As Armenians celebrated Vardavar in late July at the Temple of Garni, the origins of this magnificent, 1st century AD, Greco-Roman structure are still contentious, to say the least. With numerous competing theories about its genesis, use and purpose, one possibility is that the temple was built as a monument to the “bromance” between Roman Emperor Nero and Armenian King Tiridates I.

In the first century, AD, Armenia found itself as a buffer state between Roman and Parthian Empires. Parthian King Vologaesus I replaced the previous Armenian king with his own brother, Tiridates, to establish a new Armenian wing to the Arsacid house. This Parthian election meddling didn’t sit well with the Roman Empire. As a compromise in an ongoing conflict, the two superpowers agreed that in the future, the King of Armenia was to be a Parthian prince, but the appointment required confirmation from Rome. To symbolize this submission, Tiridates I was summoned to Rome to gain the emperor’s approval. The rules of engagement were undefined.

At the peak of his manhood, Tiridates I was a gorgeous warrior with a glorious beard. Cassius Dio, a Roman historian, described the Mediterranean-looking king as “…in the prime of his life, a notable figure by reason of his youth, beauty, family, and intelligence” and noted that Tiridates “resembled the early Romans in that, besides coming of a brilliant family possessing great strength of body…” Accompanied by his Queen and his sons, Tiridates I began the 9-month treacherous journey to Rome in 65 AD. His entourage included an impressive court; many lords, sages, 3,000 Parthian horsemen, and a large group of Romans. Think 300, the movie, times ten. Opulent gifts and rarities were in tow as political dowry to the “eccentric” emperor.

Nero, on the other hand, was a brutal figure with a stern face. Adopted by his great-uncle Emperor Claudius, Nero become his heir and successor. An emperor at 16, he married his step-sister Claudia Octavia in 53 AD. While in a barren marriage, Nero had an affair with his friend’s wife Poppaea Sabina. Finding out that Poppaea was pregnant with his child, Nero quickly divorced Claudia, and married Popaea in 62 AD. Nero’s first and second wives, his mother and siblings were all murdered in questionable circumstances, likely in his command, in less than a decade. Consequently, he married his third wife, Statilia Messalina, in 66 AD. Then Nero met Tiridates.

Read also

Tiridates I’s caravan arrived in 66 AD. After meeting the Armenian king privately in Naples, Nero’s playground where he hosted hedonistic jamborees, the emperor invited Tiridates I to Rome. The city was bustling with grandiose reception ceremonies. The Eternal City was living its best life. For the public portion of ceremonies, complete with gladiator fights and animal cruelty, Nero came to the Forum clad in triumphant garments, surrounded by dignitaries, allies and swordmen. The climax of the coronation, prearranged in private negotiations, involved Nero sitting on the imperial throne several feet above everyone else, while Tiridates I approached through a corridor of heavily-armed guards. Although he kept his sword on, Roman historian Suetonius describes how Tiridates approached the emperor at the level of his knees (subeuntem…ad genua) and knelt down, with his hands to his chest, he addressed the emperor once the thundering cheers died down.

“Master, I am the descendant of Arsaces, brother of the kings Vologaesus and Pacorus, and thy slave. And I have come to thee, my god, to worship thee as I do Mithras. The destiny thou spinnest for me shall be mine; for thou art my Fortune and my Fate,” recorded Cassius Dio. Nero reciprocated in kind, affirming his dominance by proclaiming, “I have [the] power to take away kingdoms and to bestow them.” Only then, formally, did Nero place the diadem upon Tiridates I’s head declaring him King of Armenia. The men took a liking to each other, and as it was customary at the time, engaged in slaying wild beasts while touring the Empire in chariots. Spending enough one on one time with the emperor to influence his concepts of divinity, Tiridates I “brought Nero to Jesus.” Infatuated by Armenian king’s wisdom and spirituality, Nero converted to Mithraism, a devotion to pre-Christian, pegan theological God of Sun, a religion practiced in Armenia at the time. As the bromance of the century ran its course, Nero reluctantly released Tiridates I with a generous parting gift; 200,000,000 sesterces, estimated to be upwards of two billion dollars (adjusted for inflation) to rebuild Artaxata, current day Artashat, Armenia.

Following Tiridates I’s departure, in 67 AD, Nero fell in love one last time, with a man—Sporus. Although homosexuality was not uncommon in the Roman Empire, the marriage of Nero and an18 year-old freed slave was unprecedented as it was made official in a wedding ceremony. Nero and Sporus appeared in public as spouses and accompanied each other on international delegations. A year into their marriage, the political upheavals in the Empire drove Nero to commit suicide. Sporus’s fate was not much rosier. He became a possession of four emperors that followed, and committed suicide in 69 AD at 20 years of age to save himself from further humiliation.

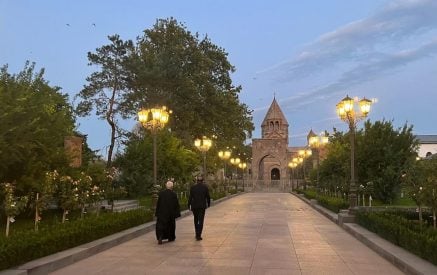

Nine years after Nero’s death, in 77 AD, Tiridates finally completed the Temple of Garni with the help of expert Roman craftsmen sent by Nero. This unmistakably Hellenistic Temple of devotion stands 2,500 miles from Rome and 1,500 miles from Athens. It is the only remaining pagan structure of its kind in the former Soviet Union territory. The symbol of a mysterious union between Nero’s and Tiridates I, Temple of Garni, is one of the most visited tourist attractions in Armenia today. There, every July 28th, followers of Tiridates’ faith celebrate the festival of Vardavar by drenching each other with water, a tradition that began in pagan times. So the next time you find yourself at the Temple of Garni, reimagine the circumstances in Ancient Rome that begot its construction— likely a love story between two powerful men.

Bibliography: Lerouge, Charlotte. L’image Des Parthes Dans Le Monde Gréco-Romain : Du Début Du Ier Siècle Av. J.-C. Jusqu’à La Fin Du Haut-Empire Romain. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2007. Rose, C. “The Parthians in Augustan Rome.” AJA 109, no. 1 (2005): 21–75. Schneider, R.M. “Die Fascination Des Fiends: Balder Der Prather Und des Orient in Rom.” In: Das Parterres Und Seine Zeugmas’, 95–127. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998.. “Friend and Foe: The Orient in Rome.” In: The Age of the Parthians, II:50–86. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007. Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002.

Armen ABELYAN