The Armenian Weekly. On the first day of kindergarten in Boulder, Colorado, we gathered in a circle, and the teacher asked us to stand up, introduce ourselves and tell everyone where we were from. I stood up, and without an instant’s pause, declared that my name was Levon and I was from Armenia. What my teacher and classmates didn’t know was that it would be another two years before I would set foot in Armenia for the first time.

Since then, I’ve moved around a lot. Today, I live in Boston, Massachusetts, which I now consider my hometown. Boston is home to one of the largest communities of the Armenian Diaspora, which has given me the opportunity to actively engage with my heritage. I’ve had fun at kebab nights and kefs. I’ve attended informative youth conferences and seminars, and I’ve networked at galas and fundraisers.

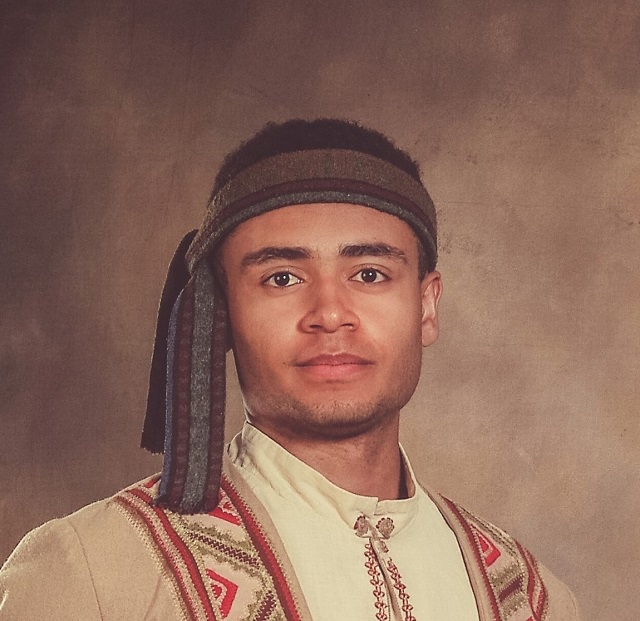

But one of the ways in which I’ve felt most connected to my Armenian roots has been through dance. In 2016 I joined the Sayat Nova Dance Company of Boston. Since I had gone to a boarding school in New Hampshire, I didn’t know anyone in the group or in the Boston area for that matter, so I was quite nervous to attend my first rehearsal. To break the ice, I baked chocolate chip cookies and shared them after practice as a way to learn everyone’s names. Turns out, I didn’t need the cookies. I was met with an incredibly warm welcome and felt the love and familial bond within the group right away.

After several months, I participated in my first major performance, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. It was an amazing and special opportunity for all of us, not only because we were showcasing the talents of our group, but because we were representing the culture and history of Armenia to tens of millions of people, as part of one of the most iconic and traditional American events. Since then, I’ve participated in a number of shows, and each time, as the audience fills the seats, I still feel that nervous energy while changing into my տարազ (costume), going over the footwork in my head, discussing any last minute changes with my fellow dancers backstage, and reminding myself to smile on stage.

Read also

But the minute the lights are dimmed, as we take our positions on the side of the stage and a hush falls over the audience with the rising curtain, I don’t have to remember to smile. All my nervousness sublimates, because when I take that stage and dance our ancient dances with a group that’s become like family, I recognize that I’m doing my part to keep our culture alive. This is the least I can do to honor my Yeranos medz papik and Yaghout medz tatik who survived the horror of Genocide and gave me a chance to live and to be Armenian. I get to honor my family that was murdered by the Ottomans, by doing the things they never had a chance to do –– by being here, by speaking our language, by eating our food, by singing our songs, by wearing our costumes, and by dancing our dances. This is the responsibility I have as an Armenian –– a responsibility I honor with solemn pride.

I’m not sure when, but I was given the nickname “Black Kochari” by some friends in the group. Kochari is a war dance—an expression of indomitable strength, courage and resilience. In kochari, we form an impenetrable line and shake the earth with the force of our feet to intimidate our enemies before going to battle. It was one of the first dances I saw and one that I always wanted to learn.

Being “Black Kochari” represents more than just having dark skin and dancing kochari. It represents the two embattled peoples of which I am a part.

As an Armenian, I know how deeply the effects of the Genocide have been etched into the Armenian psyche. We lost our families, our communities, our properties, our businesses and our right to live in our historic homeland. The damage of the Genocide is palpable, and we feel the consequences to this day, socially, economically and politically. We suffered then, and we continue to suffer now as Turkey continues a relentless worldwide campaign to erase the facts and the memory of the Genocide.

As recently as June 11th, a pro-Erdogan protest occurred in Lebanon, where Turks proudly yelled “F*ck Armenians.” Earlier this year, an Azerbaijani singer attempted to bar an Armenian singer from performing in the Dresden Opera Ball. Last year, a Turkish politician suggested naming children after the perpetrators of the Armenian Genocide.

In the US, Cenk Uygur—host of “The Young Turks”—has “recognized” the Armenian Genocide, but the program continues to bear the name of the political group that masterminded the Genocide. Last year, CBS’ “Seal Team” claimed that Armenia violated the ceasefire in Artsakh and that Azerbaijan is the only ally in the region, maliciously misinforming viewers who otherwise have no knowledge of the situation. During Turkish President Erdogan’s visit to the US, peacefully protesting American citizens (ethnic Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians) were attacked by Erdogan’s foreign agent bodyguards and his supporters outside the Turkish ambassador’s residence in Washington, DC.

These are some of the reasons why we protest every April 24th, why we take to the streets and demand reparations, why we continue to mourn the millions we lost. I’m told, “surely the sins of the father aren’t those of the son,” but when the son actively condones, encourages and continues the actions of his father, they become his sins as well.

As an Armenian, this is why I protest.

As a black American, I know how deeply the effects of slavery and segregation have been etched into the African-American psyche. Black Africans were brought to America as property, and in contrast to slavery in much of the rest of the world, not only were they slaves but so were their unborn children, grandchildren, and all future generations. My grandmother’s great-grandparents were slaves, nominally freed just 50 years before the Genocide. Despite being “freed” in 1865, black people in this country were not considered citizens until the passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868. And while laws may have finally granted them their humanity and person-hood, white society’s perception of them as subhuman had not changed. Black men and women had gained freedom, but despite years of labor had neither the inherited nor earned financial means or material possessions to survive.

Contemporary Americans often cite “40 acres and a mule”—the post-Civil War Order by Union General Sherman to redistribute Confederate land to former slaves—as an example of reparations after slavery and opportunity for black Americans to improve their lives. The sobering reality was that this decree, made in January of 1865, was overturned by President Andrew Johnson later in the same year, and the lands were returned to the original owners.

Sharecropping was the system that replaced slavery. It wasn’t a new system, as it had been used before the Civil War and all over the world, and sharecroppers were both black and white. Ideally, sharecroppers would live on a section of the plantation and pay part of their harvest to the plantation owner as rent. The intended benefits of this system were that sharecroppers could choose when to work, how long to work, what crops to plant, and eventually, they’d have earned enough money to buy their own land.

But again, like “40 acres and a mule,” reality didn’t meet expectations. The plantation owners established “Plantation Stores” and required that all sharecroppers use them for farming equipment and personal shopping. The prices in these stores were inflated to such a degree that sharecroppers had to buy on credit, with interest rates as high as 15 percent per month. After paying off their debts, sharecroppers often had no disposable income left, and if the harvest was poor they’d remain in debt till the next season, inordinately magnifying their debts. As those debts increased, sharecroppers would have to prioritize planting cash-crops rather than food for consumption. Because of how time-sensitive the planting and harvesting of those crops were, in the rare places where schools were available to black children, sharecroppers’ children would be taken out of school to work on the farms, ensuring the generational propagation of illiteracy and poverty, thereby making it impossible for black Americans to rise within society. This system of sharecropping is described as “wage slavery” since sharecroppers could never truly become “free.” It extended into the 1940s and in some places even the early 1950s.

Simultaneously, state and local laws, The Black Codes and later Jim Crow laws, enforced this disenfranchisement. In 1865, the Black Codes, a strict set of laws which dictated where and how black Americans could work and how much they could be compensated, were introduced. While these codes did bring some benefits, such as the right to buy property, to marry (but only other black people), to make contracts and to testify in court (but only against other black people), their primary purpose was to restrict black Americans. Specifically, these codes enforced:

- Limits on the type of property black people could own.

- Requirements to sign yearly labor contracts.

- Penalties for breaking labor contracts such as arrest, beatings and forced labor.

- “Apprenticeship” laws, which forced black minors, who were orphans or whose parents were deemed unable to support them by a judge, a judge who in the South was likely a former Confederate and landowner, into unpaid labor on white-owned land.

- Criminalization of various trivial behaviors, such as obscene language ([Callie Marie Rennison, Mary Dodge], Introduction to Criminal Justice: Systems, Diversity, and Change)

- Vagrancy laws, which paved a pathway for black men to be arrested for any minor offenses or whenever they were not employed in a place or manner approved by white authorities, then be leased by the prison system to work without compensation in white-owned businesses or lands.

The most important issue was that while they were nominally American citizens, black Americans had no representation in drafting or ratifying these laws. What happened to the principles that formed the foundation of the United States? What happened to no taxation without representation?

The Jim Crow laws, which were created when black Americans moved into cities during the 1880s, dictated the following:

- Theaters, restaurants, buses, trains, water fountains, restrooms, building entrances, elevators, cemeteries, public pools, phone booths, hospitals, asylums, jails, residential homes, even amusement-park cashier windows had to be segregated.

- Black people were barred from entering public parks.

- Black people were forbidden from living in white neighborhoods, were forced into specific areas (the subsequent ghettos), and those neighborhoods were then redlined and denied resources and funding.

- In some states, separate textbooks were required in schools, and in Atlanta a different Bible was required to be used by black people in court.

- Interracial marriage was banned in most states (akin to Nazi Germany and South Africa during apartheid).

During the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, black schools were destroyed, southern black Americans were intimidated out of their homes and innocent black Americans were tortured and lynched. The terror group ultimately added a layer of extralegal hardship to the black American community.

Certainly, it wasn’t just black Americans who were struggling with poverty and illiteracy. There were Irish and other immigrants who were also caught in the trap of wage slavery. The difference is that segregation, Black Codes and Jim Crow laws were specifically designed to disenfranchise and eliminate the political and economic agency of black Americans.

Furthermore, there were no “scientific” theories and widely held beliefs that the Irish, Italians or any other white Americans were inherently and genetically inferior. In the 19th and 20th centuries, academics would conduct studies and present “evidence” to legitimize slavery, justify their biases and excuse the inhumane treatment of black Americans.

For example, Samuel George Morton, a prominent 19th century American physician and scientist, asserted that African Americans were intellectually inferior based on his evaluation of the shape and size of their skulls. His contemporary Louis Agassiz, one of the most influential American scientists of his time, claimed that blacks were a “degraded and degenerate race.” Both argued that blacks were a separate species and used this as a basis for their staunch support of anti-miscegenation. Georges Cuvier, a leading French naturalist, “proved” the inferiority of Africans by showing that there was “no exception to this cruel law which seems to have condemned to eternal inferiority the races with cramped and compressed skulls.”

In 1925, pseudo-studies conducted by the Army Central Staff College concluded that black Americans were “unmoral” and “very susceptible to the influence of crowd psychology.” They asserted that “in the process of evolution the American Negro has not progressed as far as the other subspecies of the human family,” and that “he has not developed leadership qualities. His mental inferiority and the inherent weakness of his character are factors that must be considered… his normal physical activity is generally small due to his laziness.” (Stanley Sandler, Segregated Skies, p. 9).

As an additional way to assert the inferiority of black Americans, academics turned to statistics, compiling datasets of crimes which attempted to “objectively” show that black Americans had a disproportionate criminal propensity. For example, in 1890 there were 55 convicts serving their sentences as unpaid laborers in the Pratt Mines of Birmingham, Alabama. Of the 55, 24 had been arrested for “obscene language,” 24 were arrested for “false pretense” (specifically, changing employers before the end of a farming season), and seven were arrested for vagrancy, the ambiguous catch-all in the Black Codes to arrest unemployed black Americans.

If it isn’t apparent how nefarious this system was, I will elucidate—as a black person at that time, by law and by your inherent lack of education (also created by law), you were barred from almost every job aside from manual labor. If you didn’t want to be a laborer or between contracts, you were considered a vagrant, arrested, and brought to court. You weren’t allowed to defend yourself in court, because you could not speak against a white prosecutor, and you would have no peers in the jury, because black people couldn’t sit on juries. You were then labeled a criminal and forced into unpaid labor on the farm of a white landowner for the financial benefit of the state.

So with these grossly inflated crime statistics, as well as the pseudo-scientific studies of skulls, there was significant collective “evidence” to influence the opinion of many white Americans, re-enforcing the pre-existing racism of the older generation and engendering bigotry in the younger generations. I’m not suggesting anyone was born racist. I’m suggesting that if you were an average person at the time, and if you didn’t look further into the sources of crime statistics or question the validity of academic studies, you’d be led to believe that black Americans were in fact vastly inferior and altogether a different subspecies of human, and given their apparent propensity for crime, were imminently dangerous. Numbers are numbers, right?

You, your children and your grandchildren would grow up loathing and fearing black Americans, and by virtue of segregation you would have little to no opportunity to become more informed through meaningful interactions and conversations with black Americans. As a police officer, you’d approach encounters with more hostility and suspicion because statistics would lead you to believe that black people are more likely to commit crimes. In court, the white jury would be more likely to convict a black American or sentence them more harshly, because a priori “statistics” suggested that the black defendant was likely to be a criminal.

Interestingly, immigrants also had a disproportionately high crime rate, and their crimes were not of the Black Codes variety. Academics of the time such as Frederick Hoffman would praise immigrants for their ability to “melt like sugar in a cup of tea when they came to the United States,” while condemning and criticizing black Americans for remaining “distinctly African in their physical and mental characteristics.” He and other contemporary social scientists wrote off the disproportionate crime rates of immigrants as a “passing consequence of adjusting to the industrial city,” suggesting that the issues were temporary and environmental for immigrants but inherent and genetic for black Americans.

Not only did this influence white Americans, it influenced black Americans as well. In the words of Carter Woodson, “If you make a man feel that he is inferior, you do not have to compel him to accept an inferior status, for he will seek it himself” (The Mis-education of the Negro). This was shown in a series of psychological experiments in the 1940s known as The Doll Tests, where “children were asked to identify both the race of the dolls and which color doll they prefer. A majority of the black children preferred the white doll and assigned positive characteristics to it,” starkly signaling “a feeling of inferiority among African-American children and damaged [sic] self-esteem.”

One might think, “Well, wasn’t that a long time ago?” The truth is, it wasn’t all that long ago. Again, my grandmother’s great-grandparents were slaves. Her grandparents and parents were sharecroppers, and she worked alongside them as a child. My dad’s birth certificate lists him as “colored,” and he had to attend a segregated school almost two decades after Brown v. Board of Education. Changes in the law don’t necessarily reflect changes in society—the last school district in the US was desegregated in 2016, 62 years after segregation was ruled unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court. In places where schools had been desegregated earlier, many white parents pulled their children from public schools and enrolled them in white-only private academies.

Those fraudulent studies weren’t relics of a distant past either. William Shockley, the 1956 winner of the Nobel Prize for the creation of the transistor, sought “to prove that black Americans were suffering from ‘dysgenesis,’ or ‘retrogressive evolution.’” As recently as 2007, American biologist James Watson, recipient of the 1962 Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery of the DNA double helix, claimed that black people are inherently less intelligent than white people. While the controversy following his remarks eventually led to his resignation, his rekindling of scientific racism made it possible for questions like “is there any evidence there are major differences in the intellectual potential of races?” to rise in the 21st century.

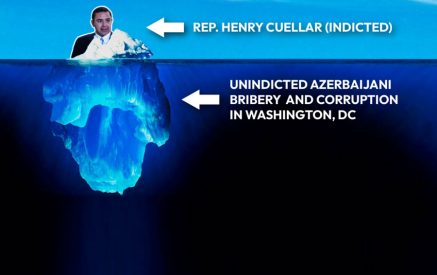

One might then ask, “what about crime statistics today, and ‘black-on-black’ crime?” Why do black Americans protest police violence when there is so much violence in their communities? Why do black Americans make up 12.7 percent of the population but 40 percent of the prison population? Mass incarceration of black people, and especially of black men, did not end with the Black Codes—black men continue to be disproportionately targeted for arrest and continue to receive harsher sentences for the exact same crimes (under the same criminal codes) compared to their white counterparts. “Statistics” like those in the following image, circulated not only by uninformed lay people, but by our President, perpetuate the myth of black Americans being disproportionately violent:

Then Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump retweeted this graphic of inaccurate homicide data on November 22, 2015

A look at the actual data from the FBI will immediately negate these:

- Blacks killed by whites were eight percent (not two percent as in the graphic).

- Of 1,103 people killed by police in 2015, 27 percent were black and 49 percent were white. In the general population, 12.7 percent of people are black and 73 percent of people are white.

- 2,664 black Americans died of homicide in 2015, and 297 black Americans were killed by police. Based on the available data, it isn’t clear if the 297 were included in the 2,664.

- If they were included, blacks killed by police were 11.1 percent (not one percent as in the graphic).

- If they weren’t included, then blacks killed by police were 10 percent (not one percent as in the graphic).

- 3,167 white Americans died of homicide in the same year, 540 were killed by police. Again, based on the available data, it isn’t clear if the 540 were included in the 3167.

- If they were included, whites killed by police were 17 percent (not three percent as in the graphic).

- If they weren’t included, then whites killed by police were 14.5 percent (not three percent as in the graphic).

- Whites killed by whites were 81 percent (not 16 percent as in the graphic).

- Whites killed by blacks were 15 percent (not 81 percent as in the graphic).

- Blacks killed by blacks were 89 percent (not 97 percent as in the graphic, and not too different than the “white on white” murder rate of 81 percent).

If you don’t believe me, look at the data sources and do the math yourself. Why are the number of whites killed by blacks so blatantly and hugely inflated? Because these statistics are borne of exactly the same bigotry as the fraudulent crime statistics of the past two centuries. They are intended to purposely misinform and implicitly bias, because rational people look at statistics and make decisions based on them. Did you know that while black Americans represent only 12 percent of the population of drug users (parallel to their representation in the general population), they make up 39 percent of those sentenced to federal prisons and 29 percent of those in state prisons for drug-related offenses? Among people arrested for cocaine-related offenses, 22 percent of those convicted for crack cocaine (cheaper and vastly more prevalent among black drug offenders) were sentenced to 20 years or more in prison, compared to 12 percent of those convicted for powder cocaine (more expensive and significantly more prevalent among white drug offenders).

One might then say, “there’s no more segregation today, no laws specifically oppressing them, so why are black people still complaining?”

Don’t black Americans have enough agency and opportunity to make a better life for themselves at this point? Compared to the past, yes, we have a much better chance, but this doesn’t mean the inherent problems of the system have disappeared. Just because I attend an Ivy League school, or Barack Obama became President, doesn’t mean the underlying issues have been solved. After all, Garo Paylan is an Armenian in the Turkish Parliament, and an Armenian Museum was opened in Turkey, but neither of these erase the consequences of the Genocide and the discrimination we continue to face as Armenians in Turkey and from the Turkish government and their agents abroad. Not only they themselves, but the children and the grandchildren raised by the people who cheered during “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, are living among us today. The values and beliefs held by people like George Wallace and by the children and grandchildren raised and taught by them, are undoubtedly guiding their personal and professional decisions and actions today.

Systemic racism is the accumulated disadvantage, the generational propagation of illiteracy and poverty, and the destruction of families and communities on the basis of race. If you force a race of people to live only in a specific area, then redline them and deny private and public investment to intentionally turn their neighborhoods into ghettos, then use property taxes as a way to fund public schools, it’s obvious that the schools in that area will be underfunded and underperforming. As a result, graduates of those schools will be less likely to go to college and obtain well-paying jobs. Their continued economic disadvantage will prevent them from leaving those ghettos and will perpetuate poor education and poverty through the next generation.

But there are poor white people too, who live in bad neighborhoods! Yes, there are many poor white people and a number of wealthy black people in our society today. Unfortunately, many white Americans, who don’t have generations of wealth or financial resources, have found themselves in a poverty trap as well. Regardless of their race, people who are economically disenfranchised face many of the same negative consequences as those enduring systemic racism, such as underfunded schools. However, you shouldn’t confuse economic disenfranchisement with racial disenfranchisement. They both exist, and they aren’t mutually exclusive. While poor white Americans contend with economic disadvantage alone, poor black Americans have to contend with both. When poor black and white Americans do manage to break out of the cycle and obtain an education and a job, a similarly educated black man working in a similar job earns 30 percent less than his white counterpart. The system was never designed to keep white Americans from advancing, it was specifically designed to repress and subjugate black Americans.

As an Armenian, why should I care?

As Armenians, if we can understand and appreciate how the Genocide not only devastated the families of our great-grandparents, but shaped our psyche and our future as a people, we should also understand and appreciate how slavery and segregation molded the current black American reality.

The Genocide is one of the primary reasons we live in Boston, Los Angeles and other diasporan communities. Slavery and segregation are the reason so many black people live in ghettos and poverty.

If you question why statues of Confederate “heroes” who actively fought to dissolve and destroy the United States in order to uphold slavery are being torn down, ask yourself as an American if we should erect glorified statues of other traitors, like Benedict Arnold, and ask yourself as an Armenian how you’d feel if statues of Talaat Pasha and Sultan Hamid were raised near those of Zoravar Andranik or Soghomon Tehlirian. Is that how history should be learned and memorialized?

Not all Turks were involved in perpetrating the Genocide, but the Turkish nation collectively benefited economically and geopolitically from the elimination of the Armenian population. Not all white Americans were involved in perpetrating slavery and segregation, but white Americans collectively benefited from the subjugation of black Americans.

Hatred and discrimination on the basis of race and ethnicity should be anathema to all Armenians—a people that saw and survived the horror of Genocide. Every time a black American is called a “monkey,” our Armenian consciousness should be jarred with memories of being called “it” (“dog/mutt” in Turkish). The cause of anti-racism should be the cause of every Armenian.

Levon Brunson

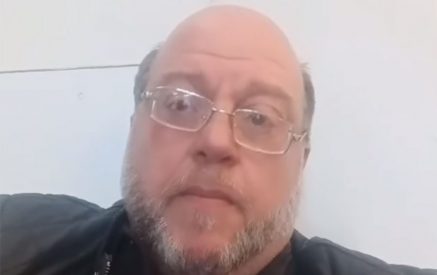

Main photo: Levon Brunson pictured in traditional daraz