by Arpi Sarafian

Cultural memory as “Resistance to Erasure” has been a recurring topic in the Armenian press lately. The tragedy of Artsakh and the fear of further loss of our ancestral land has made the focus on erasure inevitable. It could be argued that if we cannot hold on to the land, we can at least hold on to the memory of the place by preserving its cultural heritage and by keeping alive our identity as Armenians.

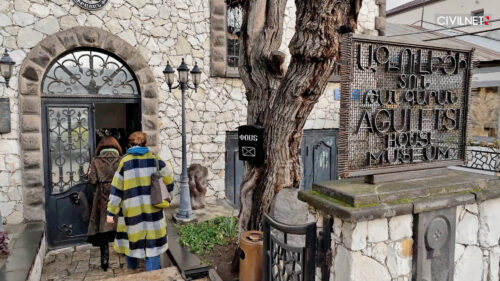

One such recent attempt is the “House Culture” series on Armenia’s House Museums produced by CivilNet, one of the leading media outlets in Armenia. There is indeed something unique about visiting a House Museum. Immersing oneself in the everyday life of an artist, while experiencing the richness and the beauty of a lived history, creates a strong desire in the viewer to protect the legacy and to pass it down to future generations.

Read also

The series comprises five short films hosted by writer and filmmaker Christopher Atamian who was invited to Armenia by CivilNet to write, narrate and to co-produce the films. These films take us into the most intimate space, the home, of five of our most revered poets and artists. The stories, written by Atamian in his signature elegant style, are packed with fascinating details about the artists and the times they lived in. These narratives resonate with us because they make our tragic past relevant to our current reality of loss and displacement.

Each video in the series excels with its beauty and is a favorite in its own unique way. The elegance of the original furnishings in the Yeghishe Charents House Museum, kept as they were arranged in the poet’s lifetime, is unmatched. The peaceful picturesque village of Zangakatun, where Paruyr Sevak was born and where he spent his youth, brings one even closer to the purity and the beauty of the poet we all adore. Avetik Isahakyan, whose poems have become the lyrics of many of our popular songs, lures us with his lyricism and his insights into the truths of life.

All five stories touch the viewer deeply. The in-depth knowledge of the museum directors and the researchers interviewed in the films, their articulateness and their passion for what they do jump out at the viewer and evidence that the memory is still alive. Beautiful cinematography also greatly enhances the stories. Atamian credits the camera persons (Tigran Margaryan, Gevorg Haroyan, Ani Balayan), the editor (Ani Balayan) and the producers (Hasmik Hovhanissyan, Maria Yeghiazaryan, with Salpi Ghazarian as supervising producer) for the successful outcome of the series. “Ultimately it is thanks to the team in Yerevan that they turned out so well,” he affirms.

Perhaps closest to my heart is the footage depicting the anthropologist and artist Lusik Aguletsi, displaced from her village of Verin Agulis in Nakhichevan, the enclave in Armenia ceded to Azerbaijan by Soviet Russia in the early nineteen twenties. One would think that the portrait of an unknown woman — unknown to me at least — would fade against the startling originality of the visionary filmmaker Sergei Parajanov or the energy of every Armenian’s beloved poets Charents and Sevak. Yet, Lusik stands tall amongst these giants of enormous power and influence.

In fact, the Aguletsi segment introduces a distinctly new dimension into the series. It adds a charm that is feminine in the subtlest and the most beautiful sense of the word. Atamian’s story evokes the mystique of a woman who risked her life to make sure that the threatened artifacts from her native Nakhichevan survived when so much was being lost and destroyed. The display in the Museum of the more than one thousand precious recovered objects, the colorful carpets with their exquisite designs, and Lusik’s own beautiful paintings adorning the walls totally captivate the viewer. The delightful wood and straw puppets symbolizing religious and various other holidays further lure the viewer to the ethnic Armenian lore the ethnographer dedicated her life to preserving and to promoting.

The dim lighting, the reds, the gold, and the shades of brown and maroon that dominate the interior of the Aguletsi Museum evoke a certain spirituality. Lusik believed that cleansing one’s spiritual world was important. The soul needs to be pure, she said. And to learn that she actually wore the beautifully displayed traditional dresses — the daraz — and the jewelry as her everyday attire adds yet another layer of otherworldliness to the viewer’s experience of this remarkable woman.

Aguletsi’s story also evidences that peaceful coexistence is possible. Lusik’s grandmother, we learn, taught Armenian needlepoint techniques to her Azeri neighbors in her village in Nakhichevan. One can only hope that a woman’s more compassionate and gentler nature—attributes historically regarded as feminine—will help steer mankind away from the mentality that makes wars possible.

In the context of our current reality of endless wars and of the historical exclusion of women from public life, it is no coincidence that women have been at the heart of the conversation. There are studies of the experiences of women in Medieval Armenia who, while underrepresented, had valuable insights to offer their communities. The newly published Last Night on Earth: Stories from Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine utilizes the graphic format (comics) to look at “war through women’s gaze.” Especially significant is the research into the transformative role of women in their society’s survival, both in times of war and of peace.

Bringing women in would in fact dismantle the male-female opposition and the ensuing system of domination and subordination that inevitably leads to wars. In a strikingly bold essay, “The Role of Armenian Women in War and Peace: From Artsakh to the Present,” human rights activist Nurisa Erismis from Denizli, Turkey, with maternal roots in Yerevan, portrays women as “an invisible frontline that kept life going.” “The story of Armenian women is, in truth, the story of all women who carry the burden of wars they did not start. . . . Perhaps the greatest political revolution of our time will be when women become not the casualties of war but the strategists of peace,” writes Erismis.

Women have also been making headlines with their award-winning documentaries. Emily Mkrtichian’s There Was, There Was Not portrays four women in Artsakh as unique forces in their community, in her words, “carrying its spirit forward in their daily lives, even after losing everything material that once defined home.”

Nonetheless, as powerful as storytelling can be in helping us survive, the connection to one’s land remains. Who can forget the thrill of that special feeling of belonging and of security that setting foot on one’s native soil gave one? We may build new homes in every corner of the world, but we still fight to keep our land. That our ancestral land, Artsakh, is no longer ours to claim deeply saddens us. That sadness must be the strongest evidence that the memory is still alive, and that we shall overcome all challenges and endure. The twenty-seven House Museums in the Republic of Armenia, “celebrating the creators who shaped the soul of this extraordinary nation,” to borrow Atamian’s words, are a living tribute to the Armenian people’s ongoing creativity.

Experience all five films in the series on YouTube:

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXdQDGiVF4c&list=PL1GXE7tjLboI_0Jt7KaWKYYRrH1KGZCFf)