NEW YORK — Filmmaker Atom Egoyan and composer Mary Kouyoumdjian have partnered with the Metropolitan Museum of Art and created an original work titled “They Will Take My Island,” about the late painter Arshile Gorky.

The premier performance took place virtually on January 26 on the Metropolitan’s website, as well as its YouTube and Facebook channels.

Read also

It features footage shot for but not seen from Egoyan’s 2002 film “Ararat” and the documentary “A Portrait of Arshile,” accompanied by music and spoken words, by Kouyoumdjian.

Kouyoumdjian’s haunting score, specifically written for this event, is performed by the JACK and Silvana quartets.

It is the first performance of the 2021 MetLiveArts virtual season. The performance is free and will remain online indefinitely.

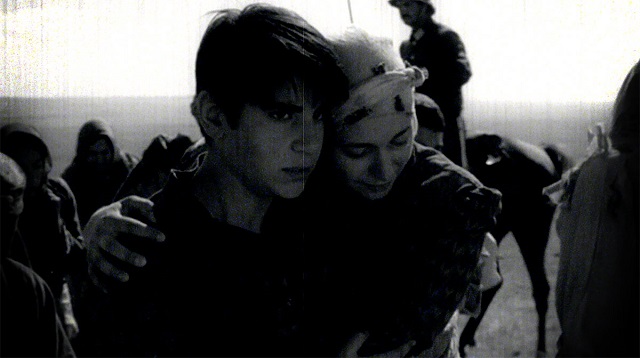

Egoyan’s interest in Gorky runs deep. His film, “Ararat,” told the story of the Armenian Genocide, in part through the eyes of the young Armenian refugee who later reinvents himself as Arshile Gorky in the US.

In an expansive interview this week, Egoyan, an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker with a string of introspective films as well as lush opera productions and installations, has found a way to combine his heritage with a non-linear approach to art.

“Gorky is one of our greatest visual artists,” he said, adding “he is clearly, in terms of American contemporary art, hugely important.”

“He was one of our most important survivors of the Armenian Genocide,” he added, along with Komitas.

The two were “creative forces that needed to survive catastrophe” and in that way, contribute to the canon of world art.

Kouyoumdjian, Egoyan’s collaborator in this program, in an interview said she was thrilled to collaborate with the Canadian filmmaker.

“I have been such a big fan of Atom Egoyan since I was a teenager,” she said.

She had sent him a letter and asked for him to collaborate with her, and she said to her surprise, he had replied positively.

“It was incredible that he had awareness of who I was,” she recalled.

Aside from mutual admiration, she explained that both she and Egoyan have been influenced greatly by the life and work of Arshile Gorky.

Egoyan said he was delighted when Kouyoumdjian approached him for the Metropolitan project.

“It is great to have the support of the Met,” he added. “How does anyone really apply themselves to an art work? The Met did have the major exhibition ‘Armenia.”

One of the reasons Egoyan was thrilled to work with Kouyoumdjian was her libretto on Egoyan.

“We were committed to the idea of working together,” he said. “It was a way of going deeper into the character.”

The program also includes interviews with Saskia Spender, granddaughter of Arshile Gorky and President of the Arshile Gorky Foundation; Parker Field, Managing Director of the Arshile Gorky Foundation; and Michael Taylor, Chief Curator of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

“We were hoping to present it on stage and use the museum for an expansive production of this piece,” Egoyan said.

Reinventing Vostanik

In addition to his obvious talent and tragic backstory, Gorky’s fascination lies in his mystery, Egoyan said.

Gorky’s life story is like a work of fiction, with highs and lows that are almost beyond human endurance. He was born in Van in 1904 as Vostanik Adoyan, survived the Armenian Genocide, saw the death from starvation of his beloved mother, and after arriving in the US and reinventing himself as Arshile Gorky, a relative of writer Maxim Gorky, became a trailblazer of 20th-century American abstract school of painting along with Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. A tragic car accident, a devastating studio fire and the end of a troubled marriage drove him to suicide in 1948.

(Interestingly, Maxim Gorky itself was the pen name for Russian writer Aleksey Maksimovich Peshkov.)

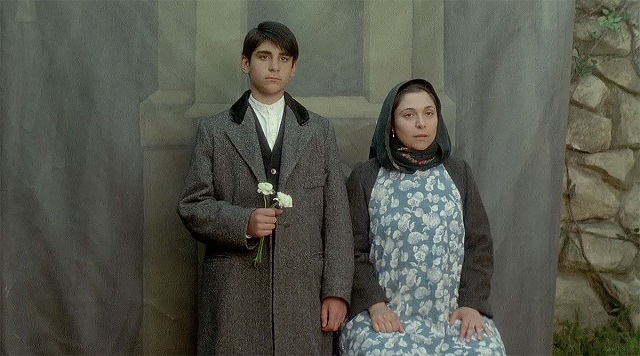

During his short and tragic life, again and again he returned to the photograph taken of him and his mother before the Genocide.

“The Armenian Genocide was so appalling,” Kouyoumdjian said.

The processing of that event, and his role as survivor, she said, led to so much of his art. His life, she said, “offers a lot of insight into what people had gone through.”

Egoyan concurred: “He was dealing with a past trauma and that led him to reinvent himself.”

Scene from “Ararat” in which the adult Arshile at his studio works on a painting based on his photo with his mother

A Painting Casts a Spell

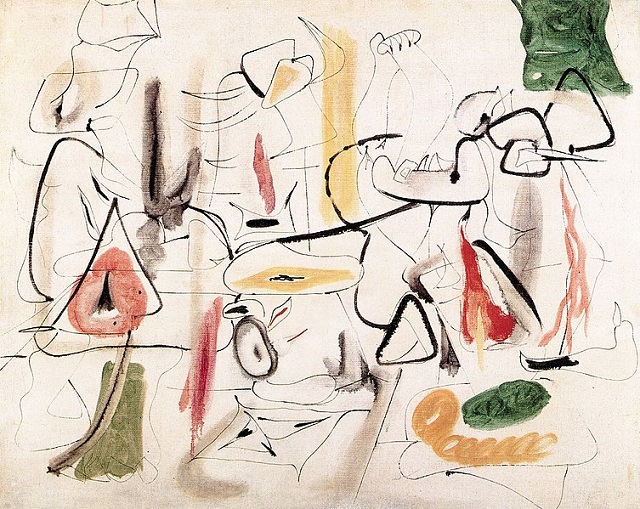

The painting “They Will Take My Island” was the first painting of Gorky that Egoyan saw; it hangs in the Art Gallery of Ontario.

“It has such an evocative title,” Egoyan said.

The title of the painting, Egoyan said, is particularly poignant now, after the disastrous war launched against Armenia and Karabakh, which led to the loss of a good portion of the latter.

“It has a strong meaning for me, especially in light of what we have experienced,” Egoyan said. “We had no idea how much it would reverberate.”

Both he and Kouyoumdjian said they really loved the titled of the painting.

“It’s a beautiful title” with “an added significance.”

At the end, “We are left to wonder,” Kouyoumdjian said.

The Met program includes “really crucial images from” his film “Ararat,” including a deleted scene in the Armenian language between Ani, played by his wife and frequent collaborator, actress Arsinée Khanjian, and Gorky, in his studio. In the scene they are talking about this reincarnation as Gorky in the US.

“I am delighted to finally present this scene,” Egoyan said.

Kouyoumdjian added, “He [Gorky] kept coming back to the photo. There must have been so many feelings and thoughts. The loss of his home and his identity. What he could not say during the Genocide, he returned to in order to express himself.”

“Gorky did express the same image repeatedly. I can relate to it as well,” she noted, adding that “for the past 20 years, most of my work has centered on the Armenian Genocide.

In addition, it includes scenes from “Portrait of Arshile,” which Egoyan explained, is a love letter of sorts in the form of a short film, addressed to his son with Khanjian. “We wanted to describe to our son why we had chosen to name him Arshile,” he said.

The Met project “is a very different way to work,” he said. “Something really developed organically.”

“This is a collaboration unlike anything I’ve done before,” Kouyoumdjian added.

“It was a dialogue between the two of us,” he said, explaining that as diasporan artists he and Kouyoumdjian could offer a specific point of view.

Kouyoumdjian said that Egoyan would share clips and she would compose based on those.

In addition, the project features the voices of several experts on the works of Egoyan, including his granddaughter.

Said Kouyoumdjian, “Normally I write a lot of music for film. Atom had given me access to his films ‘Ararat’ and ‘A Portrait of Arshile.’ I took excerpts of audio and edited them into the music. I sent Atom the mockup of what the music would be. He and his editor created films for that music. It was a really interesting collaboration. I scored music to that story so that the music would serve the text best.”

It is especially heartbreaking to think about the “ancient monuments that are being desecrated once again,” he added. The images of the attacks on the Nakhijevan monuments were fresh in the minds of Armenians, but already, a whole host of new photos and videos of attacks on Karabakh’s historic monuments are being released.

At the same time, he painting and sketched many versions of the 1912 photograph that was taken of him and his mother, possibly influenced by frescos of the Madonna and Jesus that he would have seen.

Egoyan noted that initially when the Metropolitan Museum approached Kouyoumdjian and him to put together the program, it was meant to be a spread-out series of events and concerts. The pandemic, however, forced the two to come up with a new virtual format.

The Metropolitan Museum has on exhibit one painting by Gorky, “Water of the Flowery Mill.”

Armenian Genocide’s Shadow

Aside from creative outlets as diasporan artists, what unites Egoyan and Kouyoumdjian is their connection with the Armenian Genocide.

Egoyan’s grandmother was orphaned during the Genocide and later ended up in Egypt.

“Her sorrow seeped through to [her son] my father, who was an artist,” he added. In fact, both his parents were painters who met in Cairo as students of teacher and artist Ashot Zoryan. (Art is a family business for the Egoyans; his sister, Eve, is a concert pianist.)

His father’s “tremendous sense of grief” was expressed through his art. In fact, he said, the first time his father visited the Tsitsernakabert Armenian Genocide Monument in Yerevan, “he had a psychic breakdown when he saw the structure, the pillars … which took him back to that moment.”

Preserving memories — the past — is a theme Egoyan frequently revisits, as well as addressing the distortion of history. The pain makes it so that “there are answers that can’t be pondered,” he explained.

This theme, he said, applies to his movies that do not deal with the Armenian Genocide, such as 2013’s “The Devil’s Knot,” with Colin Firth and Reese Witherspoon, about the “communal horror” that grips a small, rural American town after the murder of several children.

History and immigration as well as the Armenian Genocide have shaped Kouyoumdjian’s viewpoint, also.

“When my parents came to the US, they had no people here. So there was a lot of pressure growing up to preserve the culture. Growing up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, here I was pushing against all those things. When I moved away from home,” however, she explained, she started to appreciate what she had been rebelling against and embraced it.

Another influence of the Armenian Genocide, she said, is the idea of survivors’ guilt, something that she said fascinated her.

“Part of it has meant that because I am in a position that I can speak out, I feel it is my responsibility to do so,” she noted.

The composer noted that her grandparents were survivors of the Armenian Genocide and they eventually ended up in Lebanon. “As a grandchild who lives in the US and [not worried about ] a lot of risk exploring this.”

Kouyoumdjian often mixes voices with her classical compositions, which are often influenced by Armenian folk melodies. In 2015, for the Genocide centennial, she created music for the Kronos Quartet.

“We took the pieces to Yerevan, where we interviewed with survivors. When audiences hear things … from human voices, it hits a little differently than if it were only music,” she said. “It invites empathy from the listener.”

Importance of Art and Monuments

Egoyan said he was happy that the project was finished before the recent disastrous war.

“I hope our holy sites are preserved but we are incredibly fearful,” he noted.

Egoyan said that one of the factors that drew him so deeply into the late artist’s world was an essay by Peter Balakian, titled “Arshile Gorky: From the Armenian Genocide to the Avant-Garde.”

Egoyan said that he “tends to go back to images and reexamine and reframe them,” he said.

He also used footage from an Armenian protest in front of the Turkish embassy and other material. All the footage was eventually transferred to 35-millimeter film and shown later as part of the Venice Biennale among others.

“We need to instill in ourselves that our culture matters and that it can also matter to others,” Egoyan said.

In case of Gorky, he said, it was interesting that Gorky was running away from his history as it was too traumatic for him, but “his horrifying history was so woven into his work.”

Artists like Komitas and Gorky, he said, “transmit the core of our identity. We have a responsibility to preserve those and as artists to keep them alive.”

Asked Kouyoumdjian: “There is so much culture and art that was destroyed. How do we move art and culture forward?”

Other Projects

Egoyan stressed that it is not always the dark side of humanity that interests him; he takes on the jolly side when he works in opera, including the Canadian Opera Company’s production of Mozart’s “Cosi fan Tutte,” to which he brings “joy and lightness.”

Egoyan is working on various opera projects that have been pushed back because of COVID to 2022 and 2023, and two film projects are also in the running.

“Death in Venice” by Benjamin Britten for Pacific Opera Victoria and Richard Strauss’s “Salome” for the Canadian Opera Company.

When you make a film you think wider, about who will see the film, he explained.

Kouyoumdjian has received commissions for such organizations as the New York Philharmonic, Kronos Quartet, Carnegie Hall, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Beth Morrison Projects/OPERA America, Alarm Will Sound, among others. Her work has been performed internationally at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MASS MoCA, the Barbican Centre, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), Millennium Park, and more. She has also worked on the soundtrack of the movies “The Place Beyond the Pines” and “Demonic.”

She is currently finishing her doctorate at Columbia University; she holds an M.A. in Composition from Columbia University, an M.A. in Scoring for Film & Multimedia from New York University, and a B.A. in Music Composition from the University of California, San Diego.

Kouyoumdjian noted that has made a resolution to do more things that scare her professionally, in order to expand her horizons.

She has collaborated with the Metropolitan before. A couple of years ago, she recalled, she was commissioned to write for the soundtrack to be performed live at a showing of Sergei Paradjanov’s “Color of Pomegranates.”

For more information about Atom Egoyan and his past and future endeavors, visit http://www.egofilmarts.com; for information about Mary Kouyoumdjian, visit http://www.marykouyoumdjian.com/.

To watch “They Will Take My Island,” visit the museum’s website https://www.metmuseum.org/events. The program will be up indefinitely.

Main caption: Atom Egoyan (Ulysse del Drago photo)