If You Don’t Believe, You’re Afraid

In 1931, German philosopher Karl Jaspers warned that, alongside technical progress and the emergence of a universal order of human existence (what we would now call globalization), a new kind of consciousness had developed—one rooted in constant anxiety, even fear of losing everything. In short: fear of life itself. Humanity, he said, lives in a state of constant tension, struggling to withstand competition. As one example, Jaspers noted that people fear being cast aside by society once they reach the age of forty.

This fear is closely tied to the desire to keep up, to have influence, to belong. And from this anxiety, Jaspers argued, the nature of the modern state emerges. “When the state was endowed with the authority of legitimized divine will,” he wrote, “people submitted to the decisions of a minority and tolerated what was happening, believing it to be guided by providence. But today, people have come to realize that the actions of the state no longer reflect a divine will binding for all. Instead, they see it as the manifestation of human will. And participation in that will has become the goal of every individual.”

Although Jaspers wrote this nearly a century ago, his observations proved relevant both in the long arc of history and in the events that followed just two years after he published the book. In that moment, the “mass man” found a “superman” who took upon himself the responsibility of directing the masses. Once that happened, there was no longer any need to fear—or even to think.

Read also

Later, this fear of real life began to disguise itself as “free will.” In the absence of a solid, or in Jaspers’ terms, “substantial” meaning, life became a race—for success, money, positions, pleasure, and entertainment. Many people now scoff at the notion of “divine will.” And human will, by contrast, is so fragile, subjective, and—let’s say—competitive, that everyone feels entitled to enter the arena and leave their mark: as an expert, as a “cool guy,” or as a “representative of the people.” But this doesn’t eliminate fear. On the contrary, it fuels it: the constant anxiety that someone will be more successful than me, or will have more sweet fun than me. A better expert, a cooller guy, a more “authentic” representative of the people. Maybe even a better Christian.

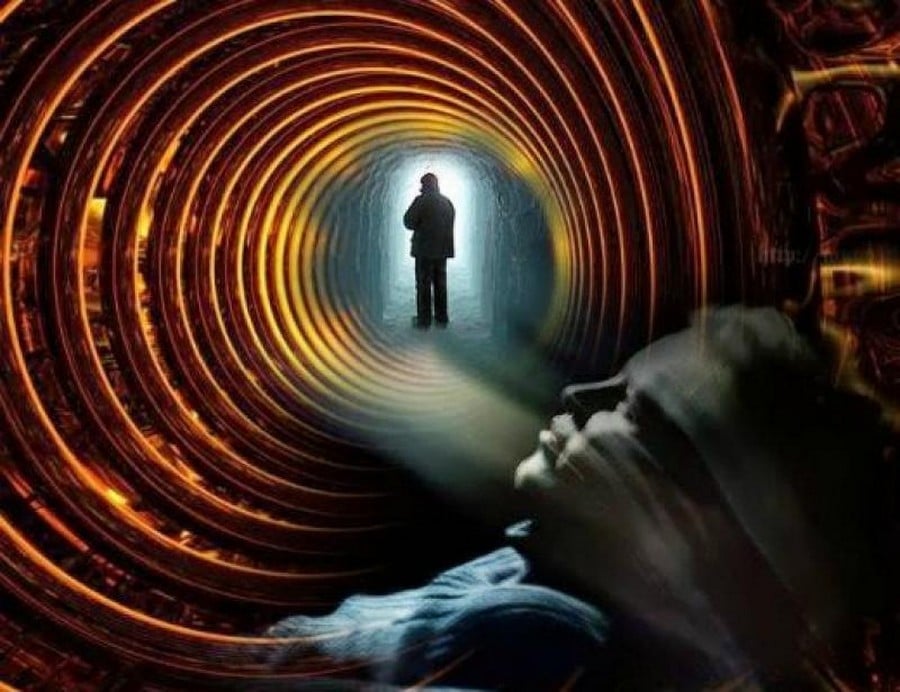

This is the fear of those who lack real faith. It’s a familiar condition: either you’re afraid, or you believe. Either you crave the approval of others—and live in fear, because that approval is never complete, never universal, never permanent—or you serve your ideas, your principles, your God.

But there are rare individuals who possess a strange and dangerous trait: they believe they embody divine will. That is, in the world we know, there is human will, there is divine will—and then there are pathological figures suffering from delusions of divine authority. They are neither apostles nor prophets, but (forgive the expression) imagine themselves the incarnation of God.

False prophets have existed since the time of Jesus. But in the age of mass consumption and social media floodwaters, these “prophets” increasingly resemble people who, at first glance, show no signs of prophecy at all.

Such people do not end well.

Aram ABRAHAMYAN