by Artsvi Bakhchinyan

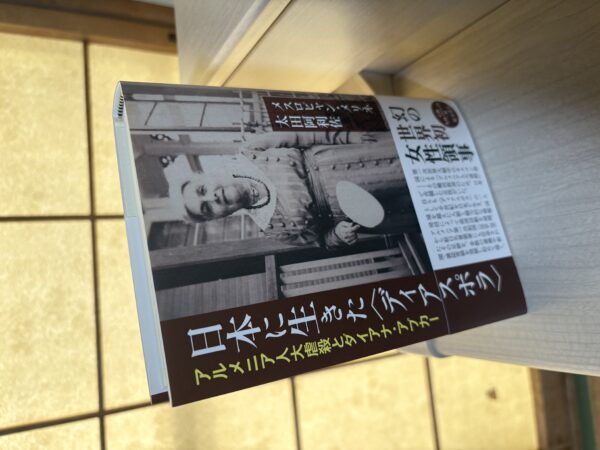

YEREVAN-KOBE, Japan — Meline Mesropyan (born in Yerevan) studied Japanese at the Yerevan Institute of Humanities before working at a travel agency for a few years. She has lived in Japan since 2011. In 2025, she co-authored the Japanese-language book The “Diaspora” that Lived in Japan: Diana Apcar and the Armenian Genocide, a study of Diana Apcar (1859–1937), an Armenian-born businesswoman, writer, humanitarian, and Honorary Consul of Armenia in Japan.

Dear Meline, how did you end up in Japan?

I began studying Japanese at the Yerevan Institute of Humanities, and I quickly fell in love with the language. It was difficult, but fascinating — full of cultural layers. Like many students of Japanese, I started to dream of one day living in Japan. In 2010, I took the entrance examination and received a scholarship from Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to continue my studies at a Japanese university.

I moved to Japan in October 2011 as a researcher and settled in Sendai, home to Tohoku University. In 2013, I entered Tohoku University’s master’s program and then continued to doctoral studies, where I wrote my dissertation on Diana Apcar. Today, I teach courses such as “Global Europe,” “Japanese Culture and Society,” and English and Russian at universities in Kobe and Osaka. Last year, I also had the chance to teach Armenian for one year at Kobe City University of Foreign Studies. I had seven students, and their enthusiasm was truly moving. We even held an Armenian food gathering at the end of the year, cooking dishes like harisa and tolma together, and sharing gata for dessert. Unfortunately, the course could not continue due to reductions in teaching hours, but the students kept writing to me with Armenian grammar questions for nearly a year afterward. I hope I can revive such classes again in the future.

I congratulate you on the publication of your Japanese-language work devoted to one of the most fascinating women in our history, Diana Apcar. Since 2004, I have written about her on a regular basis, exploring the Armenian press of the time and studying archival materials; however, there was a need not to repeat what had already been said many times, but rather to incorporate information from Japanese sources in particular. This could only be done by a researcher with knowledge of Japanese, which you have accomplished over the past 13 years. What path did your work take, and where has it arrived?

Thank you! When I arrived in Japan I planned to specialize in Japanese psycholinguistics. That changed after a conversation with a friend who was then working as a diplomat in Tokyo. He suggested that, since I already spoke Japanese, I might consider a topic that connected Armenia and Japan. At that moment, I remembered a photograph I had once seen at the Armenian Embassy in Tokyo, an image of Diana, whose name I learned at school, but realized how little I actually knew about her life. That moment marked the real beginning of my research journey.

That very evening, back in my hotel room, I began searching for her name. The first writing I encountered was by the Japanese researcher Hideharu Nakajima, who had discovered Diana Apcar’s grave in Yokohama. Almost simultaneously, my family in Yerevan informed me that a booklet on Apcar, containing your article, Artsvi, had just been published in New Julfa. At such an early stage, this was crucial, not only as a source, but as confirmation that her life could and should be studied seriously. Your work became one of the foundations on which I began to build my own research.

As I delved deeper, I was struck by how limited and fragmented the existing scholarship was, especially in Japanese and international literature. Very little attention had been paid to her concrete actions, her interactions with Japanese authorities, or the practical mechanisms behind her humanitarian work. From the outset, my aim was not to portray her as a heroic figure, but to understand her as a historical actor operating within specific political, institutional, and social constraints.

My research took on a strongly archival and transnational character. Alongside Japanese official records, newspapers, and administrative documents, I worked with correspondence preserved in European and American archives. Although Apcar lived in Japan, her intellectual and humanitarian activities were embedded in a wide international network, and many of her letters survive outside Japan, in the personal papers of prominent figures.

This work was complicated by the loss of many of her personal papers, destroyed in the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 and later during the Second World War. To reconstruct her life, I relied on materials in multiple languages such as Japanese, English, Armenian, Russian and French, carefully cross-referencing sources and piecing together fragmented evidence across archives in cities such as Sendai, Yokohama, Tokyo, Kobe, Hiroshima, Tsuruga, etc.

Over time, this approach led to a number of important discoveries and, above all, to a solid documentary framework that allows us to see Diana Apcar as a historically situated individual responding to the political and humanitarian crises of her time.

After moving from Sendai to Kobe in 2021, my research gained an additional layer of immediacy. Living in a city where Apcar had spent part of her life made the past feel more tangible, especially when walking through areas where her family’s hotel and business office had once stood. This research also led naturally to my current work on Armenian refugees who passed through Japan between 1915 and 1930. While this represents a new phase of research, it grew directly out of the questions first raised through my study of Diana Apcar. I am convinced that many relevant documents remain undiscovered, and I continue to search for them, committed to bringing these overlooked histories into the light.

Your co-author is Arisa Ohta.

The book was published in collaboration with journalist Arisa Ohta, whom I was introduced to by the publisher Fujiwara Shoten at an early stage of the project. The publisher proposed a co-authored volume to present Diana Apcar’s life in clear, accessible Japanese while firmly situating it within Japan’s historical and social context. This approach essential for conveying the significance of her work in Japan. Arisa Ohta’s contribution went far beyond linguistic refinement. Throughout the writing process, she consistently challenged my interpretations with sharp, thoughtful questions, ensuring historical accuracy, balance, and clarity for Japanese readers. Through this dialogue between academic research and journalistic practice, the book gained an additional layer of clarity and accessibility. During our collaboration, Arisa also conducted her own investigations, which led to several important findings, including the identification of the previously unknown grave of one of Dianas children in Yokohama and the discovery of a document clarifying Diana’s close relationship with a foreign resident woman involved in fundraising for Armenian refugees. These findings helped complete aspects of the historical narrative that had long remained fragmentary.

This book was shaped through the involvement of many individuals who supported the research at different stages. I already mentioned late Hideharu Nakajima, who shared his materials and insights and accompanied me to Yokohama to visit the grave he had long cared for.

Shinji Shigematsu’s research on Apcar & Co. as well as the hotel business clarified the Armenian commercial presence in Yokohama. After I moved to Kobe in 2021, Professor Shigematsu and his research colleague Ryohei Taniguchi jointly encouraged me to visit the Kobe Foreign Cemetery. During that visit, I identified the grave of Martin Khachatoor Galstaun, the father-in-law of Diana’s daughter Rose. The same visit also revealed that Diana’s husband had two separate graves.

Grant Pogosyan, the first Ambassador of Armenia to Japan, supported my research from its early stages and continued to assist after the completion of my PhD, including in the search for a publisher. Former Ambassador Areg Hovhannisian and the current Ambassador Monica Simonyan sustained this initiative through the Embassy of Armenia in Japan.

Diana’s great-granddaughter, Mimi Malayan, has been connected to my research for more than a decade. Her openness and strong sense of responsibility toward her great-grandmother’s legacy made long-term work on this subject possible, and our collaboration continues today through ongoing projects related to Diana Apcar.

I would also like to remember Lucille Apcar, Diana’s granddaughter, who passed away in 2021. Her memoir, written from childhood memory, was an invaluable source for my research and had already played an important role in earlier Armenian scholarship. Our correspondence, which continued until the final months of her life, allowed me to trace the descendants of Diana’s sister in England and reconstruct the wider family network. Lucille was remarkably honest and sometimes disarmingly direct. I still remember her once writing to me, after many questions, “Meline, do you think I am an encyclopedia?” This remark remains a reminder of both the limits of memory and the responsibility of the researcher.

Many descendants of Armenian survivors who passed through Diana Apcar’s care shared family archives, letters, photographs, and memories that brought her humanitarian work vividly to life.

Additional support came from Liz Chater, who guided me toward crucial sources; from Fujiwara Shoten and its director Yoshio Fujiwara, whose interest in Armenia and Diana made the publication possible; and from our editor Taku Kariya, whose meticulous attention to detail shaped the final manuscript. The assistance of the library staff at Tohoku University and of many colleagues in Japan, Armenia, and abroad also played an important role throughout this research.

In 2017, at my request, the Daisaku Watanabe, who knows Armenian, wrote an Armenian-language article “Japanese Materials on Diana Apcar,” where he mentioned: “because of the scarcity of materials about Apcar and the dispersal of her descendants throughout the world, many questions still remain in the study of her life and work and await clarification. We hope that this gap will be filled through cooperation between scholars of Armenia and Japan.” Could you indicate what you managed to uncover?

Daisaku’s observation was absolutely right. When I began this research, it was already clear that many questions about Diana remained unanswered, not due to a lack of interest, but because the sources were scattered across countries, languages and archives. What my research gradually demonstrated was how much becomes visible once Armenian materials are read alongside Japanese and international sources.

One of my main contributions was reconstructing Diana’s life as a whole rather than in fragments. This included tracing her family background, childhood environment, education, and early marriage, which helped explain how her worldview was formed long before her arrival in Japan. I was also able to clarify why the Apcar family came to Japan not as newlywed travelers, but as businesspeople.

Another major discovery concerned her writings. When I began my research, fewer than twenty articles by Diana were known. Through long-term archival work, I identified more than 180 articles published between roughly 1904 and 1936 in Japanese and international newspapers and journals. This made it possible to follow the development of her political and humanitarian ideas over more than three decades and to see how consistently she engaged with international affairs and the Armenian cause.

Equally important were her private letters with prominent figures. These correspondences revealed a more personal side of Diana Apcar: her doubts, frustrations, long-term strategies, and inner reflections, which never appeared in her published writings.

From an institutional perspective, a key finding was the discovery, during my master’s research in 2013, of Japanese diplomatic documents related to her appointment as Honorary Consul of the First Republic of Armenia. These materials clarified how her appointment was understood within Japanese official circles and helped correct exaggerated or inaccurate claims that continue to circulate.

In addition, correspondence with the Japanese Home Ministry and Foreign Ministry shed light on how Armenian refugee requests were handled in practice. Read together with documents from the American Red Cross in Vladivostok, these sources reveal the concrete mechanics of humanitarian even within a strict immigration regime.

My research also showed that Diana’s relationship with Japan evolved over time. Across three decades, her writings and correspondence reflect a gradual shift from cautious distance to a more complex mixture of attachment, criticism, and emotions. Recognizing it is important for understanding her as a long-term Japanese resident, not only as a humanitarian figure.

Finally, I want to emphasize that this research builds directly on earlier Armenian scholarship, especially your own work, Artsvi. My contribution was not to replace that foundation, but to extend it by placing Armenian sources within a broader Japanese and international documentary framework. Through cross-reading sources across languages and archives, a more continuous, nuanced, and historically grounded picture of Diana Apcar’s life has begun to emerge, and I believe there is still more to discover.

Over the past decade, Diana Apcar has seemingly become fashionable. In particular, the claim that she was the world’s first female ambassador is frequently exploited. However, it is known that already in the 17th century there were women ambassadors, such as the Dutchwoman Bartholda van Swieten and the Swede Catharina Stopia. Nevertheless, we can state with pride that Diana Apcar was the first Armenian woman to engage in diplomatic activity.

Diana is often described as “the world’s first woman diplomat” or “the first woman ambassador,” claims that do not withstand academic scrutiny. Diana was appointed honorary consul by the First Republic of Armenia, a newly independent and politically fragile state. Under the international law of the period, honorary consuls, especially those residing in the host country and not salaried by the appointing government, were not regarded as diplomats, even when they performed diplomatic functions. Her appointment was not formally recognized by the Japanese government, and therefore did not confer official status. At the same time, it is undeniable that Diana carried out diplomatic work in practice. From around 1910 through the late 1920s, she negotiated with governments, corresponded with international organizations, advocated for refugees, and acted as a representative voice for Armenians, often without the backing of a sovereign state. This is why her great-granddaughter, Mimi Malayan, later chose the title for her documentary The Stateless Diplomat: not to assert formal rank, but to describe a woman who performed diplomatic work without state protection, both before and after her official appointment.

What can be stated with confidence, and with pride, is that Diana Apcar was the first Armenian woman to engage in sustained diplomatic activity. Her work represents an early and remarkable example of Armenian participation in international humanitarian and diplomatic networks. Understanding her within the legal, political, and historical conditions of her time does not diminish her importance. On the contrary, it allows us to appreciate the originality and courage of her actions without relying on mythologized titles.

Let us examine another contentious issue. Archival documents attest that on July 22, 1920, Diana Apcar was appointed diplomatic representative of the First Republic of Armenia, with the rank of honorary consul. Because of historical circumstances, this appointment remained unilateral: by the end of 1920 the Republic of Armenia had ceased to exist, and Apcar was never officially recognized by the government of Japan as Armenia’s consul. Nevertheless, I believe that this episode also in no way diminishes the fact of Diana Apcar’s appointment as honorary consul of the Republic of Armenia.

I fully agree that the lack of formal recognition by the Japanese government does not diminish the historical significance of Diana Apcar’s appointment as Honorary Consul. On the contrary, the appointment itself was remarkable, as it formally acknowledged more than a decade of sustained humanitarian, political, and advocacy work she had already carried out on behalf of Armenians.

At the same time, this episode requires careful interpretation. Diplomatic and consular appointments in the early twentieth century operated within a complex legal and political framework, particularly for newly established states such as the First Republic of Armenia. Apcar’s appointment was a unilateral act by a fragile and internationally vulnerable republic whose existence was under constant threat. By the end of 1920, the Armenian Republic had ceased to exist, making recognition by host governments increasingly unlikely.

Few people know that Diana Apcar also wrote both prose and verse. I read her novel Susan, which has an autobiographical character and is one of the very few works of fiction devoted to the Indo-Armenian community. Did you also address her literary legacy?

Yes, I addressed Diana’s literary works alongside her political and humanitarian writings. In addition to her essays and advocacy, she also produced works of fiction, both prose and poetry, which form an important but often overlooked part of her intellectual legacy. She wrote two prose fictional works. Literary in form, they draw closely on the social worlds Apcar knew, reflecting the lived realities of Armenian diaspora communities and colonial-era societies. While not autobiographical in a strict sense, they are deeply shaped by her experiences and observations.

Susan, which you mention, stands out for its strong autobiographical tone and is among the few fictional works portraying the Indian Armenian experience from within. Susan had many common characteristics with Diana herself. However, I should note that Diana’s relationship with her mother was likely very good, unlike Susan’s.

I also examined Home Stories of the War, a series that occupies a space between literature, testimony and moral reflection. These narrative sketches convey the human cost of war through everyday lives, particularly those of women and children. In both cases, the stories suggest a close engagement with the realities of their time and place.

This autumn it will be 15 years since you moved to Japan, where you have started a family. Have you managed to pass on lessons of Armenian identity to your child?

Yes, time flies! Passing on Armenian identity to my son is something I try to do within the realities of school life and a multilingual environment. My husband, Jeremy September, is from South Africa. He is an economist and teaches at Hyogo University. He speaks English with him, Japanese dominates his daily life, and from birth I made a conscious decision to speak only Armenian with him. His Armenian naturally lags behind his Japanese and English, especially given the limited Armenian children’s content, but reading and storytelling remain central for us. He loves the story of Anahit and Hayk Nahapet, perhaps not by chance, as his own name is Hayk. I do not expect Armenian identity to come effortlessly; what matters is planting the seed, so that one day he knows where he comes from and feels free to return to it in his own way.