A useful reference to world experience

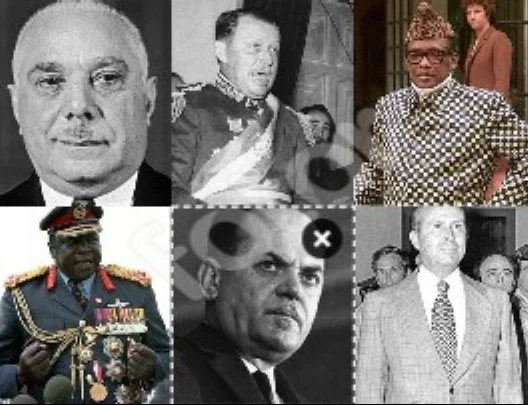

Armies are very different in all respects, but there is no country in the world where the people do not like their army, even if we consider some countries to be exceptions and instances in certain time periods where soldiers became instruments of repression or a ‘supreme court.’ In all countries, the army is the birth of the people and an inseparable part of the people, and the Republic of Armenia is not an exception by any means. However, there is no country in which the army’s attempts to interfere in politics have not ended in tragedy and have not pushed the country and society back from the normal path of development, even in the case of Pinochet, whose dictatorship was accepted in some circles as ‘good.’ We know the consequences of the army interfering in politics in Africa and Latin America. The names Rafael Trujillo, Fulgencio Batista, Alfredo Stroessner, and Anastasio Somoza became symbols of dictatorships and suppression, and the names Idi Amin and Jean-Bedel Bokassa are synonymous with madness and cannibalism. However, the military’s intervention in politics had one purpose in all cases- a political vacuum and the practical inability of the political class, which created the illusion that ‘the army will come and establish order.’ And life has shown what kind of ‘order’ and ‘rule’ have been established as a result of disasters and nightmares, after which it took years to restore civil and democratic power.

It is generally accepted to follow the European examples in all confusing situations. Everything that took place in Spain in the 1930s, for example, is considered a junta or fascism. And the Regime of the Colonels in Greece (1967-1974) turned into a perfect nightmare for the Greek people. With the backdrop of the Cold War, right-wing populist generals had unique methods of ‘saving their homelands from communism.’

The story is silent about the direct support of the United States, but it is known that the Greek junta was fulfilling its allied obligations and adhering to its mission to resist communism, and Washington tended to look at many things through blinds. Relations with Turkey, which has a history of military coups, have been strained, and it is not difficult to imagine how this has been used by both sides to falsify domestic political issues. And it all had a rather sad ending. Dimitrios Ioannidis, who replaced his predecessor, Papadopoulous, a junta leader, in another revolution, created an adventure in Cyprus by ousting the legitimate president of Cyprus, a freedom fighter for Cyprus’ independence and an advocate of Cyprus’ union with Greece, Archbishop Makarios, during his one inglorious year of rule by accusing the archbishop of ‘extra reverence’ towards the communists due to his tolerance. The Greeks ironically called this military coup a ‘black major’ coup. These heinous regimes led to a fiasco- the catastrophe of the Turkish army invading the northern part of Cyprus and the genocide of the Greeks in Northern Cyprus. And the junta leaders of the ‘black colonels’ were sentenced to life imprisonment and died in prison. Some of them spent decades in prison, such as Ioannadis, who died in 2010. However, no matter how ‘rich’ Russian history is with bloodshed, during the entire history of the Russian Empire, the Russian military elites have never gone against the government, whether it was tsarist, communist, or post-Soviet. The post-Soviet European countries, in joining the OSCE and the Council of Europe, have undertaken obligations that are also outlined in their constitutions, according to which the army must stay out of politics and under civilian control. That is not an issue of taste or political preferences. It comes to confirm the experience, the brief reference of which proves that it can be catastrophic for people. This conversation, of course, does not come from thin air for it to have been modernized in Armenia, and it is not too much to think about it once again. Armenia is definitely not an exception to this if the ‘Pandora’s box’ of military coups was opened there as well. After a while, the generals will want to ‘overthrow’ the majors, the majors will want to overthrow the captains, and we will reach the end of the sergeants and the state (not to be confused with Tigran Sargsyan’s lectures, in which he delivered a speech on ‘the end of the state,’ but it was about something else).

Read also

Yes, sergeants have also carried out a revolution, such as master sergeant Samuel Doe in Liberia in 1980. The ‘field commanders’ killed him ten years later during the civil war that had broken out during the sergeant’s ‘salvation’ activities. Of course, there is one way to avoid this very possible nightmare: the toolkit of democracy enshrined in the Constitution and the political will to use it. That is, elections in which all subjects ‘play’ by the same democratic laws, and the military continues to perform its direct duties while enjoying the love and respect of the people. Of course, it is indisputable that the Constitution simply excludes the military from politics with a text, but this reference is also aimed at showing what such temptation can lead to. Over the past thirty years of independence, an extremely important tradition was established in Armenia in which the army does not interfere with politics, aside from the tragic events of 2008 when the army was dragged into politics. That one incident was rejected by society, and as far as what catastrophes the new opposite ‘tradition’ can bring upon Armenia- read above.

Ruben Mehrabyan

Pictured: Top (from left to right)- Trujillo, Stroessner, Mobutu, bottom (from left to right)- Idi Amin, Papadopoulos, Ioannidis