By Varouj Pogharian

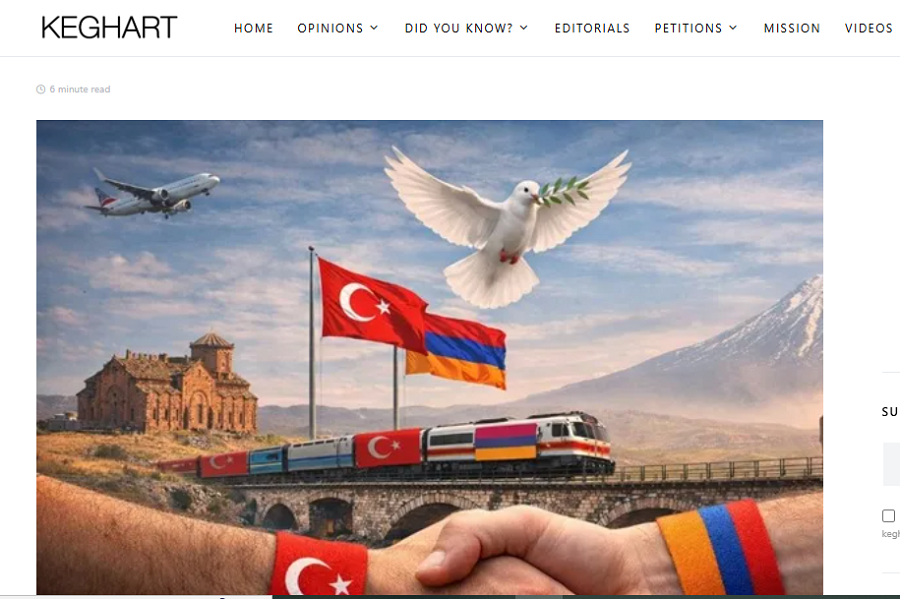

How We Stopped Treating the Future as a Betrayal of the Past

For most of the last century, “reconciliation” has been treated as a suspect word in the Turkish–Armenian context. It was something elites whispered about in conference rooms, but not something ordinary people trusted. To most Armenians, it sounded like surrender—an invitation to forget the dead in exchange for vague promises of trade and travel. To many Turks, it sounded like an accusation—an opening wedge that would end in blame, shame, and endless legal claims. Between these two fears, the word became radioactive, and every major attempt at reconciliation failed badly. Each failure reinforced the idea that reconciliation itself was naive at best, dishonest at worst.

We are now in January 2026 and something has quietly, practically, and irreversibly changed. Reconciliation is no longer a dirty word—not because history has been settled between Armenians and Turks, but because agency has returned.

Read also

The Original Sin: TARC and the Fear of Premature Peace

The Turkish Armenian Reconciliation Commission (TARC), launched in July 2001, was the first serious post–Cold War attempt to break the ice. It was a classic “Track Two” initiative: unofficial, elite-driven, discreet, and heavily reliant on Western sponsorship—especially from the U.S. State Department. The logic was simple. Since Ankara and Yerevan had no diplomatic relations and a sealed border, civil society would have to go first.

On paper, TARC was bold. It tackled trade, culture, tourism—and most dangerously—history. By commissioning the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) to evaluate whether the events of 1915 constituted genocide under international law, TARC stepped directly into a minefield.

The ICTJ’s conclusion was devastating and clarifying at the same time: yes, the massacres met the legal definition of genocide; no, the Genocide Convention could not be applied retroactively for prosecutions or reparations.

In theory, this should have lowered the temperature. In practice, it blew the commission apart.

For Armenians, reconciliation without acknowledgment felt empty. For Turks, acknowledgment felt toxic. Both sides retreated to their corners. Diaspora Armenians condemned TARC as a smokescreen designed to derail genocide recognition by foreign parliaments. Turkish nationalists framed it as capitulation to foreign pressure. When U.S. attention shifted after September 11 toward Iraq and the necessity for Turkey’s strategic cooperation, TARC lost its last scaffolding.

The lesson many people took was the wrong one: reconciliation doesn’t work. The real lesson was harsher and more precise: reconciliation without legitimacy collapses.

Zurich: The Grand Bargain That Broke Under Its Own Weight

The 2009 Zurich Protocols tried again—this time at the state level. No more quiet commissions. A treaty was hoped to be signed under chandeliers, brokered by Switzerland, and blessed by Washington, Moscow, and Paris. The ambition was enormous: diplomatic recognition, border opening, economic cooperation, and a historical sub-commission

It was everything at once. And that was the problem.

The protocols fell into what might be called a “triple trap.” First, Nagorno-Karabakh hovered like an unspoken ghost. Although deliberately excluded from the text, it dominated reality. Azerbaijan viewed normalization as betrayal. Turkey, dependent on Azerbaijani energy and solidarity, folded almost immediately, reintroducing Karabakh as a precondition after the signing. Armenia saw this as bad faith. Trust evaporated.

Second, the historical commission enraged nearly everyone. Armenians rejected the idea that genocide required re-examination. Turks feared that even participating implied eventual admission of guilt. The commission satisfied no one.

Third, domestic law finished the job. Armenia’s Constitutional Court, while approving the protocols, clarified that nothing in them could undermine genocide recognition. Turkey seized on this as proof that Armenia was acting in bad faith. The documents sat in parliamentary drawers until Armenia finally declared them null and void in 2018.

Again, reconciliation was blamed. The real failure lay in the belief that history, borders, identity, and geopolitics could be resolved in one ceremonial stroke.

The End of the Grand Bargain Illusion

The current normalization process—still fragile, still contested—looks nothing like Zurich. There are no protocols. No grand commissions. No claims of “historic breakthroughs.” Instead, there are e-visas.

Russian border guards have begun to step back on the Armenian side, quietly and without ceremony. Third-country nationals are already permitted to cross at the Margara–Alican land border. Beginning January 1, 2026, holders of diplomatic and special passports are expected to move between Turkey and Armenia under simplified e-visa procedures. And, Turkey’s flagship carrier is set to add flights to Yerevan in March, supplementing existing Pegasus Airlines service from Istanbul. None of this has made big headlines. That is precisely why it is working.

The driving force is transit: railways, roads, and logistics hubs. The TRIPP project—the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity—has an awkward name, but its logic is hardnosed. Restore Soviet-era rail lines. Connect Turkey to Armenia, Armenia to Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan to Central Asia. Let goods move. People will follow.

As the Karabagh conflict settles into a negotiated framework, Turkey’s long-held justification for sealing the border—solidarity with Azerbaijan—has eroded.

Unexpected Teachers: Ana Kasparian and Cenk Uygur

The collaboration between Ana Kasparian, an Armenian American, and Cenk Uygur, a Turkish American, on The Young Turks TV program is one of the most instructive examples of reconciliation in practice. The two didn’t erase their differences. They publicly navigated their complex personal and national histories in dialogue and debate, and grew. Their shared values outweighed their inherited national scripts.

This partnership survived because of one crucial step: Cenk’s public recognition of the Armenian Genocide. The acknowledgment was not performative. It was costly as it alienated parts of his own community. Yet, it allowed Ana to feel seen and respected, and punctured a central myth: that reconciliation requires forgetting. It doesn’t. It requires agency—the refusal to let inherited hatred be the sole author of the present.

Grassroots: Where Reconciliation Actually Lives

Reconciliation is no longer waiting for parliaments. It’s happening in Gyumri and Kars–in oral history projects, railway feasibility studies, and tourism workshops. These initiatives understand something earlier efforts missed: legitimacy grows from usefulness. When Armenians and Turks collaborate on restoring a bridge, training tourist guides, or planning passenger stops along the Kars–Gyumri railway, reconciliation stops being symbolic and starts being practical.

For much of the last century, the Armenian Diaspora acted as a necessary guardian of memory. That role is not obsolete. But it is incomplete. In 2026, the Diaspora has leverage not only through lobbying efforts, but through investment and participation—by financing a warehouse near the Gyumri rail hub or funding a fellowship that places an Armenian engineer in Kars and a Turkish doctor in Yerevan.

These acts won’t dilute justice. They anchor it in reality.

Why Reconciliation Is No Longer a Dirty Word

Reconciliation failed when it asked people to leap before the ground below was visible. It failed when it tried to solve everything at once. It failed when it was imposed.

What is happening now is different. History has not been resolved—but it has been acknowledged by enough individuals to loosen its chokehold. The past is not forgotten—but the future is no longer held hostage to it. Borders are not fully open—but they are no longer just speculative.

Reconciliation, stripped of its euphemisms, is simply this: refusing to outsource the future to the worst moment of the past. Reconciliation is no longer radical. It is practical. And at last, it seems to be working.

Elderly villagers on the borders interviewed by journalists often remember a time before borders hardened, with stories of shared meals, borrowed tools, and mutual protection. These narratives don’t erase 1915. They complicate the lie that coexistence is impossible.

The coming Armenian elections will test the new shifts. Fear remains potent. Disinformation travels faster than a jet. But the choice before us is clearer than it has ever been: frozen righteousness or sovereign engagement.