In the Brussels debates and in national – especially populist – campaigns, a recurring refrain for months has been that “financing Ukraine simply costs too much” for the European Union. The figures, however, tell a different story: the EU is currently paying roughly the same amount as it would cost if Russia actually won the war and took the fight to NATO, according to projections – a scenario where there would be far greater risks.

One of the great advantages of cross-border journalism is that it allows us to illustrate the impact of politics on Europeans’ everyday lives from several perspectives at once. A good example is how differently the media present the financial burden of supporting Ukraine to Irish and Hungarian citizens. While PULSE’s Irish partner, The Journal, debunks with detailed figures the myth that “financing Ukraine has cost Ireland billions of euros”, the line from Hungarian news website Origo is that “spending money on Ukraine is like pouring it into a leaky sack”, a typical snapshot of how government-aligned media target the sensitivities of their audience.

More generally, however, a Europe-wide trend is emerging: more and more politicians are campaigning on the claim that the financial burden of the war in Ukraine is unsustainable. All this is happening at a decisive moment, when Europe must assume full responsibility for financing a war in Ukraine that is slowly approaching the duration of the two world wars, as Washington retreats into the background. This, in turn, severely tests the political deal-making skills of EU leaders, together with the EU’s legal frameworks.

Read also

Who lends Ukraine support?

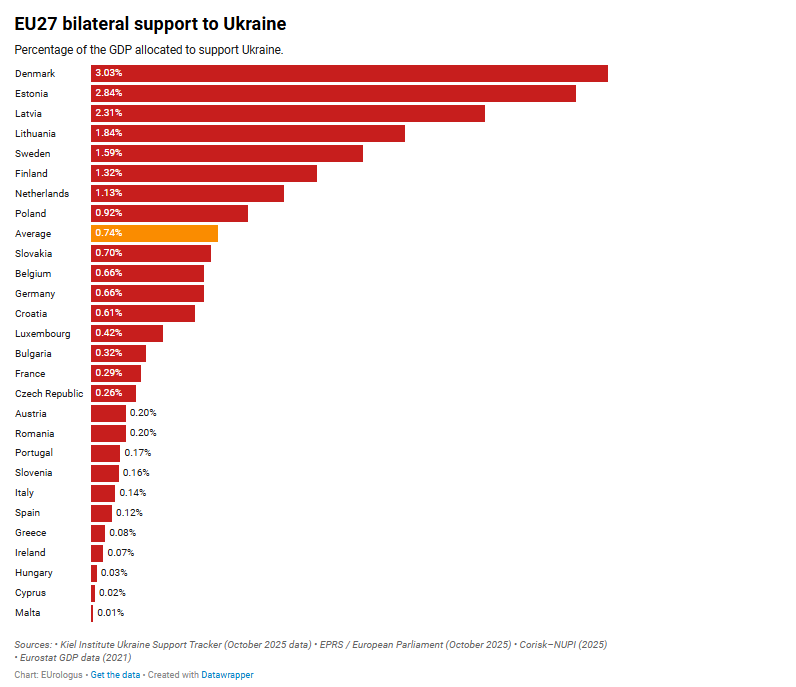

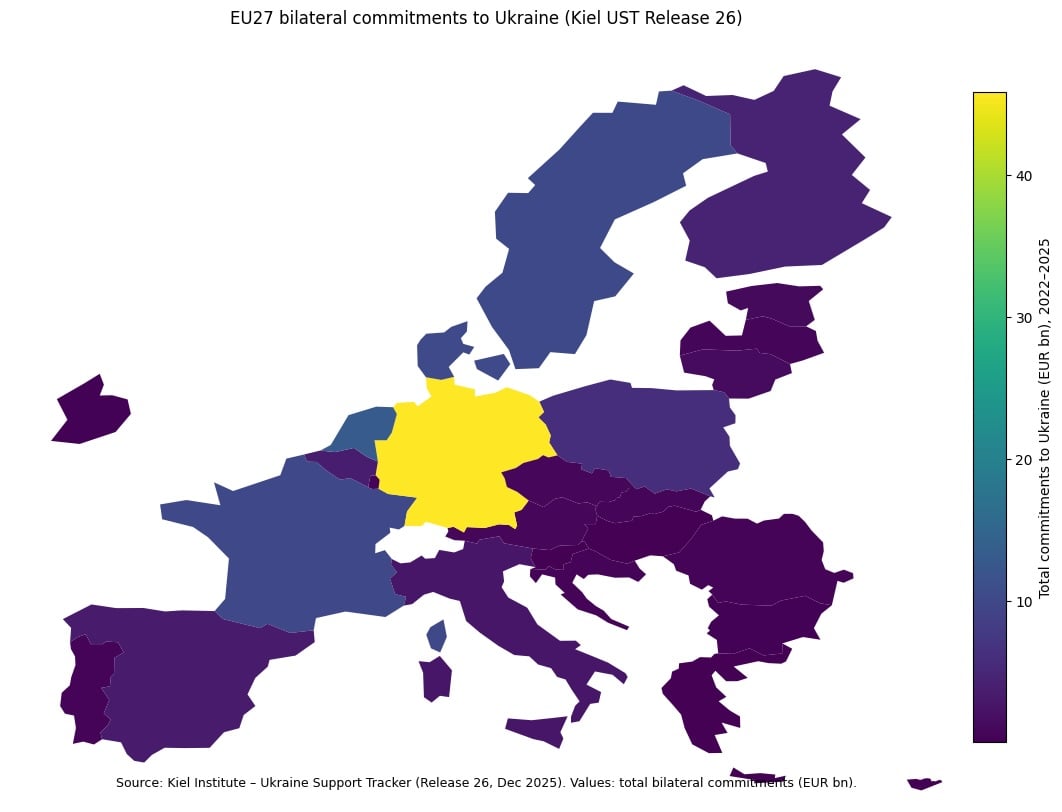

The up-to-date data from the Kiel Institute’s Ukraine Support Tracker shows that Hungary spends relatively little on supporting Ukraine, despite – or perhaps precisely because of – the proximity of the war in the neighbouring country. This contrasts sharply with the comparatively less affluent Baltic states and the Nordics, which shoulder the greatest burden relative to their GDP. Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia are also exceptionally generous in the “middle band”, while in absolute terms Germany and France provide the most support.

Among international lenders and donors, however, there is broad agreement about the urgency of guaranteeing continued support for Ukraine. In its statement of 26 November 2025, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) does not mince its words:

“Prompt action by donors is indispensable to avoid liquidity strains.”

The IMF also stresses that Ukraine’s fiscal and external financing needs are large, and that risks are “exceptionally high” due to the duration and intensity of the war and fluctuations in donor support. Meanwhile, the World Bank provides a concrete figure, estimating Ukraine’s external financing needs for 2025 at €37 billion – in other words, securing financing from early 2026 onward is urgent.

Fresh figures from the Kiel Institute also sound the alarm over the drastic decline in military and defence support in 2025. Ukraine is facing one of the years with the fewest new aid decisions since the outbreak of the war in 2022. Europe has allocated only about €4.2 billion in new military aid to Ukraine – far too little to offset the halt in US support, warns the Kiel Institute’s analysis. At the same time, disparities within Europe have widened. France, Germany and the United Kingdom have significantly increased their allocations, but in relative terms they still lag behind the Nordic countries. By contrast, Italy and Spain have contributed only minimally.

It is also worth noting that Germany provides the most funding for air-defence systems and tanks, while Poland, the Czech Republic and the Baltic states have delivered the largest quantities of heavy weapons.

As for Ireland, earlier this month Taoiseach Micheál Martin announced an additional €125 million in financial support for Ukraine as part of a new roadmap for partnership with Ireland to cover the next five years.

That roadmap includes the allocation of an additional €100 million in non-lethal military support, with another €100 million having previously been announced, and €25 million to support the restoration and protection of Ukrainian energy infrastructure.

Some €35.4 million in humanitarian and stabilisation supports had already been announced by the Irish government this year.

Elsewhere, refugee costs in Europe weigh particularly heavily on Germany, Poland, Romania and the Czech Republic.

How much does Ukraine cost the EU? What the numbers show

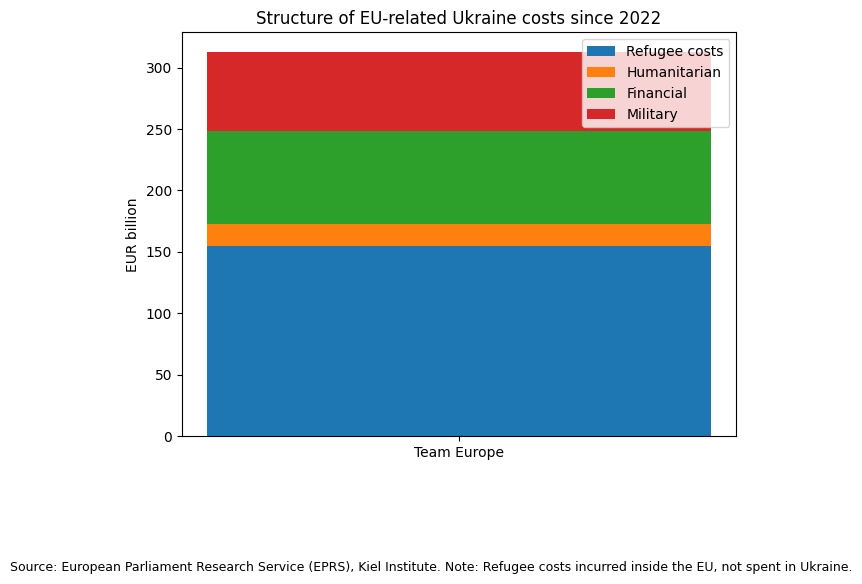

According to an October 2025 overview by the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS), EU institutions and the 27 member states together, as “Team Europe”, have mobilised around €177.5 billion in financial, military and humanitarian support for Ukraine since February 2022.

This includes macro-financial assistance and the €50 billion Ukraine Facility for 2024-2027, of which €38.27 billion is direct budget support, mainly through concessional loans. Added to this is military assistance, which the EPRS estimates at around €63-65 billion when including member-state deliveries and payments from the European Peace Facility (EPF).

Finally, refugee support is the item that the public rarely associates directly with Ukraine, yet based on data from the Kiel Institute’s Ukraine Support Tracker, the EPRS estimates EU member states’ refugee-related expenditures at around €155 billion between early 2022 and August 2025.

If everything is added together – EU budget programmes, military aid and refugee costs – Ukraine’s “price tag” for the EU so far is in the order of €330 billion over 3.5 years. On an annual basis this is around €90-100 billion, while the EU-27’s GDP in 2024 was well above €15,000 billion – meaning the bill amounts to roughly 0.6–0.7 percentage points of economic output per year.

EIB and EBRD: the EU’s “development wartime economy”

Beyond classic budgetary items, it should not be forgotten that EU financial institutions are also key players in financing Ukraine. According to a July 2025 statement by the European Investment Bank (EIB) Group, since the start of the Russian invasion it has mobilised €3.6 billion in support and loans for Ukraine – mainly for energy infrastructure, transport and SME financing.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is Ukraine’s largest institutional investor during the war: at the 2025 Ukraine Recovery Conference in Rome, it reported wartime financing reaching €7.6 billion and aims to maintain an annual level of €1.5-2 billion.

These figures do not represent “extra luxury investments” but primarily power plants, bridges, urban district-heating systems, border crossings, and the survival of small and medium-sized enterprises – in other words, everything without which a frontline country would quickly become a permanently unstable, collapsing neighbour.

Europe vs. the US: who really pays for Ukraine’s war?

Amid the transatlantic “who pays more?” debate, latest data shows that earlier this year Europe moved from being a passenger to becoming the main financier. According to the Kiel Institute, since 2022 EU institutions and member states together have committed around €165.7 billion in support to Ukraine, while the United States has provided about €130.6 billion.

The EPRS also highlights that by 2025 Team Europe had overtaken the United States in total allocated financial, humanitarian and military support.

In military equipment, EU member states have also allocated slightly more to Ukraine this year than Washington: €65.1 billion compared with €64.6 billion from the US, alongside a further €32.8 billion in European pledges.

The picture is more nuanced, however, as a larger share of US support consists of grants, while around 75% of EU financing takes the form of concessional loans with long grace periods and interest subsidies. Admittedly, this means lower immediate costs, but the EU assumes greater long-term financial risk – partly based on the expectation that the loans will ultimately be repaid from Russian assets or “war reparations loans”.

Which would cost more: a Ukrainian victory or a Russian breakthrough?

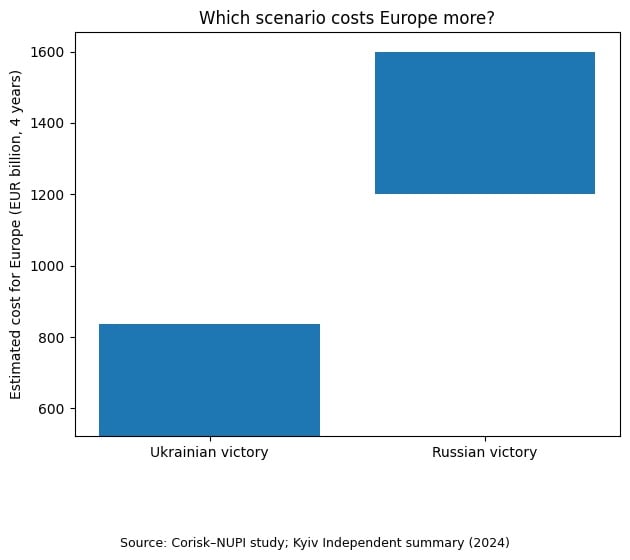

Paradoxically, the strongest argument against the claim that “financing Ukraine is too expensive” is to outline how costly it would be not to pay.

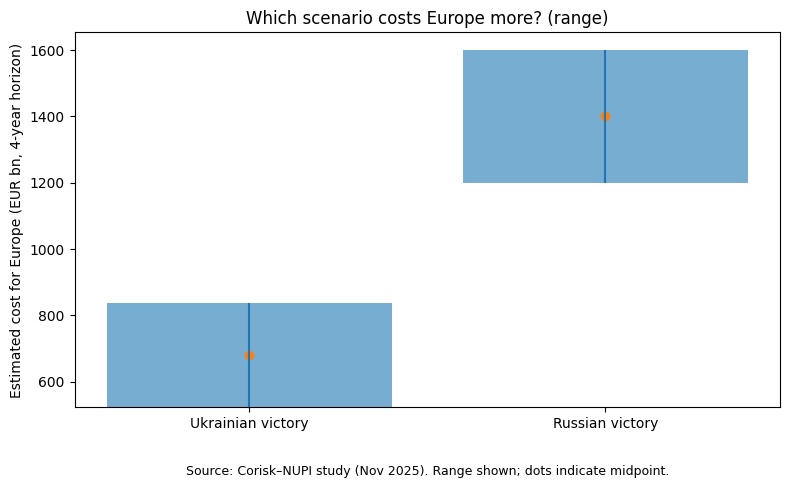

A recent study by the Norwegian, civil-funded analytical firm Corisk and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) provides a clear framework by comparing two scenarios:

Scenario 1 – Russian (partial) victory: Moscow pushes the front westward, Ukraine is forced to accept a “bad peace” and loses up to half of its territory. According to the study, this would impose €524–952 billion in refugee and social costs on Europe over four years, plus additional defence spending, bringing the total bill to €1.2-1.6 trillion.

Scenario 2 – Ukrainian victory: Europe arms Ukraine (1,500-2,500 tanks, 2,000-3,000 artillery systems, up to 8 million drones, modern air defence), enabling it to push back Russian forces and force the Kremlin into a favourable peace. Researchers estimate the cost at €522–838 billion over four years – roughly half of what Europe would pay in the event of a Russian victory.

The study also assumes a reduced role for the United States, meaning that the bulk of the burden – as today – would fall on Europe.

How much would it cost if Russia attacked a NATO member?

There is no direct, official EU calculation of the cost of an actual NATO war, but there are approximate estimates of what European defence would require even in the event of a US withdrawal.

According to a 2025 analysis by the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel, if Europe had to deter Russia without the United States, it would need at least 300,000 additional troops and around €250 billion in extra defence spending annually in the coming years.

According to the Norwegian study cited above, additional defence spending to reinforce NATO’s eastern flank in the event of a Russian war against NATO would raise Europe’s total costs under Scenario 1 to €1.2–1.6 trillion.

This alone already exceeds what the EU currently spends in total on supporting Ukraine – and this calculation does not even include potential infrastructure destruction in the Baltic or Scandinavian theatres, nor new waves of refugees.

This article was written as part of a cross-border European journalistic collaboration within the framework of the EU NEIGHBOURS east project.

Author: György Folk (EUrologus / HVG, Brussels)