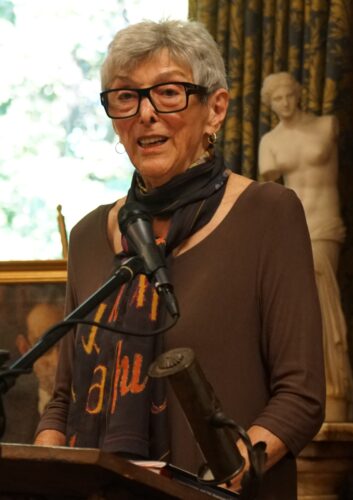

ARLINGTON, Mass. — Author and educator Muriel Mirak-Weissbach, on September 28, presented her most recent book, A German General and the Armenian Genocide: Otto Liman von Sanders Between Honor and State, at the Armenian Cultural Foundation.

About 100 people attended the program, co-sponsored by the Tekeyan Cultural Organization, the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research, Berghahn Publishing and the Goethe-Institut Boston.

Her subject, General Liman von Sanders, led the German military forces in the Ottoman Empire. Since his death, his name has been maligned by many who suggest that he played a part during the Armenian Genocide. It is that perception that Mirak-Weissbach wants to clear.

The general, born in what is now Poland, led the Ottoman Fifth Army, a coalition of German, Turkish and Austro-Hungarian forces, is best known for his victory in Gallipoli.

“Of all the top military commanders, it was Liman von Sanders who played a major role in the reorganization of the Ottoman army and served as a military advisor to the Ottoman high command. As a result, Liman von Sanders was among the select number of German military officers whose name and legacy has been tarnished and marred in controversy for his direct or indirect involvement in various operations connected to the Armenian Genocide,” said Ara Ghazarians, the director fate Armenian Cultural Foundation in his introductory remarks.

Mirak-Weissbach, now based in Germany, is a former Fulbright scholar and a regular correspondent for the Armenian Mirror-Spectator. She researched Liman von Sanders for years, and in her new book, has written that research shows that in fact, the general was instrumental in saving many Armenians, Greeks and Jews in the Ottoman Empire.

In her talk, Mirak-Weissbach detailed her initial interest in Liman von Sanders through German-Canadian historian Fred Kaus who reached out to her about the general a decade ago. The municipal authorities at Darmstadt, where Liman von Sanders had been buried, had removed the honor grave marker from the general’s plot. “A historic commission had reviewed all such graves in the cemetery and stripped seven names from this honor, including Liman,” because their only achievement was through war, she said. Kaus had disagreed and petitioned for the honor to be restored because “he wasn’t just a military hero,” but had intervened during World War I to save thousands of Armenians and Greeks from the Genocide perpetrated by the Young Turk regime.

The commission refused and even suggested that the general for had played a role in executing the Armenian Genocide.

She noted, “This paradox disturbed me, not only for academic reasons but personal ones. Both my parents were orphans, survivors of the genocide who were rescued by kind-hearted Turks. If a German general had also saved Armenians, I wanted to know more.”

Thus, for eight years she dove into archives to learn more about him. “I found massive documentation which allowed me to put together the pieces of a complex puzzle and relay the incredible story of this man. I found he repeatedly and successfully opposed deportation orders coming from Enver Pasha,” she said. “As a result thousands of Greeks and Armenians escaped death.”

He also defended many Jews, as he himself had Jewish origins.

She stressed it is important to focus on people like Liman von Sanders, as the world is currently plagued with wars and injustices now, including the 2023 forced evacuation of Armenians from their ancient homeland in Karabakh (Artsakh).

“It is the innocent civilians who bear the greatest suffering,” she stressed.

Some suggest he could have stopped the Armenian Genocide, but Mirak-Weissbach disagreed. In 1915 he was leading the army in Gallipoli. He was in contact with Constantinople regularly, she said, “but it is highly unlikely he could do something about it in late April from Gallipoli. However, in February 1916, after the Gallipoli campaign, when he received a report from the governor of Adrianople (Edirne), had ordered the explain of all Armenians and Jews from the city,” with the aid of the German and Austrian ambassadors, “he succeeded in reversing the order,” she said.

She detailed several examples of Liman von Sanders coming to the aid of minorities in the Ottoman Empire. In one case, the government wanted to evacuate the Greek citizens “for their own safety. “A leading Greek representative of the community, as well as the Greek ambassador, reached out to the general, asking for his help.

The deportations had started when he arrived. He put a stop to them.

He took similar actions several times. Liman also set up an orphanage for Greek and Armenians, which he funded himself.

“In just about every case, Liman argued on the grounds of the so called military rationale to justify his resistance against deportation orders,” she said.

“In short,” she said, “there appeared to be a humanitarian impulse.”

Liman von Sanders was arrested in Malta in 1919 while he and his officers were leaving for Germany. “The entire affair was Kafkaesque and reads almost like a crime novel,” she said. No charges were ever filed, since neither the British nor the French governments could find anything on him.

He died in 1929.

She wondered why his name is still tainted. “Because they argue that the German commander could have at least prevented the genocide given that he had dictatorial powers,” she said. “The documents show he had no such dictatorial powers. It was the imperial government in Berlin, not the German military in Turkey, who determined imperial policy.”

And the one who devised the imperial policy, Chancellor Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg , who replied to a question about why Germany was not intervening in the Genocide: “Our only aim is to keep Turkey on our side until the end of the war no matter whether as a result Armenians perish or not.”

The blemish on his record, she said, was that though he himself had tried to help Armenians whenever possible, during his testimony at the trial of Soghomon Tehlirian in Berlin, “categorically denied any German participation in the atrocities. Why? Above all, Liman considered himself a man of honor.”

A reception followed the lecture.

Mirak-Weissbach’s book is on sale now at the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research, through the publisher and elsewhere.