The International Crisis Group. Armenia’s struggle to integrate over 100,000 refugees who fled Nagorno-Karabakh when Azerbaijan seized back control of the territory in 2023 risks undermining the country’s efforts to unite society behind its push for a lasting peace with Baku.

Since fleeing their home in Nagorno-Karabakh two years ago, Karine and her family have struggled to make a new one in Armenia. They sleep in the same room of a ramshackle two-room house, with two adult sons sharing a fold-out couch. It is a big step down from the spacious village house they left behind, surrounded by vegetable gardens; their chickens, pigs and cattle; and forests rich with prey for hunting. The family were among 100,000 ethnic Armenians who made up virtually the entirety of Nagorno-Karabakh’s population and were displaced when Azerbaijan retook the territory in 2023. For nearly two years, they had relied on a government subsidy to cover their rent and utilities in Armenia. In June, that support ended.

While the Armenian government successfully handled the initial influx of Karabakh refugees, the difficulty of integrating them more fully into Armenia has become a source of political friction. Tensions have been on the rise as the safety net for refugees frays. “When we first came, the government helped us a lot”, Karine said. “But most of us have spent all our savings, and now the government has cut the assistance. This winter will be very, very difficult for Karabakhis”. Barely able to make ends meet, the family hopes to move again, most likely to Russia.

Opponents of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan have attempted to use the plight of refugees as a tool in their struggles with him, leading to a furious reaction from the ruling party. Pro-Pashinyan media and some of his political allies have harshly criticised Karabakh Armenians, accusing them of being ungrateful pawns of the Armenian leadership’s political enemies. “Armenia didn’t create this crisis”, an analyst close to the government said. “It’s unfair that Yerevan is left to manage the consequences”.

Read also

Since Azerbaijan regained control of Karabakh in 2023, Pashinyan has tried to reach a peace agreement with Azerbaijan. If peace efforts succeed, it could end a conflict that dates to the Soviet Union’s collapse, when Armenian forces took control of Karabakh (a majority-Armenian former autonomous territory in Soviet Azerbaijan) as well as large swathes of surrounding Azerbaijani territory. As part of the negotiations, Pashinyan has renounced any Armenian claim to Karabakh and avoided issues related to the displacement of Karabakh Armenians, such as their rights to the homes, cultural heritage and graves they left behind. Thanks in large part to the prime minister’s commitment to pursuing negotiations with Baku, the long-time foes have made significant diplomatic progress. They have finalised the text of a peace agreement, though it remains unsigned, pending changes to Armenia’s constitution that Azerbaijan is demanding. With U.S. support, Yerevan and Baku have also started work on reopening transport routes between the two countries.

But the rush to peace has left Karabakh refugees feeling abandoned – economically, politically and morally. If these tensions remain unaddressed, the displacement from Karabakh will remain an open wound in Armenian politics and society.

Karen, a pensioner living in a village on the outskirts of Masis, says the reduction in government aid has forced painful choices, as many displaced Karabakh Armenians struggle to afford basic necessities. October 2025. Marut Vanyan for CRISIS GROUP

A New Home

Beyond the difficulty refugees have in letting go of what they left behind in Karabakh – discussed further below – the biggest challenge they face is finding adequate and affordable housing. The government’s efforts to help refugees afford new homes have foundered, and many refugees perceive the ineffectiveness of housing aid programs as indicative of lack of interest in their well-being.

The Armenian government’s subsidy to help refugees pay rent – about $130 per person per month – rolled out shortly after the refugees arrived. The support allowed people to get by, but it did not make life easy. The limited amount forced refugees to make a difficult choice about where to live in Armenia: the capital city, Yerevan, has the highest rents (which had already spiked as a result of the influx of Russians who fled there following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine) but also the best employment prospects. Elsewhere in the country, housing prices are lower, but work is scarce.

Like many refugees, Karine’s family made a compromise, choosing one of the small cities surrounding Yerevan, where rents are lower than in the capital, but residents have access to jobs in the city. Their choice, Masis, less than an hour from Yerevan, is one of the most popular landing spots for refugees: about 17,000 have settled here. Their little house on an unpaved road costs just under $400 a month, meaning that the aid they received at first covered the rent and utilities.

The curtailment of the rental aid program, announced at the end of 2024, sparked the largest refugee protests since the mass exodus in 2023. The following March, thousands gathered in central Yerevan to protest the aid cut, which was scheduled to go into effect in April. In response, the government delayed the reductions by two months. But, in June, the cuts did come. Aid rolls have now been trimmed to 45,000 recipients – comprising refugees from vulnerable groups like children, pensioners or people with disabilities – who receive roughly $80 per person a month. This program, too, is scheduled to wrap up. Termination is planned for January 2026, though a government official said it might be extended through the end of winter. Karen, a pensioner who lives in a village on the outskirts of Masis, said he stopped buying sausage after June. “Now we just eat bread”, he said.

Many refugees began moving out of the country when rental aid dried up in June, most often to Russia, where the cost of living is lower and many Karabakhis already live. According to a city official in Masis, the refugee population – which already had been declining – dropped by more than 20 per cent or at least 4,000 people. In total, official statistics suggest that about 16,000 refugees have moved out of Armenia since 2023; officials from the former Karabakh de facto government say the figure is at least 24,000 and probably much higher.

The government’s stated rationale for curtailing rental aid was to push people to avail themselves of another program: a one-off, lump-sum payment to purchase a home. The government hoped that program would nudge refugees to settle in Armenia permanently. “We need them to decide. Are they going to restart their lives in Armenia or not?”, the government official said.Few have taken advantage, largely because many refugees consider the payment insufficient. Under the scheme, each refugee (including children) is eligible for $8,000 to $13,000 to buy a home, and families can pool their allotments. But the amount varies depending on how close the home is to Yerevan, with the government offering more to those willing to live in remote areas. In practice, the amount given for Yerevan is often too little to buy there. (One exception is families with many children, though these people tend to have lived in rural areas in Karabakh. Middle-class urban families, who often have fewer children, are now priced out of Yerevan.) While the aid is enough to buy a home in the countryside, families are running into the same problem those participating in the rental aid initiative encountered: after decades of uneven development, there is very little work for new residents outside the capital. The government official acknowledged that there was “no interest” in the home purchase program until rental aid was cut.

Despite the massive cost of the initiative, toward which they plan to put over $2 billion overall, government officials argue that they are not constrained by a lack of funds, including because international donors have contributed tens of millions of dollars in aid. They say, not unreasonably, they are worried that increasing the amount allocated for purchases would create “fluctuations in the real estate market and artificial price inflation”. “The amount is set in accordance with real estate market values”, said one official. Many refugees, too, note that home owners are raising prices, mindful that refugees are getting subsidies.

There are other hurdles to home ownership beyond cost. To receive aid, prospective buyers must obtain Armenian citizenship. But many refugees are unwilling to apply. Though the de facto government of Nagorno-Karabakh was never recognised by Armenia, or any other state, residents had Armenian passports which included a code, 070, marking them as coming from Karabakh. Many thought the passports meant that they were already citizens of Armenia. Yerevan says these were only travel documents and that Karabakh Armenians must now apply for Armenian citizenship under a streamlined two-month process. But many refugees fear that giving up their 070-marked documents will render them ineligible to return to Karabakh or get compensation for their property, should mechanisms to facilitate either emerge. Experts point out that international law will protect their rights in this eventuality, but the worry is nevertheless widespread.

As noted, interest in the program is so far low. Of some 25,000 families eligible, only 3,810 families had been issued certificates to buy homes as of mid-December, a government official told Crisis Group; of that number, 1,631 families had actually bought a house. Government officials say the purchases demonstrate that the payments are indeed adequate. But refugee advocates say low participation rates reflect the difficulty in finding a suitable home for the money offered. In a sign of the mounting mistrust between the government and refugees, many of the latter suspect the program is designed to encourage them not to settle but to leave Armenia. In reality, however, the program’s flaws may be a function of being hastily designed with insufficient input, including from experts and refugees.

The government is now tweaking the aid programs to make them more responsive to refugees’ needs. At the end of November, it announced it was considering paying rent for ten years for households of three or fewer people; bigger families would still not be eligible. An aid official, though, recognised that these efforts will not bring down the price of housing, which is the biggest challenge for refugees. Partial fixes identified by this official and other advocates – such as adjusting aid allotments for inflation or constructing “social housing” for refugees and others who need housing support – would need to be carefully calibrated to avoid spurring inflation, distorting markets or committing the government to long-term expenditures that it would struggle to support.

Residential buildings in Masis, where housing is cheaper but economic prospects remain fragile. October 2025. Marut Vanyan for CRISIS GROUP

“Hate Speech”

The refugees also are contending with social tensions. Despite Armenians’ strong cultural and historical attachment to Karabakh, the influx of refugees stirred up latent resentment among Armenians from Armenia about the centrality of Karabakh in their politics. Many men, especially, had bad experiences in Karabakh during their mandatory military service, living far from home, in difficult circumstances and subject to the hazing endemic in the Armenian armed forces. In the worst cases, families lost parents, children or other loved ones in the multiple wars over Karabakh. Armenia’s government for decades propped up the de facto authorities of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic (NKR), including paying salaries of government employees that were much higher than those in Armenia, widely believed to be an incentive for residents to remain in the enclave. Until Pashinyan came to power, Armenia had been ruled for two decades by figures from Karabakh, including former Presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, a period many remember as corrupt and authoritarian.

Refugees now often say they feel unwelcome in Armenia. Refugees in Masis said strangers have told them Karabakh Armenians should have put up a fight when Azerbaijan attacked in 2023. That allegation rankles Karine. “Ordinary people are not politicians. Pashinyan gave Karabakh to Azerbaijan. They should blame him, not us”, she says, echoing sentiments shared by many Karabakhis. On social media, the vitriol is worse. A refugee who has a podcast aimed at preserving the Karabakh dialect says she gets abusive comments on the podcast’s Facebook posts, with one person writing: “Don’t bark your dog language in my Armenia”.

Officials in the government, Pashinyan’s Civil Contract party and media connected to the ruling party have echoed the negative rhetoric. Officials have claimed that refugees are insufficiently grateful to the Armenians who received them in 2023 and argue that refugees who express discontent are political “cannon fodder” being manipulated by the opposition and Russia. The phenomenon of denigrating Karabakhis has become known as “hate speech” (Armenians use the English term), and it became more widespread after the large aid cut rallies in March. Following the demonstrations, official hostile rhetoric against Karabakh Armenians reached a point where the government’s human rights ombudsman issued a statement saying “hate speech and discrimination must be eliminated from public discourse”.

Many expect the tensions to escalate ahead of the 2026 parliamentary elections. It is unlikely that refugees will sway the polls. They can vote only after applying for Armenian citizenship and, as of September, just over 16,000 had applied to become citizens. Even if the entire population were eligible and voted as a monolith, they would be a negligible force in an electorate of 1.3 million (based on turnout in the last parliamentary elections). Nonetheless, their arrival to Armenia in 2023, as one report put it, “intensified political insecurities among the ruling elite who feared that the refugees, having lost their homes and livelihoods, might mobilise politically to demand rights or recourse for the loss of their homeland”. Ruling-party officials and their supporters express fear that an alliance of the opposition, refugees and Russia represents a threat to their rule – and, by extension, to the peace process with Azerbaijan.

That, however, is highly unlikely. Beyond their small numbers, the refugees are largely politically apathetic. A poll from late 2024 suggested that refugees supported former Karabakh and Armenian leader Kocharyan over Pashinyan by only two percentage points, though both only scored single-digit support. A full 75 per cent trusted no one. As for Russia, Karabakh Armenians view Moscow as having repeatedly failed to come to their aid. While Russian peacekeepers deployed to Karabakh after the 2020 war, they did nothing to halt successive Azerbaijani advances. By contrast, refugees were grateful to Pashinyan for the initial welcome they received after the exodus of 2023, though the mood has soured. As a Karabakh NGO leader put it: “I tell them [officials], do at least one good thing for Karabakh people, and they will sympathise with you”.

Nonetheless, Pashinyan’s prospective challengers are playing to the refugee population in the run-up to the June 2026 elections. They have criticised him for his handling of the Karabakh crisis, suggesting that Azerbaijan was able to seize back the enclave due to Pashinyan’s falling-out with Russia. They say they would restore amicable ties with Russia, which they contend – against all evidence – would then force Azerbaijan to return Karabakh to Armenian control.

Platform Gap

Though they have little appetite for Armenian organisational politics, many refugees would benefit from an effective organisational voice that could advocate for Karabakh Armenians in Armenia. The closest thing right now is a group called the Council for the Protection of the Rights of the Artsakh People, which is led by figures affiliated with the former de facto NKR authorities and organised the aid cut protests in March. But the Council heads are not especially popular. NKR leaders lost much of their authority among Karabakh Armenians following the exodus from Karabakh in 2023, which many refugees felt was disastrously handled.

Nor do they get along with the Armenian government. Even refugees sympathetic to the NKR leaders understand that they have little leverage with the authorities in Yerevan. The NKR continues to exist in rump form, its former “embassy” in the capital serving as a headquarters, but its members are under pressure from the Armenian authorities. “They closed our accounts. They don’t allow us to use our [NKR] funds in the bank. They are blackmailing us, saying they will take away the building”, a figure close to the NKR leadership said. “They do everything they can to force the [de facto] government to keep silent”.

But if the Council is a less than effective platform, alternatives are starting to take shape. Foreign donors, local NGOs and refugee activists are building a network that can advocate for the rights of refugees and help them navigate the Armenian bureaucracy. Some of the NGOs that relocated from Karabakh are partnering with well-established Armenian ones. Meanwhile, a number of European- and U.S.-funded initiatives are setting up councils or advocacy groups among refugees, helping them liaise with relevant Armenian government agencies. Programs to expand refugee representation are still new, however. None of the refugees interviewed in Masis were aware of such non-governmental efforts.

Dreaming of Home

It is hard to find a refugee who does not express a desire to return to Karabakh, but most also fear doing so as long as Azerbaijan is in control. Azerbaijan says Armenians are welcome back, as long as they accept Azerbaijani citizenship and live under Azerbaijani laws. Baku set up a web portal to allow Karabakh Armenians to start what it calls the “reintegration” process. It has found no takers. None of the refugees interviewed by Crisis Group said they trusted the Azerbaijani authorities to allow them to live in their homes safely, with their rights respected. But for most, if not all, of them, safety and security imply self-rule of the sort they had prior to 2020. “I want to go home”, the leader of a Karabakh women’s NGO said. “But home is not just a box where I live, it is the school where my children will go, the police who will protect me, my language”. Indeed, many said they would go back only if there were some kind of international force separating them from Azerbaijani authorities, a clear non-starter for Baku. The right of return is fundamental to international law, an international aid official said, but the specifics of how return happens “have to be worked out between the two sides”. With Karabakh Armenians unwilling to return to a Karabakh controlled by Azerbaijan, and Baku unwilling to accept anything else, any kind of compromise is for now a distant prospect.

While some in Armenia and the EU have called on Azerbaijan to allow for the return of refugees, the Armenian government is silent on the issue. Soon after the 2020 war, even before the mass exodus that came three years later, Armenia filed suit in the International Court of Justice seeking, among other things, the safe return of Armenians displaced from Karabakh. Yerevan also raised concerns about the rights and security of Armenians in Karabakh early in the peace talks, but then it dropped the subject later in the negotiations. “There was a decision from the Armenian side to remove this”, an Armenian official said. “If we had forced it [the right of return], it is clear we wouldn’t have gotten this far” in the dialogue. One provision of the peace deal with Baku is that, when it is signed, the two states will withdraw international legal claims against the other, including the ICJ case.

Yerevan now is keen to discourage even a hint of what Baku refers to as “revanchism” among Karabakh Armenians. In August, Pashinyan said of the refugees: “I do not consider their ideas about return to be realistic”. The issue, he said, was “a dangerous and harmful topic for the newly born peace”. As a counter to potential claims by Karabakh Armenians, Azerbaijan has advanced ambiguous claims for people it calls “Western Azerbaijanis”, ethnic Azerbaijanis who lived in Armenia until they were forced to flee in the first war between the two sides. “The [Armenian] government is afraid of the ‘Western Azerbaijan’ narrative”, a refugee NGO official said.

The Armenian government’s decision to bury the issue has added to refugees’ resentment.

The Armenian government’s decision to bury the issue has added to refugees’ resentment. Many are angry that the government has not organised a public commemoration related to Armenians’ losses in Karabakh. On the second anniversary of the Azerbaijani offensive that led to the exodus from the enclave, Pashinyan posted a light-hearted message on Facebook ignoring that event and instead featuring a classic Armenian pop song while wishing Armenians a “nice start to the work day”.

Somewhere between nurturing hopes of a reconquest of Nagorno-Karabakh and completely ignoring the desire of its former residents to return may lie actions that could at least help soften the blow of separation that refugees are feeling. Some have proposed organising visits to Karabakh for refugees to see family graves or visit homes and take personal photographs, documents and other belongings left behind as they fled. An Azerbaijani official said Baku is amenable to conversations on that topic, though only after a peace agreement is signed, adding that it would expect similar arrangements for Azerbaijanis who fled Armenia in the first war. Refugees surveyed by Crisis Group were split about the potential for return visits to an Azerbaijan-controlled Karabakh. “I am not going to my home as a tourist”, said the head of a refugee NGO. But Karine was open to the prospect: “I only want our family photo album”.

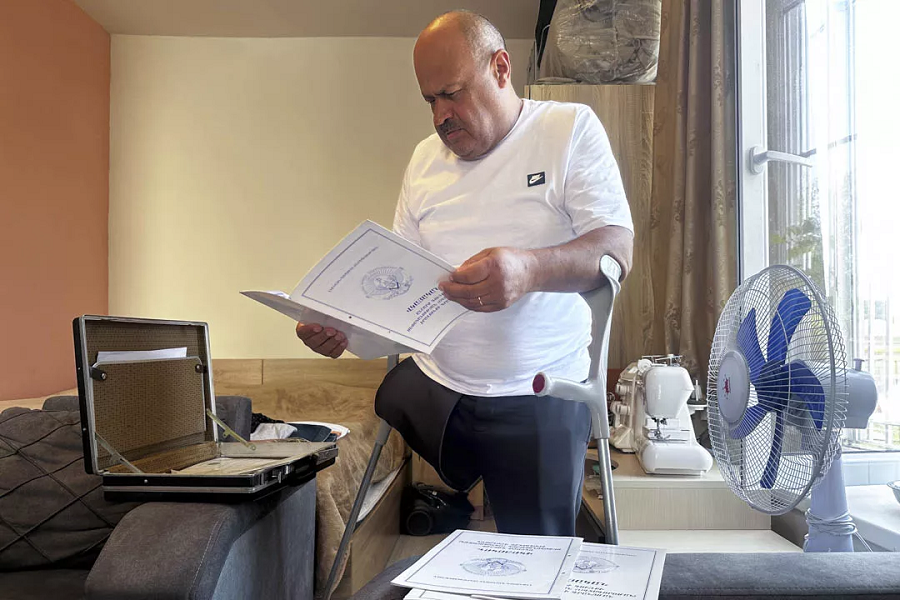

Karlen, a displaced resident from Nagorno-Karabakh, reviews official documents related to property he had in Karabakh. October 2025. Marut Vanyan for CRISIS GROUP

An Uncertain Future

Armenia’s willingness to renounce territorial claims on Karabakh has helped the prospects for peace in the Caucasus, but the process has left former residents of Karabakh feeling stranded. Pashinyan has said he wants Karabakh Armenians to thrive in new homes in Armenia. Yet without more effort to bring refugees into the fold – economically, politically and socially – the displacement may become an unhealed wound.

Refugees and groups advocating for them need to accept that a return to Karabakh under the conditions that they demand – namely, that Azerbaijan relinquish control of the territory – is not realistic. Azerbaijan will not give it up, and Armenia has neither the means nor the desire to take it from the stronger Baku. Moving on from those demands will help focus attention on what can be done to improve the lives of the refugees now and to take initial steps toward what should be a shared future in the region.

For their part, the Armenian government and its allies should step back from what has become a hostile and defensive approach toward the refugees and instead articulate a positive vision for them. “The government should come out and say, ‘We don’t consider you a protest electorate, but a resource for the development of Armenia’”, an Armenian NGO leader said. Armenia’s international partners can encourage better relations between the Armenian government and refugees. For example, as the EU works out benchmarks for Armenia’s deeper integration into the bloc, it could include provisions on abstaining from hate speech against marginalised groups. International partners should also continue to fund, advise and otherwise promote efforts at integration of refugees into Armenian society and politics.

Yerevan should also seek opportunities as talks with Baku progress to explore the potential for refugees to visit homes, graves and other sites they left behind in Karabakh. The time may not be ripe now, given how fresh the wounds are from the conflict. But the grievances that remain from former cycles of displacement by both Armenians and Azerbaijanis should be a lesson that those of Karabakh refugees are unlikely to fade away. Small gestures, if and when diplomatic progress allows for them, could be one step in the journey toward a reconciliation between the two long-time foes, even if it may be the work of generations.

In the main photo: Karine serves coffee in her home in Masis, Armenia, where she lives with her family after being displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023. October 2025. Marut Vanyan for CRISIS GROUP