The Armenian Weekly. “Dear and blessed Armenians, villagers, when you return to the fatherland, as a gift, one by one, get your friend and relative a gun, get a gun and more guns. People, before all else, put the hope of your independence on yourself.”

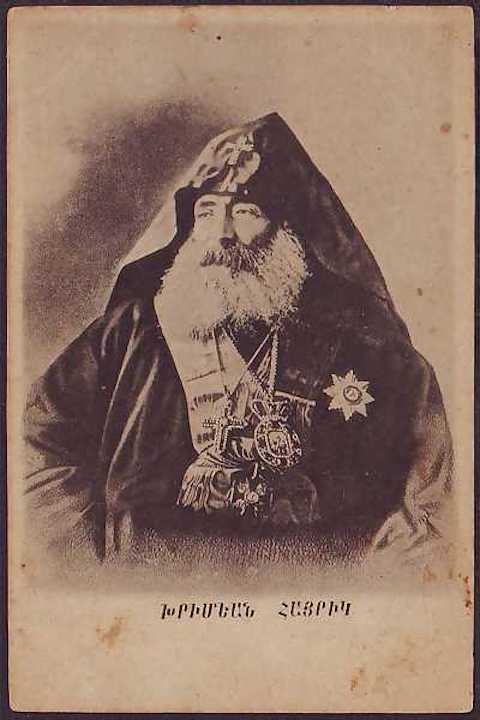

This excerpt is from the most famous sermon in modern Armenian history. Its message, that Armenians must cease their hopeful reliance on foreign powers, is taught in textbooks throughout the Diaspora. The man behind the speech, Mkrtich Khrimian “Hayrik,” occupies an outsized role in the Armenian national memory. He is the fiery cleric who beseeched Armenians to defend themselves and became known as the father of the revolutionary movement. A rare figure of history who is beloved by most everyone, Khrimian is considered an “honorary Dashnak,” a founding member of the Armenakan party. His name was often invoked within the pages of the official publication of the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia, all while simultaneously remaining a revered figure in the Armenian Church, respected for both his piety and devotion to his flock.

However, over the decades since his death, Khrimian’s legacy has been overtaken by the “Sermon on the Sword” mentioned above, which he first delivered in 1878 in the Armenian Cathedral in Kum Kapu. While the iron ladle metaphor he employed still resonates with contemporary audiences, Khrimian’s other myriad contributions to the development of the Armenian mind and the amelioration of the state of the villager have been left understudied.

Aside from his role as a pioneer in encouraging self-reliance, Khrimian also dedicated much of his life to educating the rural Armenian. Though the majority of Armenians lived in the vulnerable and vital eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire—the Armenian fatherland—most resources were poured into developing the Armenian community in Istanbul. Khrimian was among the first to shift the focus from Istanbul to the eastern provinces to not only speak to the villager, but also to give the villager a voice.

Khrimian published a combination of nine essays and books between 1855 and 1901. During that time, he also wrote articles for, while also acting as editor and publisher of, two periodicals, Artsvi Vaspurakan and Artsvik Tarono. Throughout these texts, certain themes arise which were vital for Khrimian including gender and the financial stability of the villager.

However, one of the themes which was most frequently discussed and important to Khrimian was education and the enlightenment of the Armenian peasant. This essay will serve as an analysis of one of his seminal texts, Papik ev Tornik, as well as the Artsvi Vaspurakan publication as a sampling of his intellectual and literary output regarding his efforts to educate the rural Armenian population.

Long before he exhorted the carrying of arms as a solution to the critical plight of the Armenians, Khrimian entreated the value of education as a salvaging force. Within the first page of the introduction to Papik ev Tornik, Khrimian posed the following question directly to his reader asking, “What is the reason why even with all the good you have, you are always left deprived?” To this he answered, “Read Papik ev Tornik and you will learn that the only cause is ignorance…not knowing how to read, write, count and economize.” Khrimian frequently wrote that ignorance and lack of education were the root causes behind hardship. He also championed the idea that all Armenians, including women, should be educated; the education of the individual would lead to a more prosperous Armenian society within the Ottoman Empire.

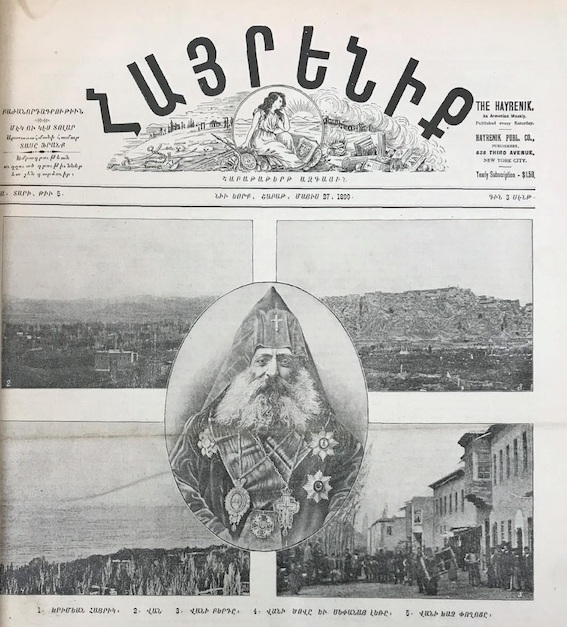

Less than a month after the publication of the Hairenik’s first issue, there arose a need to financially assist the Armenians of Van. The Hairenik published its first images toward that end. This is the front page of the May 27, 1899 issue featuring Khrimian Hayrik at the center.

Though Khrimian placed his emphasis on education, he did not advocate for formal education alone as the only avenue to escape ignorance. In the chapter of Papik ev Tornik titled, “Amelioration of the State of the Villager,” he extolled the intrinsic value of books, writing, “You know, grandson, every book is its own teacher for the reader. The authors have died, but the writing has remained alive. There are those kinds of books that are immortal, thousands of years can pass and they still speak to us.” This statement achieved two goals. Firstly, it worked to instill a respect within the Armenian peasant for reading; Khrimian’s statement posited the power of the book as a transmitter of knowledge which needed no mediator. Secondly, and more importantly, the statement gave the average rural Armenian a degree of agency over his education.

In the third issue of Artsvi Vaspurakan, printed in 1861, Khrimian argued for the need for Armenian public schools and challenged the popular belief that only the clergy needed to be educated, writing, “Who has decided for the Armenian people that they must suffer eternally in this dungeon of ignorance or hell? Is Christ’s able hand going to come back down to earth again and free them, perhaps?” The author answered his own cheeky rhetorical question by saying that the only solutions that would help the Armenians were public school and education. Here as well there was a connection between education and agency. Khrimian, despite being a cleric and soon-to-be Patriarch and eventually Catholicos, told his readers not to wait on God’s grace, but to free themselves from their dire situation through their education.

Aside from directly discussing the role and status of education in the development of the individual, many articles were themselves dedicated to educating the rural Armenian. One such example was the “Tesarank Hayreni Ashkharhats” series in Artsvi Vaspurakan which informed readers about different regions of the Armenian fatherland. This section provided the reader with important details oftentimes regarding either their surrounding regions or their own hometowns.

For instance, in the first publication of 1858, Khrimian printed a piece on the monastery of Varag in Vaspurakan. The article provided extensive information on the region including weather, its surroundings, topography, physical features, indigenous crops and the monastery itself.

Examples like this abound throughout Artsvi Vaspurakan’s publication. In the third issue of 1859, an article was dedicated to the scientific explanation of earthquakes. The catalyst of this article emerged after an earthquake occurred in Erzurum which led to the spread of “terrible myths” about what caused it, the worst result of which was that the youth believed in these myths and showed no further interest in learning the correct cause and thus remained ignorant. This compelled the author to write an article explaining the scientific process behind earthquakes in order to dispel superstition.

Lastly, Artsvi took up the mantle of educating its readership by engaging in pertinent contemporary discussions. One such example was a provocative and satirical piece on the debate of whether to use grabar (Classical Armenian) or the vernacular. The article, written by Khrimian’s student Garegin Sruandzeants, was styled as a tongue-in-cheek conversation between grabar and the vernacular themselves, each extolling its own virtue while insulting the other. After having already sparred for a number of pages, grabar responds to vernacular’s claim that its time has passed. Grabar exclaims, “հնացայ ու անցա՞յ, հըյ․․․անշնորհք, գիտե՞ս ով եմ ես․․․Քրիստոսի սուրբ Աւետարան ու շարական ինձմով են ծնած ու կնքուած,” to which the vernacular retorts simply: “Աստուած հոգիդ լուսաւորէ․” It was a rare example of satire and humor in the publication, but more importantly, it invited the reader to participate in the national discourse and a pivotal development which was occurring in their time.

Khrimian’s image and legacy performed a specific role in the decades following his death, usually as the convenient and tidy embodiment of the nationalist and revolutionary movement which was brewing in the second half of the 19th century. Khrimian was undoubtedly a pivotal figure in the Armenian nationalist narrative and the revolutionary movement that came to fruition then.

Yet, confining Mkrtich Khrimian’s historical legacy to a single speech precludes an objective study of the vast impact Khrimian had on the development of the Armenians of the eastern provinces, the social dynamic of the Armenian millet and the perceived role of millet representation within the Ottoman Empire. The current limited understanding of Khrimian can only be expanded through a holistic analysis of his work and publications. This approach removes Khrimian as solely a character in Armenian history and portrays him as a transmitter of social, political and intellectual change, as much informed by the many changes surrounding him as he, in turn, shaped them.

Main caption Khrimian: Hayrik sometime before 1903 (Photo: S. Soghomonyan