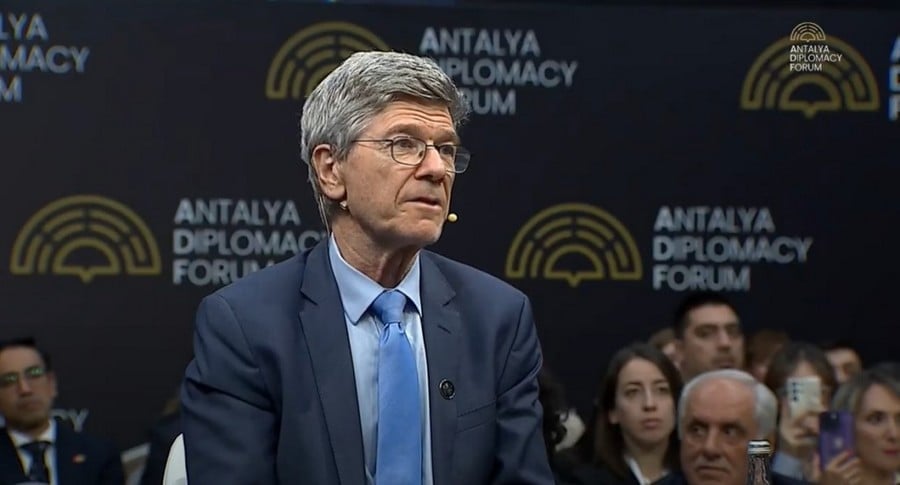

Jeffrey Sachs explains

I listened with real interest to Jeffrey Sachs’s interview with 168 Hours—the colleagues did an excellent job. I haven’t noticed whether Armenia’s social media space has labeled this Columbia University professor and world-renowned economist a “Russian slave” or “Putin’s stooge.” Given the intellectual level of today’s official propaganda, such labels are entirely possible. But I would advise anyone unprejudiced to listen to the interview.

Jeffrey Sachs is a proponent of realism in international politics. What does that mean? Take, for example, our relations with Azerbaijan. If you say that peace with our neighbor should have been achieved through negotiations (the last real chance was in 2019), then you are a realist. If, however, you claim that suffering a military defeat brought us a better result than any negotiated settlement could have, then you are not only ignoring the lessons of millennia of history—you are also living in strange fantasies, or worse.

I first heard Sachs in February this year, when he spoke at the European Parliament. For us it may sound unusual that an American professor would so sharply criticize his own government’s policy. In Armenia, a YSU professor making similar remarks about Pashinyan’s government would be fired at once. (Here, people risk trouble even for pressing the “wrong like.”) But whatever else one says about the United States, freedom of speech and academic freedom are respected there.

Read also

The highlight of Sachs’s address at the European Parliament was his call for Europe to pursue policies independent of Washington and to normalize relations with Russia. What the United States and Europe had been doing in Ukraine since at least 2014 (“Maidan,” etc.), Sachs judged not only wrong but a path that inevitably led to war. Most striking was his account of a one-hour conversation, two months before Russia’s invasion in February 2022, with President Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, where he tried to persuade him to prevent war.

Here I cannot resist a parallel. Can anyone imagine an Armenian professor calling Security Council Secretary Armen Grigoryan—or any Civil Contract official—and trying to convince him of something? Even if such a conversation were conceivable, the CP would dismiss the professor outright, insisting they already know everything, and then post on Facebook about how some “rotten fifth columnist” dared to lecture them.

According to Sachs, the exchange with Sullivan went like this:

Sachs: “Stop Ukraine’s NATO membership.”

Sullivan: “Ukraine will not become a NATO member.”

Sachs: “Then announce it publicly.”

Sullivan: “We can’t say it publicly.”

Sachs: “If this continues, war is inevitable.”

Sullivan: “There will be no war.”

Like all realists, Sachs deals in calculations—not in moral categories of who is good or bad, who embodies global “good” or “evil.” In his interview with 168 Hours, speaking as an experienced lecturer, he explained it all in simple terms, “on the fingers.” The US is Iran’s enemy. By ensuring an American presence on the Iranian border (and for 99 years), Armenia puts itself and regional stability at risk. Israel and Azerbaijan are allies, which means Armenia is being involuntarily dragged into the Israel–Iran conflict. Peace, Sachs argues, must be established with our neighbors—without involving a power located tens of thousands of kilometers away. (A similar concern, though expressed more cautiously, appeared in Zhirayr Liparityan’s article, which, I believe, was unfairly attacked with excessive harshness.)

It is not easy to respond to Sachs’s arguments with objective counterarguments. It is only easy to dismiss them with empty “social media” chatter.

Aram ABRAHAMYAN