The educator of thought must oppose any power

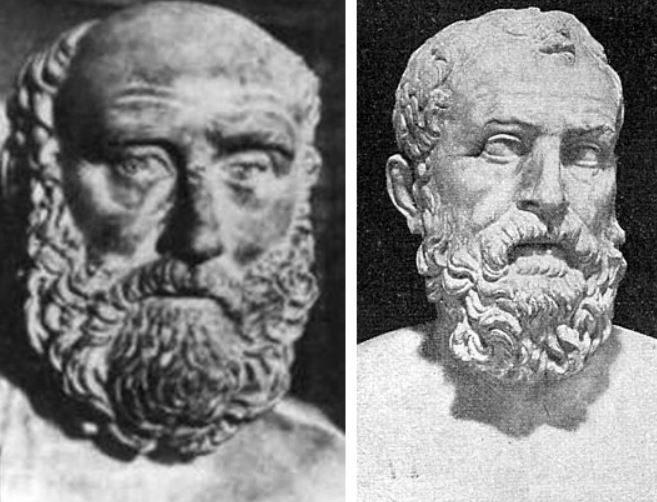

In ancient Greece in the 7th-6th centuries BC, there lived a figure, legislator, and poet named Solon. He was elected one of the governors of Athens, one of the archons, and authored laws that specifically abolished the debts that enslaved poor citizens. The poor, however, could not get rich and, naturally, remained dissatisfied. The aristocrats also suffered from these laws. In short, not being understood by all parties, Solon leaves the city for 10 years.

When he returned, he saw that one of his relatives, Pesistratus, had seized power through intrigue and had become a dictator. Solon comes out to the square and makes an accusatory speech. But the target of the accusation was not Pesistrat, but the citizens gathered in the square. “Since disaster struck you because of your shameful weakness, there is no point in blaming the gods for it,” says Solon. “And that’s why you got cruel slavery.” The dictator did not persecute Solon, as he was of considerable age, and one of the fathers of Athenian democracy devoted his last years to literature.

1992 marked the 2500th anniversary of democracy. The starting point was not the work of Solon, but the activities of Klisfen, who lived a few decades after him, who again carried out democratic reforms. But that is not the point. The cycle of repetitive plots is striking: the oscillation of democracy-dictatorship, the danger of democrats becoming dictators, people who sincerely fought against dictatorship, but then do not want to see their “defended” dictator. The identical nature of power (by and large, of any power). And most importantly, all this in the conditions of complete irresponsibility of the society. Citizens, from ancient Athens, do not realize, and if they do, they do not admit that they themselves have caused any disaster. Regardless of whether they have elected the government or have been installed as dictators, the citizens have what they deserve, no more, no less.

Read also

What can change the situation so that the citizens deserve something better? I think critical thinking. That phrase itself seems to me to be a tautology. Because the mind can not be uncritical. It is not critical, I think, the senseless repetition of propaganda slogans, real or imagined majority stereotypes. If it is an idea, then it must be opposed to what is natural, self-evident. But that speech cannot be “oppositional” in the sense in which we perceive the word in Armenia.

Here is what the 20th century French philosopher Roland Bart wrote: “Some of us, intellectuals, expect us to rebel against the government at every opportunity. However, it is not in that field that we wage our real battle, we wage it against all forms of power, and it is a difficult battle, because, being in the sphere of multiple social spaces, power is at the same time eternal in historical time; by pushing it out the door, it comes to us from the window. The government never dies, carry out a revolution, destroy the government, it will flourish again in a new situation.” Thus, the intellectual, the thinker must be opposed to any power. We are not talking about revolutionary or oppositional activities, because the opposition, the parties, the social movements are also the government in the sense described above. According to Bart, power lives in the hardened, mythological use of language. And in that sense (exclusively in that sense) the intellectual must oppose any, including the “power of the people.”

… In the same Ancient Athens there was such an order. From time to time the assembly of citizens could “ostracize” people, that is, expel them from the city for 10 years. The mechanism was as follows. Citizens wrote the name of the person who, according to the majority, should be expelled from the city on pottery pieces (shells). Theoretically, the name of an unloved neighbor could be written, but of course, political figures got the majority. And here is what they say about the general and politician Aristide. The latter was known for his modesty and decency. (In this he was, by the way, different from Themistocles, who, after manifesting himself heroically in the war, even, so to speak, rescuing Athens from the Persians, fell into the arms of corruption and luxury, and, according to Plutarch, annoyed the citizens by reminding them of his heroism). And before such a vote, a citizen approaches Aristide and, confessing that he is not literate, asks to write Aristide’s name on the “shell”. The commander asks, “What’s wrong with that man?” “To be honest,” the citizen replies, “I do not know him, I am not aware of his deeds, but in the market people often talk about his honesty, I do not like it.”

Aram Abrahamyan