From pagan prayers to Christian crosses, khachkars have witnessed the rise and fall of empires, and the ebb and flow of faith

Clad in the volcanic garb of tuff and basalt, Armenia’s pastoral architecture eschews the traditional cruciform design, echoing Mount Ararat. Within their walls, a tapestry of artistry unfolds, with painted frescoes and intricate stone carvings narrating Biblical tales. In a world where religion was often a source of conflict, Armenia took a refreshingly progressive approach, becoming the first nation to officially adopt Christianity in 301 AD. To spread the word, they didn’t rely on firebrand sermons or imposing cathedrals; instead, they turned to art, creating a unique form of religious expression – the khachkar. In Armenia, where time seems to pause, 50,000 stone tablets with their surfaces chiselled with a Celtic cross, inscriptions, interlocking laces, botanical motifs, and biblical figures whisper primordial tales, beneath celestial skies.

Hamlet Petrosyan, a senior Armenian historian, archaeologist, and anthropologist divulged, “The erection of khachkars began in the middle of the 9th century when the Bagratuni dynasty gained political independence. The cross was an open-air monument, and if the territory did not belong to you, the Arabs strictly forbade their use, and only with the wave of independence did the erection of cross-stones begin. Before the 9th century, there were crucifixes on various churches, on the apses of churches, on their windows, and on their pediments, and as a rule, early Christian monuments ended with winged crosses. But they were not khachkars. A khachkar is a slab that is specially designed only for cross-formation.”

Read also

Timeless sentinels inspired by the art of obelisk carving, these khachkar cross-stones, hailed as “Intangible Cultural Heritage” by Unesco in 2010, have etched their presence onto the Armenian landscape for centuries. khachkars, are carved on a variety of stones, ranging from the natural black stone to yellow-reddish tuff to the Basalt. Ruben Ghazaryan, a khachkar-maker, who honed his craft at the 13th-century Noravank monastery, works with the soft, felsite stone, a name synonymous with Momik, a famous medieval master architect. Whereas, Bogdan Hovhannisyan, another veteran khachkar-maker maintains the centuries-old tradition of khachkar carving at his workshop in Vanadzor, by carving on gypsum stone.

Babik Vardanyan, 42, a khachkar-maker whose ancestors were Kartash masters, shares, “My father started khachkar making in the 1970s. This was the Soviet period when Christianity was banned and most of the churches were closed. During this period, my father began to make khachkars, which were ordered mainly as tombstones. In the last 20 years, I have made over 200 khachkars, and each one of them is unique and has its distinct history. A khachkar is handmade. I use a cutter and a hammer. In ancient times, when there was no saw, people smoothed and moved the stones by hand, that’s why they were also called kartash (kar means stone in Armenian and tash/tashelis to smoothen, hack or prepare) masters. Now, of course, there are also electric tools that facilitate the processing of stone, but at the same time, human hands give soul to stone. On average, I work on each khachkar for 1-1.5 months, and making of more complex khachkars, takes three-six months.”

At the heart of every khachkar, a cross asserts its dominance, while beneath it, a rosette or solar disc gleams with celestial fervour. Intricate knots of stone intertwine like Celtic braids. The rest of the stone canvas is a chronicle of nature’s bounty, an idyllic tableau unfolding with a grapevine ballet, where slender tendrils pirouette amidst leaves, and pomegranates, with their ruby crowns, glisten with the promise of prosperity. The pièce de résistance, however, is the cornice, a sculpted crown that elevates the khachkar from a mere monument to a masterpiece. Upon this sacred stage, biblical scenes and revered saints come to life in stone, their timeless stories etched into the very fabric of the khachkar.

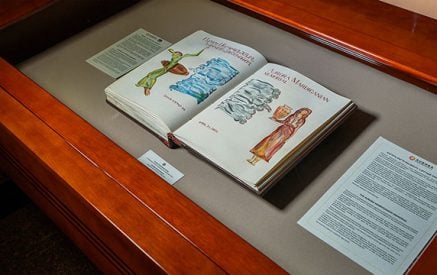

The priests equated the cross to a benevolent tree that offered refuge to the entire world. Inspired by this metaphor, artisans, with their nimble hands, transformed these divine symbols into enduring stone sculptures, while illuminators, with their artistic finesse, brought them to life on the pages of sacred texts. The deep-rooted notion of a world as a garden, long ingrained in the Armenian psyche, found a new home in the Christian cross, which initially confined to a rigid square, metamorphosed skyward, transforming into a tree of life.

Hamlet Petrosyan sheds light on the pagan influence of ancient khachkars and clarifies, “Christianity was a revolution. Pagan symbols were not used on cross-stones. There are several dragon stones (vishapakars), Artashesian stele-boundary stones, and Urartian inscribed stones, which have been turned or transferred into khachkars. In other words, people saw that it was a suitable monument, it was already elaborated, they took it and either scratched the signs or writings on it or re-carved it and turned it into a khachkar.” A Vishap, a peculiar carved idol often referred to as a dragon stone was displayed near water sources, considered sacred in pagan belief systems. Vishaps were even erected at sites of pagan worship. As Christianity gained traction and paganism waned, khachkar designs gradually shed their pagan influences, reflecting the changing religious landscape.

Sevak Arevshatyan, a 35-year-old historian from Yerevan, who has documented thousands of khachkars in a relentless pursuit of cultural preservation says, “Prior to the development of the khachkar in the mid-9th century, a variety of freestanding crosses were prevalent in Armenia. During the Middle Ages, when an individual performed a meritorious act for the community, such as establishing a village, constructing a church or bridge, or bridging a stream, they would commemorate and document that deed as a lasting tribute in the form of an inscription on the khachkar. In 1200, a khachkar was erected on the occasion of the victory of the joint Armenian-Georgian forces against the Seljuk-Turks, in Aragatsotn province.” He adds, “Today and as before, Armenians consider the khachkar exclusively a part of their own culture, the identification of the Armenian nation through the khachkar is so obvious that when you see a khachkar outside the borders of Armenia, you immediately notice that there is an Armenian here.”

The cross itself emerged as the valiant protagonist, seamlessly merging with the stone stele, and underwent a remarkable transformation by the seventh century. Its surroundings were gradually relegated to the background. As the khachkar emerged as a singular stone monument, it embraced a vector-like form, directing all attention towards the images etched on a single flat surface. This shift marked a significant departure from the stele’s more restrained aesthetic, allowing for a more intimate connection between the faithful and the divine. The intricate details, now visible at eye level, fostered a deeper engagement with the sacred imagery. The 12th to the 14th centuries marked the golden age of khachkar carving, a period when Armenian artisans reached the zenith of their artistic mastery. But, like a melody interrupted by a jarring note, the Mongol invasion of the late 14th century threw a wrench into this artistic crescendo. The art of khachkar carving took a nosedive, its once-brilliant flame flickering amidst the chaos. Yet, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, khachkar carving made a glorious comeback in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Across the annals of history, certain cross stones even ascended to the status of saints. These venerated stones were believed to avert cataclysms, mend ailments, and grant wishes. For warriors facing the perils of battle, St Gevorg khachkars whispered unparalleled bravery and invincibility. The ‘Cross of Fury,’ could appease divine wrath and ward off the dreaded quartet of drought, hail, earthquakes, and epidemics. And St Sargis stones tablets held the key to eternal bliss for star-crossed lovers. Among the countless works of exquisite craftsmanship that adorn khachkar carvings, three masterpieces rise above the rest. The first, the 1213 khachkar of Geghard, the second, the Holy Redeemer khachkar of Haghpat, carved in 1273 by the maestro Vahram, and finally, the khachkar in Goshavank, crafted in 1291 by the deft hands of Poghos.

“From the archaeological point of view, the biggest discovery was the excavation of Saint Stepanos Monastery in Artsakh, where we found 30 khachkars from under the ground, all of them mostly from the 12th-13th centuries. Their recording and preservation are dealt by the Department of Cultural Heritage Research. We also have a big project with Harutyun Khachatryan from Paris, where we are engaged in the digitization of these works, and have already finished Gegharkunik, Kotayk, and Aragatsotn provinces,” tells Hamlet Petrosyan to Forbes India.

Among this celestial chorus of stone stands the venerable granddaddy of them all, the oldest khachkar known to humankind, carved in 866, in Artsakh, Vaghuhas village, in the cemetery of the “Eghtsu Ktor” chapel. Hamlet Petrosyan, however, reveals, “There is a pedestal of the oldest dated khachkar, from the year 853, which is located in Saint Hakobavank monastery of Artsakh. Later, that pedestal was placed on the wall, however, unfortunately, the khachkar was not found.” He adds, “The khachkar dating back to 876 which is of Hortun village of Ararat province, now transferred to Vedi city, ranks second in its antiquity. And, the khachkar of Queen Katranide I, wife of King Ashot I Bagratuni, in Garni, carved in 879, is the 3rd-oldest khachkar of its kind.”

Today, the tradition of khachkar carving lives on, with dedicated artisans in a few Armenian cities continuing to breathe life into these timeless masterpieces. Narine Poladian, 28, a Lebanese-Armenian khachkar artist who runs a studio in Gyumri, and uses medium soft tuff native to Armenia to carve cross-stones, says, “I often add my personal touch to my khachkars combining Christian symbolism with Armenian artistry.” Poladian says that the style of khachkars has evolved. “Earlier, the khachkars were only a cross, then the artists started to add designs and parts of the Bible. It can take up to 45 days to carve a large khachkar. “It’s a lot of work,” she says. “But it’s also very rewarding to see a finished khachkar that I’ve created with my own hands. I want to keep this tradition alive to be enjoyed by the future generations,” she adds.

Arevshatyan, who came to appreciate the profound psychological impact of khachkars with time says, “Unlike the imposing grandeur of churches, these humble stone monuments, offer a more intimate form of spiritual connection for villagers, allowing them to commune with God. The presence of the artist’s name on certain khachkars is believed to reflect the prestige associated with commissioning the work of the most renowned masters. In my explorations, I found myself inspired by Momik, as well, Kiram, whose prolific output of over 80 khachkars stands as an unmatched record in the history of khachkar making.”

In his concluding statement, Babik Vardanyan told us, “Because of the Cross, the stone becomes cross-stone-khachkar, and all my beliefs, faith and emotions are completely reflected in carving the Cross. When my children see me working in the studio, they also sometimes come and start working on the canvas. I think that maybe the day is not far when they will want to continue my work. Love is genetically transmitted, isn’t it?”

From the halls of the British Museum to the bustling galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, these stone sentinels have found a home as an enduring legacy of Armenian culture. So, the next time you travel to a distant corner of the world, keep an eye out for a khachkar. These stone ambassadors may surprise you, standing amidst the unfamiliar sights and sounds, reminding you of the interconnectedness of our world. and the enduring power of art to transcend borders.