed, according to need, to various institutions such as associations, state institutions, municipalities, chambers of commerce, industry, and agriculture, the Red Crescent, and banks. In short, it could be said that every segment of [Turkish] society benefited from Armenian properties.”

During the Kemalist period, the confiscated Armenian properties were distributed as follows:

- “Sale and land distribution to Muslims”;

- “Allocation and sale to immigrants (muhacir)”;

- “Transfer and allocation to state institutions”;

- “Allocation to the military”;

5 “Allocation and leasing to banks, the Chamber of Commerce, and the commodities exchange”;

- “Sale to companies”;

- “Allocation, leasing, and sale to institutions linked to the regime, such as the Turkish Hearth, the Red Crescent, the Teachers Union, and the Trabzon Sports Club”;

- “Allocation to the families of Unionist leaders” who were murdered by Armenians, such as Talat and Cemal Pashas, Cemal Azmi, and Bahaeddin Shakir, according to a law adopted by the Turkish Parliament on May 31, 1926.

It is now up to the Armenian community to take this valuable information compiled by UCLA and file lawsuits against Turkey in U.S. federal courts demanding just compensation for the confiscated Armenian properties.

As I wrote last month, Armenian-Americans should urge the U.S. Congress to pass a law to be signed by the President of the United States enabling lawsuits against the Republic of Turkey to receive compensation for the confiscated properties. This new law would allow Armenians to file lawsuits long after the Statute of Limitations has expired.

U.S. courts could issue binding judgments against Turkey to pay restitution to Armenians for their losses. If Turkey refuses to comply, the courts could then order the confiscation of all Turkish government-owned assets in the United States, such as buildings, bank accounts, and planes belonging to Turkish Airlines.

UCLA, as an academic institution, has done its part of compiling this valuable list of the Armenian confiscated properties. It is now the Armenian community’s turn to initiate legal actions to seek full restitution from Turkey.