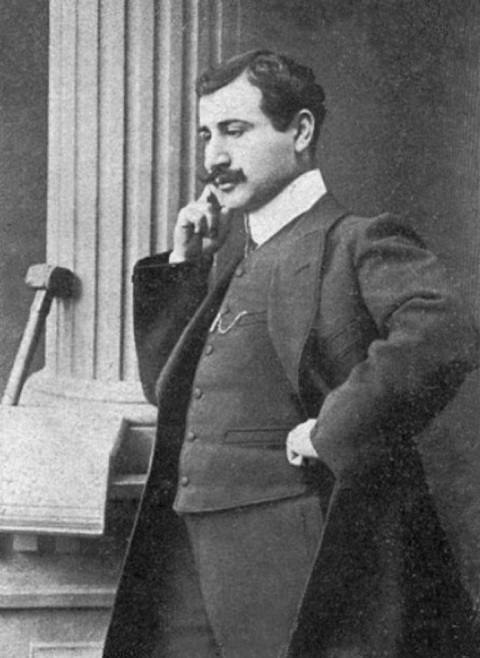

Daniel Varoujan [Taniel Varuzhan] led a short and tragic life. Born into poverty in 1884 in the Prknig village of Sepasdia (Sivas), Varoujan studied at Venice’s Mourad-Rafaelian School before obtaining a scholarship to attend the University of Ghent in Belgium from 1905 to 1909. These were lonely but enlightening years for a young man so far away from his native soil. Five years later in 1914 in Constantinople he would found the group “Mehian” along with fellow writers Gosdan Zarian, Hagop Oshagan, and Aharon and Kegham Parseghian. The group’s name, “temple” in Armenian, referred back to the ancient Armenian pagan gods. In 1915 Varoujan was deported towards Chankiri and gruesomely tortured to death by the Young Turks.

A recent 2019 special issue of Revue Belge de Philologie et d’Histoire [The Belgian Review of Philology and History] sheds important light on the details of Varoujan’s stay in Ghent. It may be the definitive study on the poet’s life during this period. The seven pieces presented here range from anthropological and factual accounts (van Nuffelen and Payaslian, de Messemaeker and Verbruggen) to literary and theoretical ones (Beledian, Nichanian). Some are eloquent and deft, others rather dry and formal. Together they form a fascinating look at the great poet’s life and psyche during the period examined, as well as to the city of Ghent as a whole.

Read also

Varoujan in Ghent was a busy if sometimes desperate young man: he spent long days and nights studying and writing brilliant verse, became an ally of the socialist party, and implored various Armenian organizations abroad to subsidize his tuition and coursework. He took up the cause of working-class factory workers and deplored the supercilious indifference of the upper classes whose members became rich off the labor of others. At first he could not speak any of the local languages — Flemish or French — and was taken aback by the comparatively cold temperament of his hosts.

From Peter van Nuffelen and Simon Payaslian‘s introductory essay, “An Armenian Poet in Ghent-One Hundred Years Later,” we learn that Varoujan was already experimenting and pushing back boundaries, including classic forms of meter and rhythm: “Varoujan rejected the strict adherence to the modes of versification that existed at the time in Armenian poetry. According to him, poetry was the medium through which nature took form and gave expression to the authenticity of (human) thought.” (P. 782, translation mine)

In this introductory essay, the authors discuss the relationship between Belgium and the Ottoman Empire and point to the fact that for Varoujan and his compatriots, Europe remained the cultural example to be emulated. This piece is complemented by Pieter de Messemaeker and Christophe Verbruggen’s “Foreign Students at Ghent University Around 1900.” The latter provides a comparative study on the countries of origin of foreign students in Ghent. It also examines why they found the city an attractive destination for their studies and how they in turn contributed to its intellectual and economic development.

In a sometimes maddening but fairly accurate historical rendering of the treatment of Ottoman Armenians and the founding of a short-lived Armenophile movement in Belgium, Houssine Alloul and Henk de Smaele (“Armenia in the Imagination and Politics of Prewar Belgium”) examine the success of Armenians — or “Oriental Christians” as they were sometimes referred to — in the Turkish empire. They quite correctly allude to the economic jealousy that this success engendered and to the clash between Christendom and Islam. While it is certainly true that depictions of Islam (read: Turks) as “barbaric” by the Belgians were racially biased, the authors at some points come off as apologists for the horrific acts committed by the Ottoman government under Abdul Hamid in 1894-96 and the Young Turks in 1915-1923.

The following essay by Payaslian, “Daniel Varoujan at Ghent University (1905-1909),” is a meticulous examination of Varoujan’s daily life while in Ghent and by extension that of his classmates and friends. The piece is followed by remarkable archival lists of everything from the thirty-nine poems that he wrote while in Ghent to how much he spent on household items such as soap and hair combs, foodstuffs (butter, eggs, milk), rent and every other imaginable expense. This will no doubt fascinate cultural anthropologists and economists, but it may not spark the lay reader’s interest.

Finally in the three literary sections, the authors interpret Varoujan’s work from different if equally fascinating angles. Émerance de la Censerie delivers a classic French explication de texte or close reading of two of Varoujan poems in “The French Poems of Daniel Varoujan or ‘The Heart of the Race’.” She analyzes them in light of established Belgian national history and of the then nascent Armenian national history, while reading the second poem essentially as an answer to the 1909 Adana massacres.

In a somewhat politicized conclusion, the author notes: “This poetry carries with it more than simply an aesthetic value; its goal, its duty even is to make readers think and to remind them that the troubles of the Armenian nation will continue to be a topic of discussion and that the recognition of the Armenian Genocide remains an ongoing battle.” (p. 883, translation mine)

The noted writer and theorist Krikor Beledian then gives a delicate and nuanced analysis of Varoujan’s poems. In “‘I have seen Europe,’ Daniel Varoujan: The Time of the Destruction of Images,” he astutely points out that Varoujan’s oeuvre is structured around “the experience of the foreign” and is essentially pictorial in nature. Varoujan describes the colorful Venice of his early youth in sensual terms (“Venice the blue city, the glorious Grande Dame”) and compares her to a courtesan “draped in aquatic ribbons” (p. 893)

Beledian also notes that Varoujan exalts the Armenian people “only because it is about to die.” (p. 906) Towards the end of his essay he wonders whether the pictorial nature of Varoujan’s poetry can survive the terrible massacres that took place in Adana in 1909. His nuanced analysis is a perfect lead-in to the seventh and ultimate essay in the piece, Marc Nichanian’s “Mourning and the Gods.”

A former professor at Columbia and Sabanci Universities, Nichanian has developed a fascinating theoretical framework for his analysis of the genocidal impulse in his seminal Writers of Disaster, based in part on an analysis of the concept of the witness and the interdiction of mourning. Nichanian’s current essay revolves around the fact that Varoujan has heretofore been read as someone who glorified the past in his reference to the ancient Armenian deities: “We try to read him as a poet of mourning, who needs to be understood within a double context: the one of the 19th century philological reinvention of mythology, and the one of an ongoing national disaster, which he himself mysteriously called the “nothingness of fatherland.’” (p. 933)

Nichanian sees Varoujan as the ultimate poet of mourning: one who mourns the passing of the past gods but also the death represented by what Nichanian terms the “national disaster.” In light of current events in Armenia, it is a prescient and chilling message.

N.B: the essays in question were published bilingually in French and Flemish in the Journal, with abstracts in French, Flemish and English. Textual translation of both the authors’ words and Varoujan’s are strictly mine and I bear responsibility for any inaccuracies that result from my own negligence or lack of time.

To access the archives of Revue Belge de Philologie et Histoire/ Belgische Tidschrift voor Filologie en Geschiednis, go to: www.rbph-btfg.be