In my teenage years, we admired the football players of Ararat-73, above all Eduard Markarov and Arkady Andreasyan. But it would never have occurred to us to weep with joy or faint if we saw them. Even if we had seen Pelé, we would not have been moved to such an extent. There was none of today’s frenzy around footballers—no bodyguards, no “selfies,” and the like.

At roughly the same time, there was fanatical devotion to, say, Elvis Presley or the Beatles—at their concerts, teenage girls would fall into hysterical ecstasy in the stadiums. (But I can hardly imagine Glenn Gould or Wilhelm Furtwängler provoking such emotions.) Mass ecstasy often arises when form—broadly speaking, the show—takes on greater importance than content. And in the 20th and 21st centuries, all this has been accompanied by an aggressively noisy information environment.

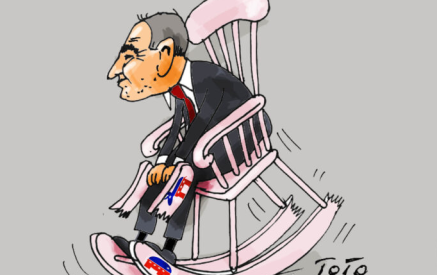

Showmen, as a rule, also succeed in politics. The classic example is Donald Trump. Let us leave aside the episode that concerns us, when he was heroically “reconciling Aber-Bajan and Albania,” aspiring to a Nobel Prize. About two weeks before the signing of those “historic documents,” Trump and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen also concluded a “historic deal” in Scotland: customs duties on EU goods would amount to 15 percent—whereas earlier Trump had threatened 30 percent. In return, the EU undertook to buy military equipment and energy resources from the US worth 750 billion dollars and to invest another 600 billion in the American economy.

It is highly unlikely that this deal will ever materialize.

Read also

But that is not the point. The point lies in the photographs, the handshakes, the smiles, the information buzz. The deal concluded in Scotland is about as realistic as Armenia’s national football team becoming a World Cup medalist in 2050. But the main thing is to announce such a “goal” publicly—preferably in a stadium—and to extract thunderous applause in that moment. What follows afterwards interests very few people.

…Ronaldo is, of course, a great master of football. What he has achieved in terms of money and fame is, as they say, “well deserved.” The problem is not Ronaldo, nor even the exaggerated emotions he evokes. The problem is the atmosphere created worldwide, when real events, real people, real problems are replaced by the simulacrum—by the photograph, the image, the imitation, the illusion, the avatar.

Aram Abrahamyan