The Armenian Weekly. Memory for numbers rarely fails me. I clearly remember a conversation I had with my dear friend, writer and art critic Telman Zurabyan (professor, historian and orientalist from Tbilisi, Georgia) 40 years ago. Speaking of the Treaty of Sevres, he said that within the borders defined by Woodrow Wilson’s arbitration decision, Armenia was to cover the area of 70,000 square miles. The figure immediately aroused my doubt. Professor D.S. Zavriev’s 1946 book “On the modern history of the North-Eastern provinces of Turkey” contains data on the аrеаs of the districts of Western Armenia. It did not take me long to come up with the total. I found that 58 out of the above 70,000 square miles comprise the total area of the Armenian provinces beyond Akhuryan and Araks transferred to Turkey after the Moscow and Kars treaties were signed. One only had to add the area of Soviet Armenia (11,500 square miles) to see where the figure came from.

Telman could not make it up. Apparently, it circulated among the members of the Communist Armenian elite that he had access to as an Armenian radio and television correspondent in Moscow. The question arose, which we can attempt to answer today, how come Van, Bitlis and Karin are considered parts of historic Armenia, while Nakhijevan, Artsakh and the rest of the land, allotted by Lenin and Stalin to the newborn “Azerbaijan,” are not?

In 1966, a few years before my conversation with Telman, the issue of reunification of those lands with Armenia was discussed in the Kremlin, which removes any doubts of its relevance. Alexander Shelepin, then-KGB chief, even urged Anton Kochinyan, then-first secretary of Armenia’s Communist party, to demand the maximum (Artsakh, Nakhijevan and Javakhk were implied). So, why is the term “Turkish Armenia” known to diplomats and historians, while no one mentions Azerbaijani Armenia? To clarify the issue, a brief excursion into our Soviet past is needed.

Russian revolutionary Alexander Parvus stipulated his patronage of the Bolshevik coup by Lenin’s commitment not to raise the issue of the Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire. Only the Ittihad Party (a radical Islamist party in the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1917–1920) could help Parvus obtain the long-desired German nationality, and he could not fail his friends. Lenin kept his end of the deal. The only insignificant exception was the Zimmerwald conference (held in Zimmerwald, Switzerland in 1915 and convened by anti-militarist socialist parties from countries that were originally neutral during World War I), at which the Socialists adopted a purely declarative resolution that did not oblige them to any concrete steps to protect the Turkish Armenians. Everything boiled down to a non-committal condemnation of killing innocent people as bad policy. Genocide was not and could not be condemned. Parvus and his Bolshevik protégés were hungry for money and power regardless of costs. Condemnation of our Genocide was not part of their agenda.

Read also

After the October 1917 coup in Russia, Stalin played even a more sinister role by denouncing in letters to Lenin “the Armenian imperialism,” not the Young Turks’ and Kemal’s Nazism that left two million Armenians dead. It was to Stalin as High Commissioner of Nationalities that Lenin entrusted the responsible mission of resolving all inter-ethnic disputes in Bolshevik Russia. We know how he did that by his handling of the Armenian issues in Moscow and Kars. The peace and “brotherhood” with Kemal was achieved at our expense with a cynical disregard of our aspirations.

Stalin forbade Armenians even to mention their violated rights and desecrated shrines that remained behind Akhuryan and Araks. Complaining about the Turkish atrocities became meaningless in light of the total disempowerment of the Armenians in Azerbaijan and Georgia that the Kremlin declared “fraternal republics.” Any complaint about the gross violations of civil rights of those Armenians automatically entailed a charge of Armenian nationalism, which at those times was tantamount to a death sentence and was dealt with a ruthless efficiency.

The anti-Armenian nature of the Stalinist policy became clear in 1946, when Turkey’s aid to Germany during World War II caused outrage in the West and in the USSR. Attempts by leaders of the Armenian Diaspora to raise the issue of punishing Turkey for its shameful wartime behavior were neutralized by Stalin. In the Russian broadsheet newspaper Pravda (formerly the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), he signaled a campaign for “redeeming the ancient Georgian (a country in the Caucasus region) lands” in Turkey (Kars and Karin were implied), to nullify our claims. Stalin temporized, knowing in advance that President Truman would sooner or later interfere to protect Turkey’s territorial integrity. He did it deliberately to wash his hands of the issue. Soviet propaganda would later explain that failure by Truman’s meddling, not mentioning Stalin’s pronounced reluctance to restore justice (at least partially) for our people. It should also be noted that Truman’s interference was beneficial to our cause, preventing the annexation of the Iranian province of Azerbaijan by the Kremlin. If Stalin had not been stopped, Armenia would have ended up surrounded by two powerful Turkic nations – Turkey in the West and Azerbaijan in the East; that would have been a death sentence to our nation. Stalin did all he could to avoid the redemption of Turkish Armenia at a time when such a solution was not fraught with the danger of unleashing a new world war.

The second round of the fight for vindication of the downtrodden rights of the Armenian people began in the 1960s. Its apogee was 1965, the year of the 50th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, when Tsitsernakaberd memorial was built in Yerevan. The diplomatic tact and patriotism of the then-first secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia, Jacob Zarobyan, played a huge role in making Russia’s public opinion aware of our people’s aspirations (all guests of Armenia visited Tsitsernakaberd and read publications about the Genocide, which gradually removed a semiofficial taboo on mentioning the subject). The Kremlin did not fail to use our irredentism to its advantage, which was quite logical and expected.

It is obvious that by allowing Armenians to talk about the Genocide, the Kremlin hinted to Ankara a powerful lever that could be used to counter Turkey’s pan-Turkic ambitions. Criticism of Turkey by Armenians helped the Kremlin get a firmer grip on the Armenians, forcing them, in case of the Soviet Union’s collapse, to sort things out with a hostile Turkey on their own. This threat is still used by the Kremlin to force Armenia’s compliance with its demands.

All candidates to Communist Party membership in Yerevan were asked the standard and rather stupid question if they approved the sovereignty of Azerbaijan over Nakhijevan and Karabakh. The question was considered tricky, because a negative answer meant the denial of admission. Scolding Turkey was allowed within certain limits, while demanding reunification of Artsakh with Armenia was viewed as sedition and an unforgivable manifestation of nationalism. But let us get back to the Kremlin’s policy. Trifle things like the spurious circumstances of the birth of “Azerbaijan,” assigning it the stolen name of an ancient Iranian province, heritage and territories were of little concern to the Soviets. What mattered was to exert a slight pressure on Turkey; the rest did not matter. Grossly distorted was the timeframe of the Genocide tied to 1915, although it was not a one-time act, but a centuries-old historical process, the apogee of which fell on the period from 1878 to 1923. Equally distorted was localization of the Genocide, limited to Turkey’s territory. The mass massacres of Armenians over the territory proclaimed in 1918 as Azerbaijan was not named the Genocide, although from 1918 to 1920 it left 250,000 Armenians dead. The Soviets found euphemistic misleading misnomers for those horrible crimes, referring to them as “fratricidal Armenian-Tatar massacre” instigated by the Russian Tsar’s secret police. Even Sumgait Pogroms were presented as a triumph of internationalism, not a manifestation of barbarism of the Caucasian Turks. Turkey delegated to Azerbaijan the mission of finishing off the Armenians on the territory Kemal lost control over. Moscow wanted to provide an alibi to Azerbaijan, denying Turkic identity of a non-homogenous and motley conglomerate of tribes that made up the newly invented nation. The Kremlin went out of its way to present “Azerbaijanis” as non-Turks.

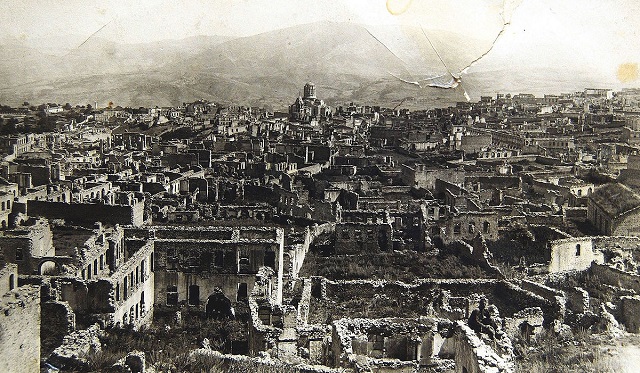

The aftermath of the 1920 massacres of the Armenian population by Azerbaijani forces in Shushi (Public Domain)

The Kremlin removed Azerbaijan from the overall equation or package of the Armenian Question, of which it has been and remains a part to this day. Allowing us to put pressure on the Turks, the Soviets at the same time never prevented the Caucasian Turks from oppressing us. Everything became clear in the years of Gorbachev lawlessness.

The logically irrefutable though not quite evident conclusion from above is that we do not have a holistic and coherent concept of the Armenian Question, and what is presented as such reflects not our interests but those of the defunct USSR and Kemalist Turkey. The time has come to discard, once and for all, the vision that distorts the history of our people. We need a new concept of the main issue of our life, seeing it through our own – not somebody else’s – eyes.

The theses of this article are not new, but they need an appropriate conceptualization. These ideas are analogous to points that should be connected by a line, which should be our line of presentation of the Armenian Question. Let us list them in a logical sequence:

- Extension of the timeframe of the Genocide that lasted from 1878 to 1923 and was not an event that took place in 1915, torn out of the bloody context of our history.

- Extension of the territorial scope of the Genocide that took place, in addition to Turkey, on the territory illegally proclaimed as “Azerbaijan” in 1918.

- Presentation in all venues of the illegal, from the standpoint of international law, circumstances of the proclamation of Azerbaijan’s independence. It was not accepted to the League of Nations in 1918-1920, and it illegally left the USSR in 1991. In this context, illegitimacy implies the absence of Azerbaijan’s right to political existence.

- Introduction of the term “Azerbaijani Armenia” into diplomatic usage (optional).

Of particular note is the third point whose significance goes beyond strengthening our stance in the negotiations on peaceful settlement of the Artsakh problem. The Armenian diplomacy putters with petty themes like recognition or non-recognition of Artsakh, participation or non-participation in the peace process, and compatibility of the principles of territorial integrity and a nation’s right to self-determination. The Gordian knot must be cut, no matter how much the hypocrites frighten us by irremediable or unpredictable consequences of our intransigence.

The category of territorial integrity has nothing to do with the ugly formation that has no right to exist, whose leadership goes out of its way to finish off its indigenous peoples who have lived on their ancestral land for thousands of years, claiming the lands of not only Artsakh but Armenia as well. Azerbaijan does not recognize the right to exist of the Republic of Artsakh, and we demand that its representatives should be allowed to negotiate with Aliyev’s sultanate, the “nation” that has, let us reiterate, no right to exist.

The major weakness of our diplomacy lies in the asymmetry of its response to the scandalous behavior of Azerbaijan. We have more reason not to recognize this quasi-nation than Baku has in refusing to hear the name of the Republic of Artsakh. Azerbaijan is an ugly geopolitical bastard of Turkey, which gives us every right to emphasize that we refuse to deal with it.

Armenia’s refusal of having a dialogue with Azerbaijan must be substantiated. We have documents proving the legal and historical validity of this decision. All that has to be done is just to put them in motion. We can publish the Red or Blue Book, stating the circumstances of the occurrence of so-called “Azerbaijan” in 1918 and 1991, accompanied by the Genocide of its Armenian population. We must stipulate a tough denazification of Azerbaijan as was done with Nazi Germany. After all, what was good for a great nation like Germany cannot be too bad for Azerbaijan. That will be a dead serious no-nonsense talk, not the drooling of a snotty whipping boy.

Denial of Azerbaijan’s right to exist should not be viewed as an extremist demand. We have witnessed the demise of the South African Republic, the USSR and Yugoslavia. Peaceful dismantlement of Azerbaijan by no means implies annihilation of its civilian population. By unleashing the April 2016 war, Aliyev proved that Azerbaijan is a major threat to regional peace and stability. If we are concerned with peace, we must remove the major obstacle to it in our region. Crying a river over Azerbaijan makes no more sense than bewailing the fall of the USSR.

Alexander Mikaelian

Caption: Demonstrators calling on the Soviet Union to officially recognize the Armenian Genocide, 1965 [Photo: Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, Yerevan]